TikTok Users Struggle to Access App after Kyrgyzstan Announces Restrictions

Kyrgyzstan is restricting access to TikTok. The Ministry of Digital Development sent a letter to internet providers, asking them to block the TikTok social media platform, local media has reported. The ministry cited the network´s failure to comply with a law designed to “prevent harm to the health of children,...

The Taliban and its Neighbors: An Outsider’s Perspective

This is part two of a piece of which part one was published here. The topic of a regional approach to solving Afghanistan's problems is increasingly being discussed in various expert and diplomatic circles. The International Crisis Group (ICG), a reputable think tank whose opinion is extremely interesting as part...

Kazakh News Publisher Says New Media Law Does Little for National Press

Kazakhstan's new law "On Mass Media," recently passed by its lower house of parliament (the Majilis), has agitated the country's reporters. In an interview with The Times of Central Asia, Dzhanibek Suleyev, the publisher of several news sites, remonstrates that the law should have been more supportive of the national press. An...

Development of Kazakhstan’s Cinematography: An Inside Look – An Interview with Kazakh Actor, Abay Kazbayev, on Kazakhstan’s Film Industry and its Prospects for Development

Kazakhstan's film industry is attracting more and more attention globally, and many talented actors are contributing to its development. One such theater and film actor is Abay Kazbayev, who agreed to share his experience and vision of the industry. How did you start in the industry? I have...

Authorities Find Secret Tunnel Connecting Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan

Another underground passage has been found in the Jalal-Abad region of Kyrgyzstan, which was being used to illegally transport both people and contraband goods into neighboring Uzbekistan. The suspects involved have been arrested. That's according to a report from news outlet, Kaktus, which references information from the press service of...

Innovating in Uzbekistan: Council Aims to Nurture Young Scientists

TASHKENT, Uzbekistan - Uzbekistan has this to say to any young Uzbek citizen interested in science: Step up and collaborate. Uzbekistan’s Council of Young Scientists, or CYS, is seeking to expand the ranks of fledgling scientists, overseeing financial and other support as well as programs to attract researchers. The group,...

Tajikistan Takes Steps to Punish Sorcerers and Fortune-Tellers

The authorities in Tajikistan plan to introduce punishment in the form of compulsory labor for up to six months for those involved in fortune-telling, sorcery, or witchcraft. "On the territory of the Republic of Tajikistan, inspection and preventive work is continuing to prevent violations related to non-compliance with the requirements...

Market Capitalization of the Kyrgyz Stock Exchange Reaches Record Level

In a short period of time, the Kyrgyz Stock Exchange (KSE) has launched various financial instruments: a government securities market, a precious metals market, other commodities instruments, and a sustainable development sector, KSE President Medet Nazaraliev explained at a meeting with representatives of the business community. The head of the...

Kazakhstan Debates Foreign Media Accreditation

2 hours ago

Carlsberg Expands Production in Kazakhstan

5 hours ago

The Taliban and its Neighbors: An Outsider’s Perspective

This is part two of a piece of which part one was published here. The topic of a regional approach to solving Afghanistan's problems is increasingly being discussed in various expert and diplomatic circles. The International Crisis Group (ICG), a reputable think tank whose opinion is extremely interesting as part...

Uzbekistan: From Silk Roads to New Horizons

Cradled by the embrace of the Syr Darya and Amu Darya Rivers, Uzbekistan boasts a rich tapestry woven from the threads of history. Being home to trade hubs like Samarkand and Bukhara, this land has been at the center of cultural exchange for over a millennia. From the Turkic-Mongol tribes...

The New Silk Road

In light of the current geopolitical situation in the world, many countries are puzzled by the search for new alternative transport routes. One of these is the Trans-Caspian International Transport Route (TITR), which runs through China, Kazakhstan, the Caspian Sea, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and further to Turkey and European countries. New...

Taliban and its Neighbors: A Regional Format for Overcoming Challenges in Afghanistan and Beyond

The process of making Afghanistan an independent economic entity that can work constructively within globally accepted economic standards and formats will require addressing pressing security issues as well as strengthening regional partnerships and cooperation. In the long term, this will not only benefit the people of Afghanistan but also its...

How India is Becoming a Robust Soft Power in Central Asia

The middle-income trap, a pressing issue that has led to the stagnation of many successful developing economies, demands immediate attention. This trap, which occurs when a middle-income country can no longer compete internationally in standardized, labor-intensive goods due to relatively high wages, is a result of various factors, including countries...

The Priority of Maintaining a United and Stable Afghanistan

The issue of inter-ethnic relations in Afghanistan affects not only the country itself but also its surrounding region. Recent history has placed a heightened importance on the “nation” question in Afghanistan in terms of the country’s political and social stability. Since regaining power in 2021, the de facto Taliban authorities...

The Middle Corridor: How Kazakhstan is Carving its Niche in Europe-Asia Transport

In the aftermath of the pandemic and amid rising geopolitical tensions and sanctions – leading to the breakdown of traditional shipping and logistics chains – the need to develop new, alternative routes for trade has gained particular importance. One such route is the Middle Corridor, or Trans-Caspian International Transport Route,...

One Step Forward, Two Steps Back: the EU’s Indecisive Strategy Towards Eurasia

Times of Central Asia Editorial Marking the next chapter in the geopolitical re-balancing competition between Russia and the West, the European Parliament (EP) on 13 March passed a resolution on deepening ties between the EU and Armenia. The document puts forth the possibility of granting Armenia candidate status for EU...

Central Asia Can Help Bring Afghanistan into the International Fold

Afghanistan's situation remains deeply troubling, reflecting a complex history of conflict and political instability that has severely impacted its social and economic fabric. The Soviet Union's invasion 45 years ago, followed by the Taliban's rise to power in 1996 and the U.S. involvement after the September 2001 terrorist attacks linked...

Creation of Kazakhstan–Azerbaijan “Supreme Interstate Council” Marks New Era of Cooperation

Diplomatic relations between Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan have developed dynamically since they were first established in August 1992, and have increased over the past 20 years, and grown especially since 2017. Over the last decade, the number of high-level visits in both directions have been rising to the point where they...

Letting Women Lead: Bridging the Finance Gap for Women-Led Businesses

Opinion by Hela Cheikhrouhou, IFC Regional Vice President, Middle East, Central Asia, Türkiye, Afghanistan, and Pakistan I get to meet many courageous women in my work for IFC in Southwest and Central Asia. [1] I’ve witnessed the seemingly insurmountable challenges they encounter every day. I’ve seen the unyielding resolve of...

Religion in the Cities of Kazakhstan – Opinion by Gulmira Ileuova

The research discussed in this article was conducted in July-August 2023 by the Strategy Center for Sociological and Political Studies Public Foundation in collaboration with the office of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation in Central Asia. A total of 1,604 people were surveyed in six cities. Since the goal of the...

Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan Enhance Allied Relations

On April 19 Astana hosted the sixth meeting of the Supreme Interstate Council of Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan. Chaired by Kazakh President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev and Kyrgyz President Sadyr Japarov, discussions focused on the development of bilateral cooperation in economy, trade, investment, and agriculture, in addition to joint projects regarding transport, water...

Kazakh, Chinese and Russian Companies Unite on Polyethylene Production Plant

On April 19, a meeting was held between Magzum Mirzagaliyev, Chairman of the Board of KazMunayGas, Zhao Dong, President of the China Petrochemical Corporation (SINOPEC), and Mikhail Karisalov, Chairman of the Board of Russia’s SIBUR LLC. In the presence of the Prime Minister of Kazakhstan Olzhas Bektenov, the parties signed...

Chinese Investors Plan to Build Solar Power Plant in Tashkent Region

Chinese investors have agreed to implement more major projects in Uzbekistan, according to statements made following the visit of a trade delegation from China to Uzbekistan's Tashkent region. Chinese businesses intend to invest $2 billion in the construction of a solar power plant in Ahangaran, $25 million in providing food...

Poor-Quality Gasoline Refused by Taliban Doesn’t Belong to Uzbekistan

The Customs Committee of Uzbekistan denied that gasoline returned by the Taliban due to its poor quality in fact belongs to Uzbekistan, according to a post on the committee's Telegram channel. The Times of Central Asia has reported that the Taliban returned 120,000 liters of gasoline imported via the Hayraton...

USAID Launches $18 Million Program to Boost Economic Growth in Tajikistan

On 18 April, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) launched a new initiative to support long-term economic opportunities in Tajikistan. Running for five years at a cost of $18 million, Employment and Enterprise Development Activity (EEDA) will partner local firms to improve productivity in the fields of textiles,...

Tajikistan and Uzbekistan Sign Allied Relations Treaty

On April 18, Shavkat Mirziyoyev, President of Uzbekistan met Emomali Rahmon, President of Tajikistan in Dushanbe, where the two leaders signed a Treaty on Allied Relations between their countries. Referring to Tajikistan as Uzbekistan’s closest, most reliable, and time-tested strategic partner, Mirziyoyev announced, “The fraternal Uzbek and Tajik peoples are...

Kazakhstan Increases Amount of Claim Against Western Oil Companies to $150 Billion

Kazakhstan is demanding compensation for lost profits from the operating consortium of the Kashagan oil field, North Caspian Operating Co (NCOC). Arbitration claims made by Kazakhstan have grown to $150 billion, Bloomberg reports, citing people familiar with the story. An additional claim concerns $138 billion of lost profits stemming from...

Uzbekistan Planning to Abandon State Regulation of Coal Prices

A decision to end Uzbekistan's price caps on coal has been made against the background of rising costs for electricity. To date, hard coal in the country is a social commodity, which is sold to the population at fixed prices. Currently, coal is sold under direct contracts to the population,...

Kazakhstan Debates Foreign Media Accreditation

Following their second reading, the Majilis (lower chamber of parliament) of the Republic of Kazakhstan has adopted the bills "On Mass Media" and "On Amendments and Additions to Certain Legislative Acts of the Republic of Kazakhstan in the Field of Mass Media," sending them to the Senate for consideration. The...

Kazakh News Publisher Says New Media Law Does Little for National Press

Kazakhstan's new law "On Mass Media," recently passed by its lower house of parliament (the Majilis), has agitated the country's reporters. In an interview with The Times of Central Asia, Dzhanibek Suleyev, the publisher of several news sites, remonstrates that the law should have been more supportive of the national press. An...

Low-Income Kyrgyz Citizens Offered Financial Literacy Training

Kyrgyzstan's Ministry of Labor, Social Security and Migration has begun to provide training in financial literacy for low-income citizens from all over the country. Those wishing to participate in the state program known as "Social Contract" were offered free training on the basics of entrepreneurship, marketing and financial literacy. At...

Uzbekistan to Raise Energy Prices for First Time in Five Years

Electricity and natural gas tariffs in Uzbekistan will increase from May 1, and social consumption quotas will also be established. The price increase will be the first since August 2019. The quota for electricity use was defined up to 200 kWh per month, for gas -- from March to October...

No Lessons Being Learned From Kazakh Floods, Says Political Analyst

Kazakhstan has been prone to flooding before, but the 2024 Kazakh floods have added a catastrophic page to the chronicles. Political analyst Marat Shibutov tells The Times of Central Asia that only extremely tough measures can motivate ministers and akims (local government executive) to actually work on flood prevention. ...

State Mortgages in Kyrgyzstan Can Now Be Obtained Without Credit History

On April 15, a law introducing a mechanism called "Shared Housing Construction" within the framework of the program, "My House 2021-2026" came into force in Kyrgyzstan. The program, as defined by the State Mortgage Company (SMC) of Kyrgyzstan, is available to all citizens. According to authorities, Kyrgyz citizens should be...

Open Society to Close its Foundation in Kyrgyzstan, Citing Law on Foreign-Funded NGOs

The Open Society Foundations said it will close its national foundation in Kyrgyzstan after the country’s parliament passed a new law that tightens control over non-governmental groups that receive foreign funding. Open Society, which was founded by billionaire investor and philanthropist George Soros, said Monday that the law“imposes restrictive, broad,...

Uzbekistan Proposes Ban on E-Cigarettes

Uzbekistan is drafting a law banning the import, sale and production of electronic cigarettes and tobacco heating systems. The bill has been published on the regulation.gov.uz portal and its discussion will last until April 18, The Times of Central Asia has learned. The draft law mentions that over the past...

Kazakhstan Debates Foreign Media Accreditation

Following their second reading, the Majilis (lower chamber of parliament) of the Republic of Kazakhstan has adopted the bills "On Mass Media" and "On Amendments and Additions to Certain Legislative Acts of the Republic of Kazakhstan in the Field of Mass Media," sending them to the Senate for consideration. The...

Kazakh, Chinese and Russian Companies Unite on Polyethylene Production Plant

On April 19, a meeting was held between Magzum Mirzagaliyev, Chairman of the Board of KazMunayGas, Zhao Dong, President of the China Petrochemical Corporation (SINOPEC), and Mikhail Karisalov, Chairman of the Board of Russia’s SIBUR LLC. In the presence of the Prime Minister of Kazakhstan Olzhas Bektenov, the parties signed...

The Taliban and its Neighbors: An Outsider’s Perspective

This is part two of a piece of which part one was published here. The topic of a regional approach to solving Afghanistan's problems is increasingly being discussed in various expert and diplomatic circles. The International Crisis Group (ICG), a reputable think tank whose opinion is extremely interesting as part...

Carlsberg Expands Production in Kazakhstan

Kazakh Invest has announced that Danish company Carlsberg is to open a new factory in Almaty to produce non-alcoholic beverages worth $50 million. In preparation of its launch, Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs of Kazakhstan, Nazira Nurbayeva, Chairman of Kazakh Invest, Yerzhan Yelekeyev, and First Vice President for Central and...

Uzbekistan Planning to Abandon State Regulation of Coal Prices

A decision to end Uzbekistan's price caps on coal has been made against the background of rising costs for electricity. To date, hard coal in the country is a social commodity, which is sold to the population at fixed prices. Currently, coal is sold under direct contracts to the population,...

CSTO Says It’s Satisfied With Negotiations on Kyrgyz-Tajik Border Demarcation

The Secretary General of the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CTSO), Imangali Tasmagambetov, said in an interview with Tajik media that Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan are managing to peacefully resolve their border conflict. "The will of the political leadership of the two countries made it possible not only to start and successfully...

Air Travel Between Tajikistan and Russia Rebounding After Terrorist Attack

Passenger traffic on flights between Tajikistan and Russia decreased after the terrorist attack at Crocus City Hall near Moscow on March 22, which Tajik members of the Islamic State (IS) are suspected of perpetrating. But the news site Avesta reports that the flow of passengers between the two countries is...

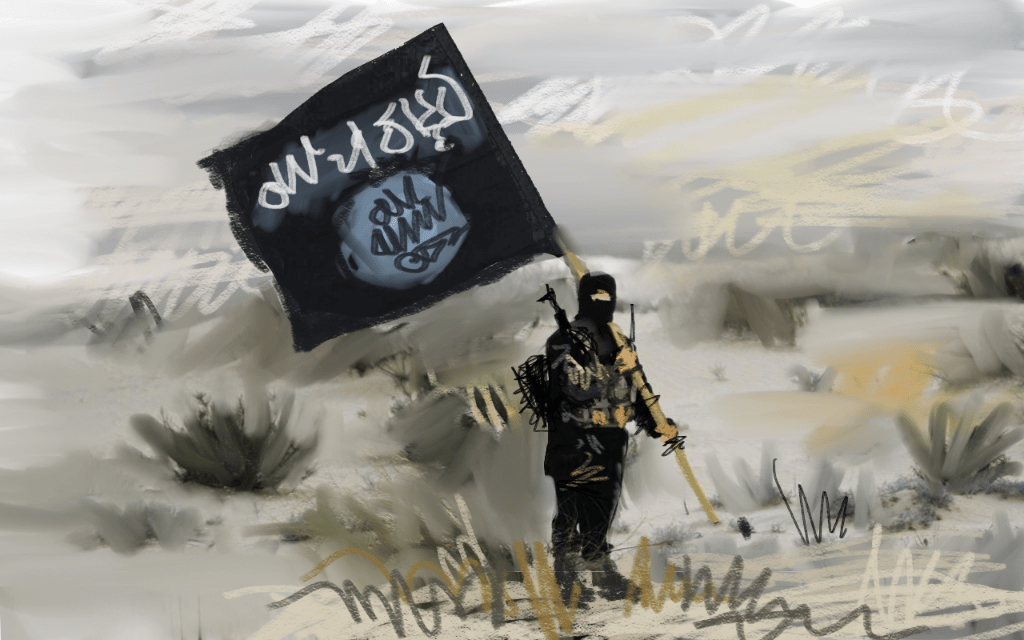

Islamic State – Khorasan Province: An Element of Geopolitical Rivalry?

In the aftermath of the terrorist attack in Moscow, the media has once again been saturated with discussions about the terrorist group Islamic State – Khorasan Province (ISKP), also known as ISIS-Khorasan and “Wilayat Khorasan.” At this point, most of the coverage has focused on the Afghan wing of Islamic...

TikTok Users Struggle to Access App after Kyrgyzstan Announces Restrictions

Kyrgyzstan is restricting access to TikTok. The Ministry of Digital Development sent a letter to internet providers, asking them to block the TikTok social media platform, local media has reported. The ministry cited the network´s failure to comply with a law designed to “prevent harm to the health of children,...

Kazakh News Publisher Says New Media Law Does Little for National Press

Kazakhstan's new law "On Mass Media," recently passed by its lower house of parliament (the Majilis), has agitated the country's reporters. In an interview with The Times of Central Asia, Dzhanibek Suleyev, the publisher of several news sites, remonstrates that the law should have been more supportive of the national press. An...

Development of Kazakhstan’s Cinematography: An Inside Look – An Interview with Kazakh Actor, Abay Kazbayev, on Kazakhstan’s Film Industry and its Prospects for Development

Kazakhstan's film industry is attracting more and more attention globally, and many talented actors are contributing to its development. One such theater and film actor is Abay Kazbayev, who agreed to share his experience and vision of the industry. How did you start in the industry? I have...

Authorities Find Secret Tunnel Connecting Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan

Another underground passage has been found in the Jalal-Abad region of Kyrgyzstan, which was being used to illegally transport both people and contraband goods into neighboring Uzbekistan. The suspects involved have been arrested. That's according to a report from news outlet, Kaktus, which references information from the press service of...

Innovating in Uzbekistan: Council Aims to Nurture Young Scientists

TASHKENT, Uzbekistan - Uzbekistan has this to say to any young Uzbek citizen interested in science: Step up and collaborate. Uzbekistan’s Council of Young Scientists, or CYS, is seeking to expand the ranks of fledgling scientists, overseeing financial and other support as well as programs to attract researchers. The group,...

Tajikistan Takes Steps to Punish Sorcerers and Fortune-Tellers

The authorities in Tajikistan plan to introduce punishment in the form of compulsory labor for up to six months for those involved in fortune-telling, sorcery, or witchcraft. "On the territory of the Republic of Tajikistan, inspection and preventive work is continuing to prevent violations related to non-compliance with the requirements...

Kyrgyz Climber in Nepal Sets Sights on Three of the World’s Highest Peaks

The head of Kyrgyzstan’s mountaineering federation is in Nepal, preparing to climb three of the world’s highest peaks in the next few months. First up for Eduard Kubatov is the Himalayan mountain of Lhotse. Next is Makalu. Both are more than 8,000 meters high. Three years ago, Kubatov unfurled the...

EU Project SCAFFOLD Set to Empower Central Asian Educators

Over 250 educators from five Central Asian countries are currently participating in training events organized by the European Union in Astana, Kazakhstan. Running from 15 – 19 April, the event organized by the European Training Foundation (ETF) in partnership with the Delegation of the European Union to Kazakhstan, and the...

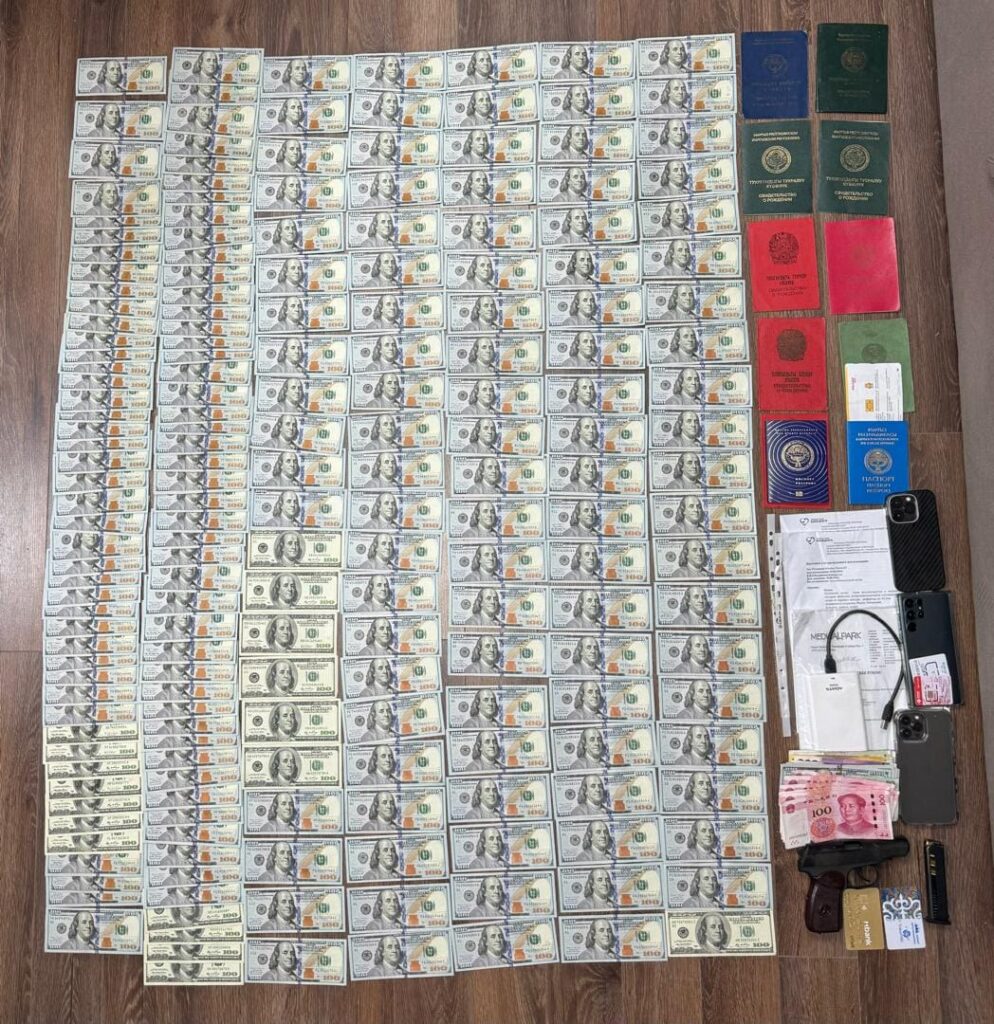

Traffickers of Human Organs Detained in Kyrgyzstan

The State Committee for National Security (SCNS) of Kyrgyzstan has detained members of an international criminal group at Manas Airport. The criminals had organized a black-market channel for the illegal sale of human organs abroad. All detainees are citizens of the Kyrgyzstan. According to the investigation, the criminal group looked...

Islamic State – Khorasan Province: An Element of Geopolitical Rivalry?

In the aftermath of the terrorist attack in Moscow, the media has once again been saturated with discussions about the terrorist group Islamic State – Khorasan Province (ISKP), also known as ISIS-Khorasan and “Wilayat Khorasan.” At this point, most of the coverage has focused on the Afghan wing of Islamic...

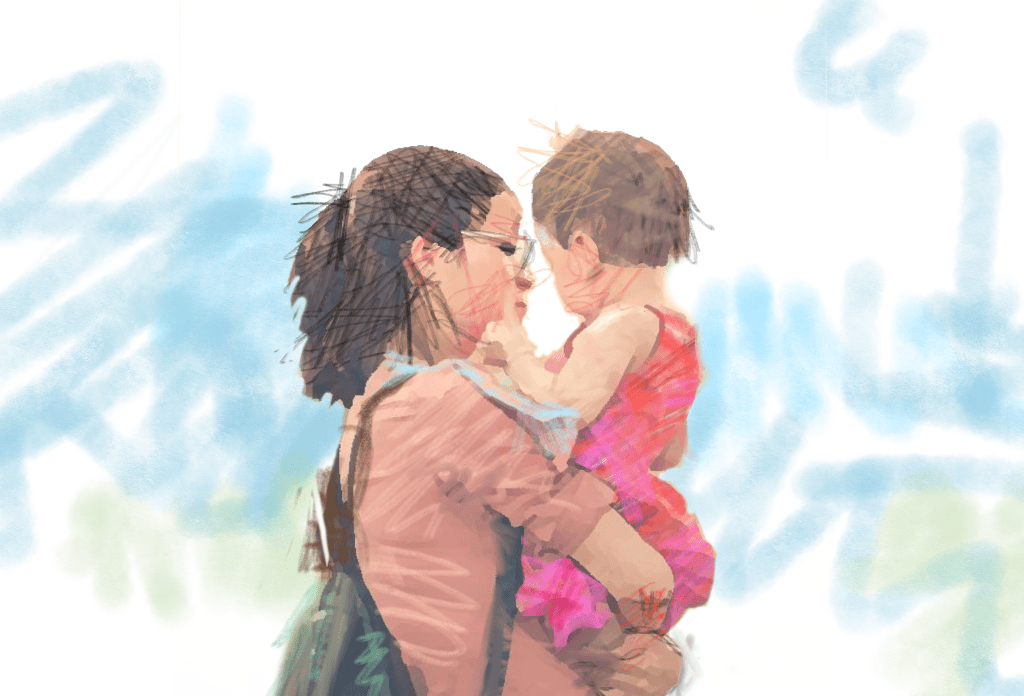

Kazakhstan President Signs Landmark Legislation on Domestic Violence

On April 15, President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev signed into law amendments and additions passed by Kazakhstan’s parliament on April 11 on legislative acts and the code on administrative offenses on ensuring the rights of women and the safety of children. The initiative represents a first in the CIS in terms of...

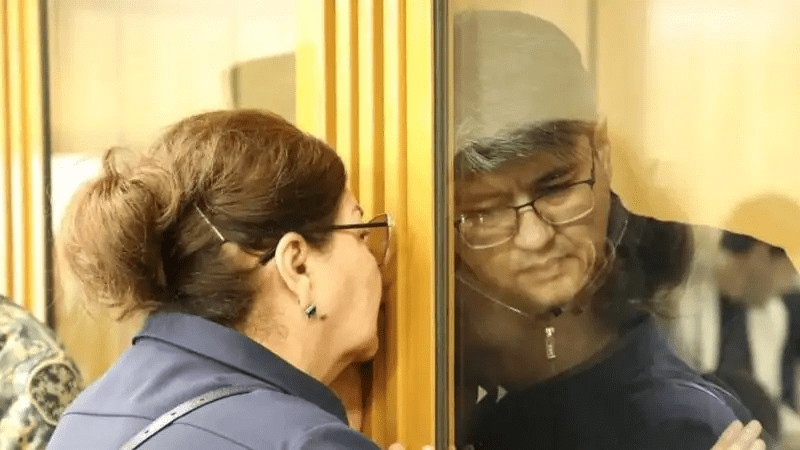

The Bishimbayev Trial: The Women of Kazakhstan Speak

The trial of the trial of former Minister of the Economy, Kuandyk Bishimbayev, has ignited discussions across Kazakhstan, particularly among women. Online actions and rallies across Europe have been organized in memory of the victim, Saltanat Nukenova, and the Senate has passed a law strengthening protections for women and children...

As Bishimbayev Case Continues, Kazakhstan Toughens Domestic Violence Laws

While a court in Astana tries former economy minister Kuandyk Bishimbayev for murdering his wife Saltanat Nukenova, the Kazakhstani Senate has passed a law strengthening protections for women and children against domestic violence. The new law, if properly implemented, can hand out much harsher punishments to those who abuse those...

Kyrgyzstan Minister Says Case Against Media Workers Not About Politics

BISHKEK, Kyrgyzstan – Kyrgyzstan is pushing back against international criticism of a high-profile prosecution of media workers, saying the case is not politically motivated and that those facing charges of inciting mass unrest are poorly educated people masquerading as journalists. Minister of Internal Affairs, Ulan Niyazbekov, said the case against...

Kyrgyzstan Court Moves Four Journalists from Prison to House Arrest

BISHKEK, Kyrgyzstan - Four journalists in Kyrgyzstan who were jailed in January on suspicion of inciting mass unrest have been moved to house arrest, while four others accused in the same case remain in pretrial detention. A district court in Bishkek ordered the release on Tuesday of the former employees...

Online Viral Action #ZaSaltanat: Women of Kazakhstan Oppose Stereotypes About Domestic Violence

The trial of Former Minister of National Economy of Kazakhstan, Kuandyk Bishimbayev, accused of murdering his wife, Saltanat Nukenova, continues. During the hearing, Bishimbayev's lawyers have repeatedly attempted to emphasize that Saltanat, who died from a beating, led a promiscuous lifestyle, including the constant consumption of alcohol. Such arguments caused...

No Lessons Being Learned From Kazakh Floods, Says Political Analyst

Kazakhstan has been prone to flooding before, but the 2024 Kazakh floods have added a catastrophic page to the chronicles. Political analyst Marat Shibutov tells The Times of Central Asia that only extremely tough measures can motivate ministers and akims (local government executive) to actually work on flood prevention. ...

Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan Consider Joint-Stock Company to Build Kambarata HPP-1

Kazakhstan’s Ministry of Energy has announced that the draft Agreement between the governments of Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, and Uzbekistan on the joint implementation of the construction and operation of Kambarata hydroelectric power plant (HPP)-1 has been posted on Kazakhstan’s official Internet portal Open Legal Acts. Available for public discussion, the agreement...

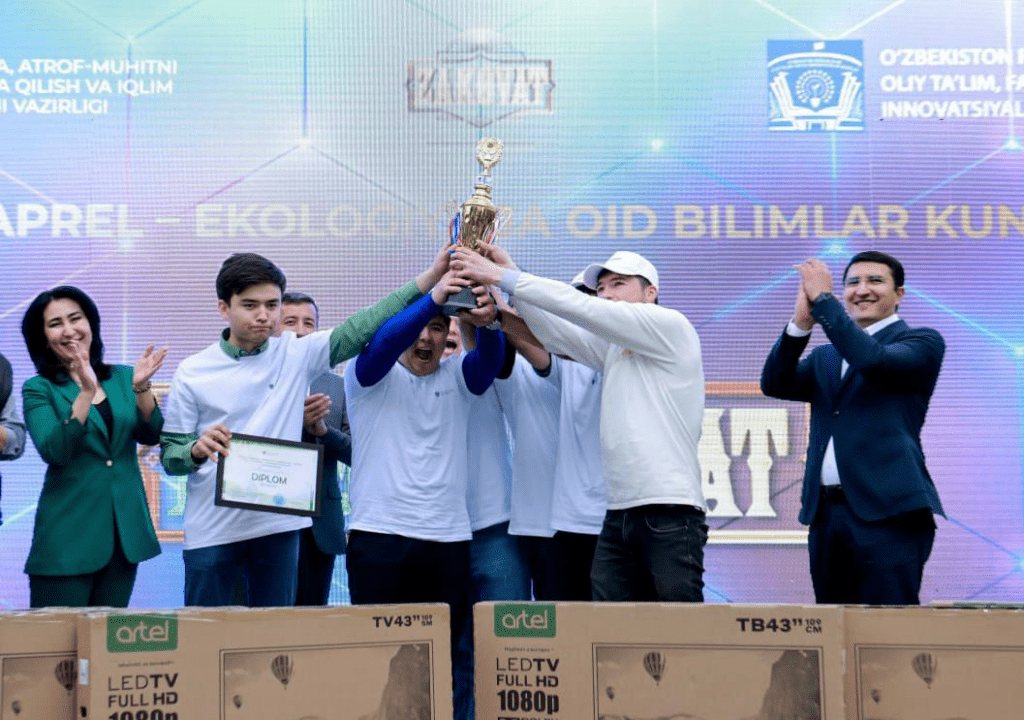

“Eco-Enthusiasts” – Tashkent Hosts Environmental Competition for Students

On April 13, an environmental awareness competition, "Eco-Enthusiasts" was held in Tashkent's Zahiriddin Muhammad Babur Central Ecopark. The event was organized in accordance with the decree of the President, "On measures for effective work of the Ministry of Ecology, Environmental Protection and Climate Change," and was timed to coincide with...

Chinese Invest in Solar Power for Kyrgyzstan

On April 12, the Chairman of the Cabinet of Ministers of the Kyrgyz Republic, Akylbek Japarov unveiled plans for the construction of a solar power plant near Balykchy in the country’s northern Issyk-Kul region. Financed with an investment of $400 million by a Chinese company, the plant will have a...

USAID Oasis Project on Course to Restore Aral Sea Ecosystem

The U.S. Embassy in Kazakhstan has announced that from 12 – 16 April, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) will visit the Oasis project on the former shores of the Aral Sea in the Kyzylorda region of Kazakhstan. Launched in 2021, the Oasis is integral to Environmental Restoration...

Turkmenistan Using Almost All Available Water Resources With No Additions in Sight

Meteojournal has reported that Turkmenistan's State Statistics Committee has published a voluntary national review of its progress in implementing the global agenda for sustainable development until 2023 on its website. According to MeteoJournal, in 2021, almost all water resources in the country – 92% – went to agricultural needs. Another 5%...

Uzbekistan to Host Eco Race in Support of Aral Sea Region

On April 18 in Moynaq, Karakalpakstan, organizers Prorun will host an Aral Sea Eco Race with a total distance of two kilometers. Participants will run one km to the location of a tree planting, plant a tree, and then return. At the finish line, each participant will receive a medal...

Kazakhstan Faces Unprecedented Threats from Floods, Droughts, Locust Infestations

Experts are predicting a severe drought in Kazakhstan. Additionally, locusts are expected to invade the country, and the flood situation will be even worse next year. That's according to Kazakhstani ecologist, Dmitry Kalmykov, who further explained to the Times of Central Asia in an interview that climate change in the...