Kazakhstan plans to join in the Trans-Afghan Corridor project by constructing a 120-kilometer railway from Turgundi to Herat and establishing a transport and logistics center on Afghan territory. The new route is expected to expand the volume and improve the efficiency of Kazakhstan’s export and import shipments, while also providing access to the Indian Ocean, the Middle East, and the Persian Gulf.

In August, Kazakhstan’s Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of National Economy, Serik Zhumangarin, announced that the country plans to invest $500 million in the construction of the Turgundi-Herat railway in Afghanistan. The 120-kilometer line will provide the shortest route to the Indian Ocean, linking Kazakhstan and Central Asia with Pakistan’s seaports of Karachi and Gwadar.

Kazakhstan’s Deputy Minister of Transport, Zhanibek Taizhanov, told The Times of Central Asia that the project is expected to take about three years from the approval of the design and cost documentation.

“More precise timelines will be determined after the completion of all design stages, approvals, and the signing of contracts with contractors and investors,” said the ministry representative.

The railway will give Kazakhstan access to new transport routes and markets. Amid intensifying global competition for transit flows, it offers a cheaper alternative shipping option and represents an important new logistics solution for the republic.

This promising route, however, also carries risks, as Afghanistan remains one of the world’s most unstable countries. Even so, trade potential between Kazakhstan and Afghanistan is considerable. In 2024, bilateral trade turnover reached $545.2 million, with $527.7 million accounted for by Kazakh exports. Kazakhstan remains one of Afghanistan’s largest trading partners and a leading supplier of grain and flour.

Looking ahead to exports and imports moving toward Pakistan, India, and beyond, the potential is considerable. Yet market participants have repeatedly noted that logistics remains the main barrier to trade in this direction.

“Projected freight volumes along the route are estimated at 35–40 million tons per year. A comprehensive study of the region’s economic potential, logistics flows, and expansion prospects is underway,” Taizhanov told TCA, adding that once operational, the line is expected to become a crucial link in the international transport system, boosting trade between Central Asia and South Asia.

In Afghanistan, the Taliban resumed nearly all regional and interregional transport projects initiated under the previous government. Active negotiations are underway on the construction of the Termez–Naibabad–Maidan Shahr–Logar–Kharlachi line, commonly referred to as the “Kabul Corridor,” the Mazar-i-Sharif–Herat railway, and the completion of the Khaf–Herat line, among others.

Regional countries have also joined this large-scale effort. The Trans-Afghan project involves the interests of Russia, China, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, and Iran, all of which are seeking to benefit from its implementation.

Geopolitics and transport interests

In pursuit of greater export, import, and transit opportunities, Kazakhstan, Russia, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan are actively participating in these initiatives, offering their own rail routes through Afghanistan to Pakistan’s borders. For Iran and Tajikistan, the transnational corridor through Afghanistan is also attractive, providing a potential route to China via Kyrgyzstan.

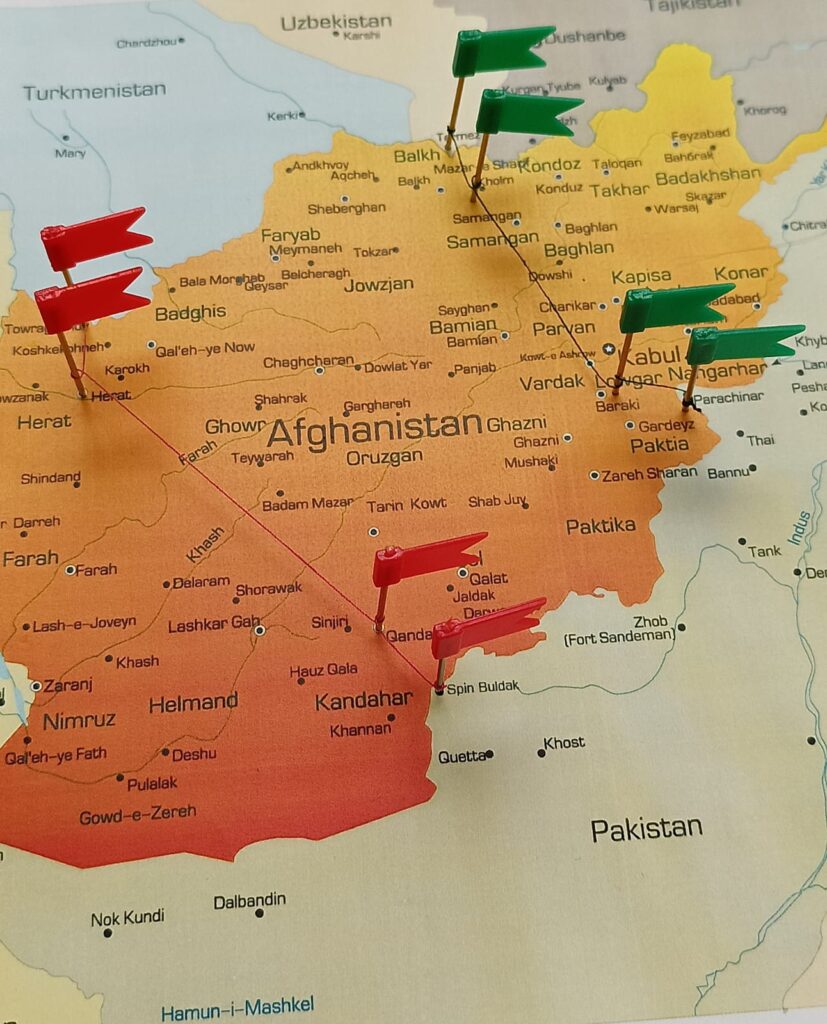

Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan plan to implement the Turgundi–Herat railway, with a future extension to Kandahar and Spin Boldak. The corridor will connect Kazakhstan to Afghanistan through Turkmenistan’s railway network, passing from the Bolashak–Serkhetyaka crossing to Serkhetabad–Turgundi, then on through Herat and Kandahar to the Spin Boldak–Chaman crossing with Pakistan. This “western” route of the Trans-Afghan Corridor will stretch more than 900 kilometers and is expected to cut cargo delivery times between Central and South Asia nearly tenfold.

The “eastern” section, about 650 kilometers long, will run from Uzbekistan’s border through Termez–Naibabad–Maidan Shahr–Logar–Kharlachi and will be carried out by Uzbekistan. In July, an intergovernmental agreement was signed in Kabul to develop a feasibility study, and Russia is also expected to join.

In April, the Russian and Uzbek transport ministries, along with the railway administrations of both countries, signed documents to advance the project. Russia, which views the Trans-Afghan Corridor as part of its logistics strategy, plans to complete freight volume forecasts for the route by 2026, with preliminary estimates of 8 to 15 million tons annually. The economic feasibility study is expected in early 2026, according to Russian Deputy Prime Minister Alexei Overchuk at the Russia–Afghanistan business forum, held during the 16th International Economic Forum “Russia–Islamic World: KazanForum.” Russia also sees Trans-Afghan development as a possible extension of its flagship North–South Transport Corridor to Pakistan and India.

Iran, with its unique geography, already provides an alternative to Afghan transit for shipments between Russia and Pakistan via the Caspian Sea and land routes through Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan. Iran is also interested in the Turgundi–Spin Boldak corridor, which would link Afghanistan to Iran’s Chabahar port via Zaranj. In 2020, Iran began building the Chabahar–Zahedan railway to support this goal.

Tajikistan has also joined the race. In July 2024, the country’s Ministry of Transport, together with the Korea International Cooperation Agency, signed a protocol to develop a feasibility study for the 51-kilometer Jaloliddin Balkhi–Lower Pyanj railway, which would connect Tajikistan to Afghanistan. In the future, it could become part of the planned Southern Corridor, known as the “Road of Five Nations,” linking China, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Afghanistan, and Turkmenistan.

Access to global markets for these countries depends on Kazakhstan due to geography. Therefore, the corridor is expected to provide an alternative route: through the Turkmen port of Turkmenbashi on the Caspian Sea, across the Caucasus to Turkey and Europe, and via Iran and Afghanistan to India and the Middle East. Although this route is planned to bypass Kazakhstan, the creation of a transport and logistics hub in Herat will allow the country to take part in the processing, accumulation, and distribution of cargo flows along the Southern Transport Corridor. Herat is thus becoming an important junction in the transit routes between Western, Central, Southern, and Eastern Asia.

A key issue in implementing infrastructure projects in Afghanistan, apart from the country’s difficult mountainous terrain, is the width of the railway gauge for the new line. At present, Afghanistan’s railway network extends just over 300 kilometers. Its largest segments are the Khaf–Herat line, stretching 225 kilometers across the country, and the Termez–Mazar-i-Sharif line, 75 kilometers long.

The first segment was financed by Iran and the Islamic Development Bank and was built with a 1,435 mm gauge, the same as in Iran. The Termez–Mazar-i-Sharif line was constructed according to the Russian standard of 1,520 mm. As a result, in seeking funding for infrastructure projects, Afghanistan has had to contend with the fact that each neighboring country built railways to suit its own needs. Meanwhile, Pakistan uses a 1,676 mm gauge, inherited from colonial times and shared with India. This situation requires either transshipment of goods or the replacement of rolling stock bogies to fit another gauge, leading to delays. This remains one of the negative factors in cargo logistics.

The question of what gauge the new line will adopt is therefore critical. For Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan, from whose border the project will begin, both of which use the Russian gauge, it would certainly be preferable if the entire line were built to the 1,520 mm standard.

Financial prospects and risks

Financing remains a critical issue. Kazakhstan has allocated $500 million for the first stage of the project, but funding questions are still under review. Options include domestic resources, support from international financial institutions, and participation by strategic foreign partners and investors.

“The main task is to ensure a reliable and sustainable financial model that will contribute to the effective implementation of the project,” said Taizhanov.

For Kazakhstan, the new railway line in Afghanistan not only diversifies export routes and develops transit shipments but also creates opportunities to export domestic construction services and supply rail materials such as rails, sleepers, and fasteners. This generates foreign exchange revenues and jobs for Kazakh construction, engineering, and industrial companies.

Kazakh firms already have experience in Afghanistan. Between 2020 and 2023, Integra Construction KZ helped build the international Khaf–Herat railway between Iran and Afghanistan, a major project with an annual throughput capacity of 12 million tons. It connected the railway networks of the two countries, enabled bilateral trade by rail, and gave Afghanistan access to the sea. The Turgundi–Herat project will also be carried out by a Kazakh company, though no specific enterprise has been named. Taizhanov noted that a domestic contractor is expected, with proven expertise in similar projects, to strengthen both regional cooperation and the role of national companies in international infrastructure.

Beyond construction and investment, Kazakhstan faces the challenge of ensuring safe and transparent transport conditions along the corridor. Security risks are tied to the international community’s stance toward the Taliban, as well as to tensions in Pakistan–Afghanistan and India–Pakistan relations. According to Taizhanov, security remains a priority at all stages. Risk assessments will be conducted during the preparation phase, covering both geopolitical and infrastructure aspects.

“All security measures will be reflected in the relevant documentation and developed in coordination with international partners and specialized bodies. Cooperation with local authorities and international organizations is also envisioned to ensure stability and protect key infrastructure,” said the Deputy Minister of Transport.

The Trans-Afghan Corridor will require heavy investment, modernization of transport infrastructure, removal of administrative barriers, and closer regional cooperation. At the same time, each planned railway to Pakistan’s borders could become a competitor, raising the risk of regional fragmentation. Success will depend on making individual corridors efficient, reliable, and attractive to international shippers.

Amid global changes in trade routes, every country and every transport corridor can play a pivotal role in international logistics. What matters most is not only building infrastructure and improving performance but also ensuring sustainable, predictable, and competitive logistics that global shippers can trust.