Kazakhstan’s Emerging Role in Global Rare-Earth Supply Chains

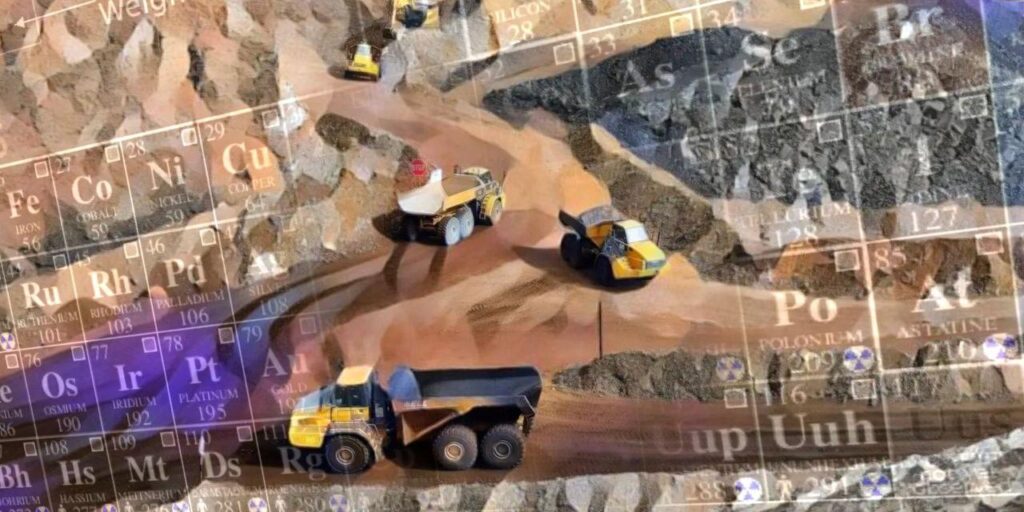

October 10 was one of the most consequential days for global trade policy and one of the most volatile for world markets since the U.S.–China tariff conflict first reignited. After China announced tighter export controls on rare earths, U.S. President Donald J. Trump first posted on Truth Social that “there seems to be no reason” anymore for him to meet with the Chinese leader Xi Jinping at the APEC summit in two weeks' time. Several hours later, the official White House account on X posted a message from Trump that he had learned that "effective November 1st, 2025, [China will] impose large-scale Export Controls [sic] on virtually every product they make, and some not even made by them." He then followed with the declaration that the U.S. will impose a 100% tariff on Chinese imports starting November 1, "or sooner," and launch export controls on critical software. As Washington and Beijing escalate their economic confrontation, the scramble for stable rare-earth supply chains has broadened beyond East Asia. Attention is shifting to Central Asia, where mineral potential and trade corridors align with the broader effort to reduce dependence on China. Kazakhstan has drawn particular attention, not as a single solution, but as a state seeking to leverage its Soviet-era industrial base and access to the Caspian to help meet emerging supply chain needs. Although Kazakhstan has made the most progress in translating its mineral reserves into a functioning mining industry, it remains part of a broader regional effort to diversify away from a single external partner, most notably China. Other Central Asian states are testing their own capabilities to meet global supply chain demands, though most remain constrained by infrastructure, financing, or lack of processing capability. Kazakhstan’s Position in the Emerging Supply Realignment On reserves, Kazakhstan’s rare-earth potential is rooted as much in continuity as it is in discovery. Decades of geological mapping under Soviet administration established its mineral profile, and recent joint surveys by Kazgeology and private firms have both confirmed and expanded those earlier findings. New delineated deposits in the east and center of the country, including the Zhana Kazakhstan site in Karagandy, have reinforced its status as a prospective non-Chinese source of critical materials, with verified concentrations of neodymium, praseodymium, dysprosium, terbium, and samarium. If current resource estimates are validated, the Zhana Kazakhstan deposit could rank among the largest rare-earth reserves in the world. These elements are essential inputs for high-efficiency magnets used in electric vehicles, wind turbines, and advanced defense systems. The U.S. Department of Defense classifies these rare earths as “critical defense materials,” a designation that underscores their strategic relevance rather than any immediate shift in supply. Both the Pentagon and the Defense Logistics Agency have begun increasing stockpiles and exploring alternative processing sources, but for now, the question in Kazakhstan is not geological endowment, which is established, but the terms under which that endowment can be brought to market. On processing capacity, Kazakhstan’s experience in large-scale mining of uranium, copper, and other critical minerals has...