Kinship Clans in Modern Kazakhstan: Historical Continuity and New Realities

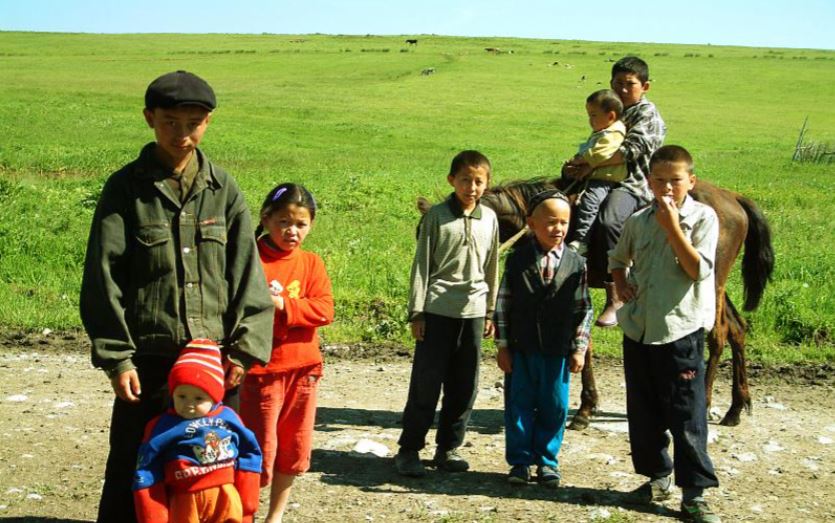

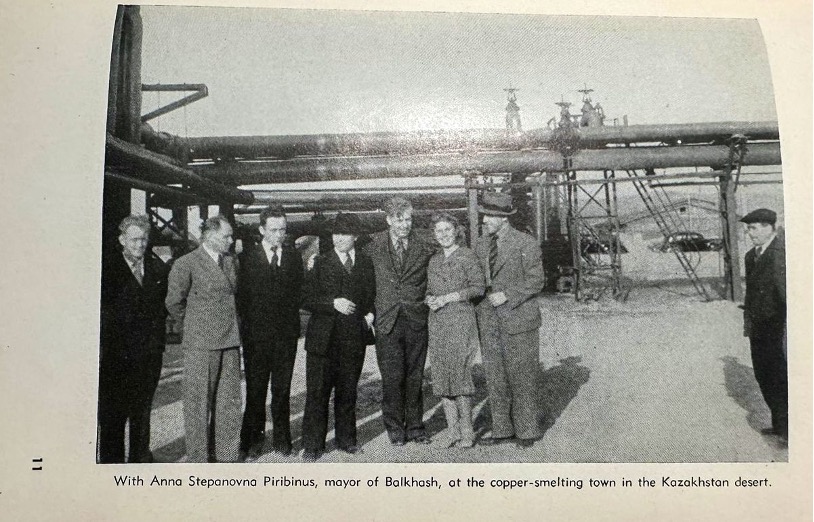

Ancestral ties are seemingly embedded in the DNA of every Kazakh. This tradition, rooted in antiquity, reflects the clan structure that historically shaped Kazakh society. The notions of zhuz (a set of clans) and ru (clan) largely determined the social organization of the nomadic lifestyle. Kazakh society traditionally consisted of three zhuzes, the Older, Middle, and Younger which in turn united many clans. The zhuzes were large tribal unions, a kind of higher-level “horde” that included dozens or even hundreds of distinct clan groups (ru), while ru referred specifically to a group of close blood relatives. Such clan structures formed the basis of traditional society. Historical Roots: The System of Zhuzes and Shezhire The origin of the three Kazakh zhuzes remains a subject of historical debate. In early written sources from the 17th century, the names of the zhuzes had not yet been formalized. Chronicles described only a geographic custom: those living in the upper reaches of a river were called the “Big zhuz,” those in the middle the “Middle zhuz,” and those in the lower reaches the “Younger zhuz.” The 16th-century work Majmu al-Garaib mentions Kazakhs but notes that the terms Uly zhuz, Orta zhuz, and Kishi zhuz were not yet in use. The classical three-zhuz system only fully formed by the late 17th to early 18th century, during the reign of Tauke Khan (1680-1715), when the Kazakhs united under a single Kazakh Khanate. According to a legend recorded by traveler G. N. Potanin, one ruler gathered 300 warriors and divided them into three groups: the first hundred, Uly zhuz, were settled upstream along the Syr Darya; the second hundred, Orta zhuz, in the middle; and the last hundred, led by the chief Alshin, downstream as Kishi zhuz. These legends provide a cultural explanation for the emergence of the zhuzes, though historians stress there is no single agreed version. Hypotheses range from military-administrative divisions into “wings” to the influence of geography and climate across Semirechye, Saryarka, and Western Kazakhstan. Alongside the zhuz system, clan identity was reinforced through genealogical chronicles, shezhire, in which Kazakhs recorded their ancestors’ names and clan history. Knowledge of seven generations (jeti ata) was obligatory for every Kazakh and was absorbed “with mother’s milk”. These genealogies had practical implications: knowing one’s lineage helped determine kinship laws, including prohibitions on marrying within the same clan. The clan was not just a social structure, but a fundamental part of identity. As publicist Khakim Omar wrote: “The main idea of the shezhire is revealed in the close connection of ancestors’ and descendants’ names, in the continuity of generations,” allowing a person, through genealogy, “to define their place in the world”. Transformation of Tradition in the Soviet Era Under Soviet rule, internationalism and a break from “tribalism” were officially promoted. Yet in practice, the clan system continued to operate informally as a mechanism of social mobility and legitimacy. While divisions into zhuzes and clans were no longer legally recognized, they endured as a way of thinking, a cultural filter...