The presidents of Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan gathered in the northern Tajik city of Khujand on March 31 for a meeting that is decades overdue. Among the agreements the three signed were one fixing the border where their three countries meet.

Prior to Uzbek President Shavkat Mirziyoyev’s arrival, Kyrgyzstan’s President Sadyr Japarov and Tajikistan’s President Emomali Rahmon exchanged ratified documents of the border agreement between the two countries. Rahmon and Japarov, via video link, also launched the Datka-Sughd power transmission line, a major step in the CASA-1000 project that aims for both their countries to supply electricity to Afghanistan and Pakistan.

These agreements might not seem monumental, but they represent a major departure from the troubled past the three governments have had in their border areas.

Trouble in Paradise

The three countries share the Ferghana Valley, an area roughly the size of Costa Rica that is home to more than 20% of Central Asia’s population. Since the Central Asian states became independent in late 1991, the Ferghana Valley has also been the region’s hotbed of tension.

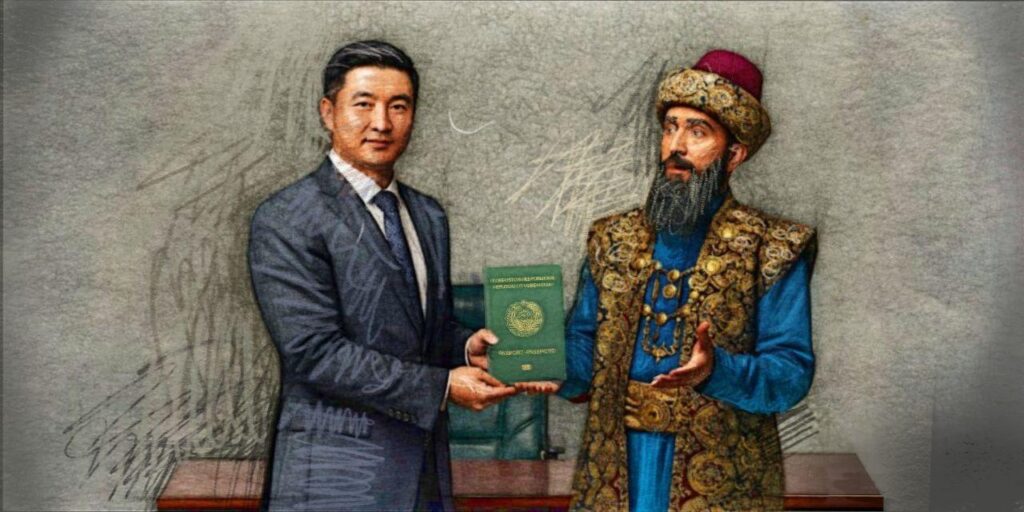

The Ferghana Valley is the cradle of ancient Central Asian civilization. Some living there today say it was the location of the Garden of Eden, and it is not difficult to see why. The Valley is abundant in fruits and vegetables and has extensive arable and grazing land. It is surrounded by mountains to the north, east, and south, and the rivers that flow from these mountains supply ample water.

Since independence, the Ferghana Valley has been the most dangerous place in all of Central Asia. The arbitrary borders Soviet mapmakers drew to divide Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan left many problems for the three after they became independent states. Agreement on where Kyrgyz-Uzbek border is came only in late 2022, and Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan just signed the agreement on delimitation of their border on March 12.

The Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan

The roots of Islam lie deep in the Ferghana Valley. There were already calls for Shari’a law in Uzbekistan’s section of the valley just months after Uzbekistan declared its independence.

The most serious security threat to Central Asia to date originated in the Ferghana Valley in 1999 and 2000.

In early August 1999, a group of some 20 armed militants from the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU) appeared in southern Kyrgyzstan, captured a village, and took the villagers and subsequent government negotiators hostage.

The IMU leaders were from the eastern Uzbek city of Namangan. They were connected to the protests in Uzbekistan in late 1991 and later joined the Islamic opposition in neighboring Tajikistan’s 1992-1997 civil war. The peace accord that ended the civil war called for opposition fighters to either join the Tajik armed forces or disarm. There was no longer any need for the opposition’s foreign fighters, and the final phase of disarmament was underway by the summer of 1999.

In mid-August, the Kyrgyz government paid a ransom for the hostages’ release and the departure of the IMU militants, but this provided only a brief respite. Hundreds of IMU militants entered Kyrgyzstan several days later, seizing several villages and the people living in them.

The IMU released a statement clarifying that the group’s goal was to overthrow then-Uzbek President Islam Karimov and asking Kyrgyzstan to open a corridor through Kyrgyz territory to Uzbekistan.

Karimov warned Kyrgyzstan not to allow the IMU militants to reach Uzbekistan, and the Kyrgyz and Uzbek authorities criticized the Tajik government for not taking action to neutralize IMU bases in Tajikistan’s mountains. The Tajik government denied the militants had bases in Tajikistan, though it was clear the IMU fighters could only have entered southern Kyrgyzstan from Tajikistan.

The IMU withdrew from Kyrgyzstan in October as winter approached, after collecting another ransom from the Kyrgyz government.

In the summer of 2000, the IMU returned to southern Kyrgyzstan, and entered the mountain regions of southeastern Uzbekistan. Uzbekistan had already started placing landmines along parts of its border with Kyrgyzstan after the 1999 incursion, and when the militants appeared in Uzbekistan, the Uzbek military evacuated mountain villages and put landmines in the area along the Tajik border.

Dozens of Kyrgyz and Tajik civilians, mainly shepherds or people gathering firewood, were killed or wounded by these landmines in the years that followed. It took five years for Uzbekistan to start removing the landmines from the Kyrgyz border area, and it was not until 2020 that Uzbek sappers removed the last of the landmines from the Tajik border.

Unmarked Borders

After independence, there were difficulties between the Central Asian states in finding agreement on where exactly their frontiers should be, and many sections remained disputed for decades.

The root cause of the 2021 and 2022 border battles between the Kyrgyz and Tajik militaries was disputed land and water rights in unmarked areas of their frontier. The open conflict came after a decade of clashes between communities along the Kyrgyz-Tajik border.

Since independence, incidents of civilians straying into the territory of a neighboring country have been common.

In the Ferghana Valley, after the 1999 and 2000 IMU incursions, Uzbekistan’s border guards took no chances along the country’s frontier with Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan. From 2000 until President Mirziyoyev came to power in 2016, Uzbek border guards shot dozens of people, some fatally, who crossed from Kyrgyzstan or Tajikistan, often unintentionally, into usually poorly marked or unmarked Uzbek territory.

The enclaves in the Ferghana Valley have also been scenes of conflict.

Tajikistan’s Vorukh enclave has been at the center of many of the conflicts in southern Kyrgyzstan, and the fighting between the Kyrgyz and Tajik armies in 2021 and 2022 raged all around the enclave.

The situation has been little better around Uzbekistan’s Soh enclave that is surrounded by Kyrgyzstan. Soh once was on the main road connecting the Kyrgyz cities of Osh and Batken, but after the IMU incursions, Uzbekistan restricted passage through Soh. That required Kyrgyzstan to build a new section of road that avoided Soh.

An incident in July 2009, when Kyrgyz border guards allegedly beat a teenager from Soh because he could not speak Kyrgyz, sparked tensions. In May 2010, residents of Soh stopped several vehicles with Kyrgyz license plates, beating the passengers and damaging the cars. Residents of several nearby Kyrgyz villages responded by blocking the road to Soh, prompting Uzbekistan to temporarily send additional armored vehicles to Soh.

Inter-ethnic violence broke out between Kyrgyz and Uzbeks in southern Kyrgyzstan days after the Soh stand-off. The conflict was unrelated to the events in Soh, but it left more than 400 people dead, mostly Uzbeks, thousands of people injured, caused widespread damage in the areas in and around Osh and Jalal-Abad, and sent several hundred thousand Uzbeks fleeing into Uzbekistan, or remaining just on the Kyrgyz side of the Uzbek border.

Uzbekistan closed its border with Kyrgyzstan at that time, and that border remained closed until September 2017.

Tensions around Soh continued. In May 2020, residents of Soh and Kyrgyz villagers clashed when a dispute broke out over water use. More than 100 people were injured, and several houses were burned down.

Uzbekistan had greatly restricted traffic crossing its border from Tajikistan since the days of Tajikistan’s civil war, and often, the border was entirely closed until March 2018.

Just a few years prior to the border reopening, Tajik-Uzbek relations had sunk so low that rather than using an existing Soviet-era railway line that connected Uzbekistan’s section of the Ferghana Valley to Tashkent, Uzbekistan spent $1.9 billion to build the Angren-Pap railway line that avoided Tajik territory.

A New Beginning?

These are just a few of the more publicized problems in the Ferghana Valley in the last nearly 34 years. There have also been accusations of one of the three countries attempting to quietly and illegally remark sections of the border. Uzbek troops occupied the Ungar-Too area in Kyrgyzstan twice in 2016.

There was flooding, drought, illegal narcotics trafficking through the Ferghana Valley, and other problems that affected all three countries.

It is extraordinary that through all of this, the leaders of the three countries sharing the Ferghana Valley never held a summit to discuss solutions to the many challenges their countries face. That is what makes the summit in Khujand a special event that can hopefully lay the groundwork for easing tensions and peacefully sharing and developing the potential of the Ferghana Valley.