Big Security Sweep After Attack in Tashkent Region; No Casualties

Authorities in Uzbekistan are searching for suspects who opened fire on a vehicle in the Tashkent region early Saturday, the prosecutor general’s office said. The office did not immediately confirm some Uzbek media reports that Komil Allamjonov, former chief of the presidential information department, may have been in the vehicle. There were no injuries in the attack, which occurred around 1:40 a.m. while a person identified only as “citizen S.S.” was driving a Range Rover in Qibray district, according to a statement of the prosecutor general’s office. It said “two unidentified individuals fired multiple shots at the vehicle from a firearm and then fled the scene.” The type of weapon used in the attack has not been determined, the statement said. An attempted murder case was opened and a search is underway. “Currently, a rapid investigation group consisting of qualified officers from relevant agencies has been formed, and investigative actions are ongoing,” the prosecutor general’s office said. Gazeta.uz, an Uzbek media outlet, said a large group of law enforcement officials converged on the area where the shooting occurred. It quoted an unidentified person as saying police were asking for video recordings from nearby surveillance cameras. Allamjonov had worked as head of the presidential press service and held other posts prior to becoming chief of the presidency’s Information Policy Department in August 2023. Saida Mirziyoyeva, daughter of President Shavkat Mirziyoyev and a senior presidential aide, thanked Allamjonov when he left that job in September this year. Allamjonov said he would go into the private sector.

Uzbekistan’s Cricket Team: We’re Ready For International Matches

Supporters of Uzbek sport have had a lot to celebrate this year. The national football team currently sits at the top of its qualifying group for the 2026 FIFA World Cup, while eight of the country's athletes took gold at this summer's Paris Olympics. But next year Uzbekistan wants to enter the world stage in a more surprising sport: cricket. The Central Asian country joined the game's governing body, the International Cricket Council (ICC), in 2022. As an “Associate” ICC member there are hopes that the Uzbek squad will play its first international matches in 2025, in the Twenty20 (T20) version of the game. T20 games are much shorter than traditional five-day Test matches. The nation's rapid progress is due to Aziz Mihliev, the owner of Tashkent pharmaceutical company Anfa. Mihliev fell in love with the game while living in India, where cricket is the national sport. As the founder and chairman of the O’zbekiston Kriket Federatsiyasi (Uzbekistan Cricket Federation), Mihliev has created the Anfa Cricket Academy in the capital's Yunusobod district, where three practice pitches cover a school playground. The federation invites students at Tashkent’s sports colleges to the academy to try their hand at cricket. Many of the players picked to wear the red and dark blue striped jerseys of the new Anfa Cricket Club are also talented tennis players. Mihliev has also built a cricket ground outside the capital, towards the town of Chirchiq, where a game between Salar Stars and Ferghana Rangers will be played this Sunday. There are plans to turn an abandoned Soviet-era stadium outside Samarkand into Uzbek cricket's second home. Travelling to represent Uzbekistan at global ICC conferences, Mihliev speaks with the ambition of a man who now rubs shoulders with the most influential people in the sport. From one such trip he writes: "My ambition is to see an Uzbekistan national team play a Test match against the England team. And win, of course!" Over 4,000 Uzbeks now play the game regularly at schools and universities, from Tashkent in the north of the country to the southern Surkhandaryo region. Surkhandaryo borders Afghanistan, a passionate cricketing nation that reached the semi-finals of this year's men’s T20 World Cup. And it was to Afghanistan that Mihliev turned when recruiting a former international player to train his national team. Khaliq Dad Noori played a few games for Afghanistan at the beginning of the 2010s, when his own country was at the start of its journey to the top of world cricket. Noori coaches his players in the Pashto language, which his Uzbek students can understand. But cricket in Uzbekistan still has a local flavour. Hitting techniques come straight from games of chilla, an old pastime played with sticks. Bats are known as tuqmoq – the name of a wooden club that Uzbek warriors used to brandish. Although some of Uzbekistan’s best cricketers have only been playing for a year or two, judging by the talent on show during a practice session they would beat most amateur teams in big cricketing countries. Mihliev is taking his Anfa Cricket Club on a tour to the Indian city of Kanpur next month, to give the players exposure to different conditions, and a higher standard of competition. Speaking after the session, Noori is sure that his players have big futures ahead of them – even if some of them are struggling to persuade their families that playing a complicated foreign sport is a worthwhile decision. “In the next 10 years Uzbekistan will be a real cricket country,” he says. “We want to become a full member of the ICC – and for 80% of people in Uzbekistan to understand and love cricket." "In terms of [senior] international matches, we first want to play against countries in our region who are also new ICC members: Mongolia, Tajikistan and Iran. We are working to set up junior [national] teams at the under-14, under-17 and under-19 level." Whether or not the England team ever walks out for a Test match in Samarkand, simply playing games against Mongolia would be very significant for a country that wants to be seen on the world stage. On the concrete pitch in Yunusobod, one of the young players, Kamron, says: "I am proud to be in the national team of Uzbekistan. It takes a lot of responsibility. In the future we will win international competitions with our team, and defend the honour of our country." His teammate Gholib adds: "Our first president Islam Karimov once said that nothing could make the country known to the world faster than sport." Another player, Asadbek, backs them up. "Cricket is a lovely game," he says. "We want to connect with the world, and pass on a message of peace, which the world needs the most right now. I want to see Uzbekistan play the best teams in the world."

***

Jonathan Campion is The Times of Central Asia’s senior editor, and the author of Getting Out: The Ukrainian Cricket Team’s Last Stand on the Front Lines of War.

Two Lost Silk Road Cities Unearthed in Uzbekistan

Aided by laser-based technology, archaeologists in south-east Uzbekistan, have discovered two lost cities that once thrived along the Silk Road from the 6th to 11th centuries AD. As reported by Reuters, one was a center for the metal industry, and the other, indicates early Islamic influence. Located some five kilometers apart, these early fortified outposts are among the largest found on the mountainous sections of the Silk Road. “These cities were completely unknown. We are now working through historical sources to find possible undiscovered places that match our findings,” said archaeologist and lead author of the report, Michael Frachetti of Washington University in Saint Louis. The researchers state that the most expansive of the two, Tugunbulak, covered about 300 acres (120 hectares) and in existence from around 550 to 1000 AD, boasted a population of tens of thousands. As such, it was one of the largest cities of its time in Central Asia, rivaling even the famed trade hub Samarkand, situated about 110 km away, and according to Frachetti, many times larger and more enigmatic than other highland castles or settlements that have been documented in high-elevation Central Asia." The other city, Tashbulak, inhabited from around 730-750 to 1030-1050 AD, was only a tenth the size of its neighbor, with a population perhaps in the thousands. After discovering the first signs of the cities' existence, archaeologists employed drone-based lidar - a technology that floods the landscape with lasers to measure the topography - to map and establish the size and layout of the sites. Findings revealed highly defined structures, plazas, fortifications, roads, homes, and other urban features. An initial dig at one of Tugunbulak’s buildings, fortified with thick earthen walls, uncovered kilns and furnaces, suggesting it was a factory wherein, metalsmiths turned local iron ore into steel. During the 9th and 10th centuries, the region was known for its steel production and researchers are now analyzing slag found on-site to confirm their hypothesis that in addition to trade in livestock and related products such as wool, the metal industry may have been a central feature of Tugunbulak’s economy. According to Franchetti, “Tugunbulak, in particular, complicates much of the historical understanding of the early medieval political economy of the Silk Routes, placing both political power and industrial production far outside the regional ‘breadbaskets’ such as Samarkand." As stated in the report, Tashbulak lacked the industrial scale of Tugunbulak but boasted an interesting cultural feature: a large cemetery that reflects the early spread of Islam in the region. Its 400 graves—for men, women, and children—include some of the oldest Muslim burials documented in the area.“The cemetery is mismatched to the small size of the town," said Frachetti. "There's definitely something ideologically oriented around Tashbulak that has people being buried there." Tugunbulak and Tashbulak are especially remarkable given their altitude, which is roughly comparable to that of the later Inca citadel of Machu Picchu in Peru, and as noted by Frachetti, “The key finding of this study is the existence of large, fortified, and planned cities at high elevation, which is still rare but much more exceptional in ancient times."

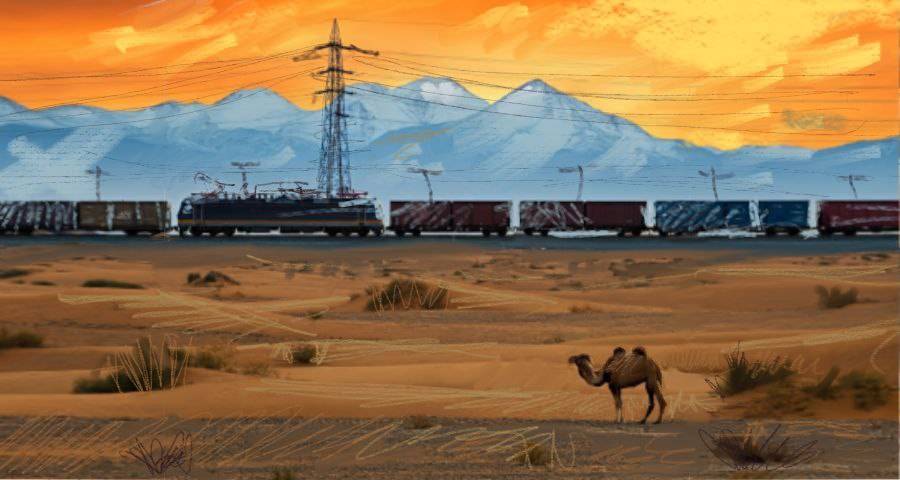

Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan Prioritize Cooperation Between Regions

On October 22, the 4th Interregional Forum, “Uzbekistan-Kazakhstan,” was held in Samarkand, Uzbekistan. The forum addressed issues such as increasing bilateral trade turnover, developing industrial cooperation, and enhancing collaboration in the water, energy, transit, and transport sectors. Speaking at the forum, Uzbekistan’s Prime Minister, Abdulla Aripov, emphasized that developing cooperation between the regions of Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan is a priority in relations between the two countries. Aripov stated that “Over the past seven years, trade turnover between Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan has grown almost 2.5-fold, reaching $4.4 billion last year. Today, more than 1,000 enterprises with Kazakh capital operate in Uzbekistan. Border regions have established direct and close ties with each other — the Republic of Karakalpakstan [in Uzbekistan] with the Mangistau region [in Kazakhstan], the Tashkent region with the Turkestan region, and the Navoi region with the Kyzylorda region. At the same time, this great potential has yet to be realized.” Kazakhstan’s Prime Minister, Olzhas Bektenov, meanwhile, announced at the forum that Kazakhstan is ready to increase exports to Uzbekistan by over $550 million, offering 40 types of high-value-added Kazakh products. Uzbekistan is Kazakhstan’s main trading partner in Central Asia. From January-August 2024, bilateral trade amounted to $2.5 billion, with more than 50% of Uzbekistan’s trade passing through Kazakhstan in transit. The forum paid special attention to the development of industrial cooperation, including 74 joint projects with a total investment volume of $3.4 billion and the creation of 14,600 jobs. Of these, 65 enterprises will be established in Kazakhstan, creating 13,600 new jobs. Examples of Kazakh-Uzbek industrial cooperation include the manufacture of Chevrolet Onix cars in Kostanay (Kazakhstan), a plant for the production of household appliances in Saran (Kazakhstan), sewing, spinning, and weaving factories in the Shymkent and Turkestan regions (Kazakhstan), and the production of autoclaved aerated concrete in Angren (Uzbekistan). Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan are also working on establishing the International Center for Industrial Cooperation “Central Asia,” which will offer “one-stop shop” for services and tax and customs for entrepreneurs from both countries.

Russian Journalist Inessa Papernaya Found Dead in Tashkent Hotel

Russian journalist Inessa Papernaya, known for her work with lenta.ru and profile.ru, was tragically found dead in a hotel in Tashkent, Uzbekistan, on October 20. It has been reported that Papernaya was in Uzbekistan on vacation, and was staying at the Karaman Palace Hotel with a companion, Maxim Radchenko, with whom she was in a long-term relationship, and whom she had traveled with in order to meet his relatives. According to reports, hotel staff knocked on the door of her room that evening while delivering a package. After receiving no response, they entered the room and discovered the bodies of Papernaya and Radchenko. An Uzbek citizen was subsequently found dead in the bathroom of another room in the hotel. Preliminary reports attributed the cause of the deaths to poisoning of “unknown origin,” with early suggestions being propagated that gas seeped into the room through the ventilation system after the hotel’s pool was cleaned on October 19-20, leading to the tragic incident. Following the discovery, authorities sealed off the Karaman Palace Hotel. The General Prosecutor’s Office of Uzbekistan has launched an investigation under Article 186 of the Uzbek Criminal Code, which covers the provision of unsafe services, and a forensic examination has been ordered to determine the precise cause of death. Relatives of Radchenko have disputed what they have described as several different versions of the deaths which have been put forward. According to Radchenko's sister, the family were initially told that "he had an epileptic seizure; she ran up to him, slipped, fell, hit herself and died. This is some kind of TV series: how do you fall? What nonsense... Then there was a version about drugs, since their bodies were in the bathroom, that meant they were drug addicts." In a further twist challenging the official narrative regarding gas seepage related to the pool being cleaned, Radchenko's sister has categorically stated that "there is no pool there." Meanwhile, no websites advertising rooms at the Karaman Palace make any mention of a pool, with some stating outright that this facility is not available. Hayat Shamsutdinov, press secretary of the General Prosecutor’s Office of Uzbekistan, has confirmed that the bodies will be transported to Moscow for a joint cremation to be held on October 25.

Uzbekistan Prepares for the Polls: Embracing a New Electoral System

On October 27, citizens of Uzbekistan will cast their ballots under a new mixed electoral system for the 150-member Legislative Chamber of the Oliy Majlis (Lower House of Parliament) in elections billed as “My choice is my prospering Motherland.” Half of the candidates will be elected from single-member districts using a first-past-the-post system, whilst the other half will come from nationwide proportional representation which requires parties to surpass a 7% electoral threshold. If fewer than one-third of eligible voters participate, the election will be deemed invalid, and should no party meet the threshold for proportional seats, those elections will be considered void. By mandate, at least 40% of the candidates must be women, up from 30% in the elections held in 2019. Additionally, 56 members of the upper chamber, 65 deputies of the Jokargy Kenes of the Republic of Karakalpakstan, 12 regional and 208 district and city council seats are also being contested by approximately 30,000 candidates. At the invitation of the authorities in Uzbekistan, at the end of September, the OSCE’s Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR) dispatched a team of long-term observers. On October 5, Uzbekistan held a groundbreaking pre-election TV debate for party leaders which was broadcast live on multiple TV channels and social media platforms in Uzbek, Russian, English, and Karakalpak. Reportedly modeled on the BBC’s Question Time, the debate’s audience featured voices from the nation's youth, women, and ethnic minorities as part of a drive to engage with voters described by organizers as “innovate, creative [and] interactive. Five parties - the Liberal-Democratic Party of Uzbekistan, Milli Tiklanish (National Revival) Democratic Party, the Ecological Party of Uzbekistan, the People’s Democratic Party of Uzbekistan (PDP), and the Adolat (Justice) Social-Democratic Party – have been registered for the upcoming elections. However, others have faced a backlash for attempting to register. According to The Diplomat, all of the entities running “have always been perceived as mere extensions of the state.” Since the death of long-term despot, Islam Karimov, however, Uzbekistan’s “state apparatus [have] become more open,” as noted by an election observer in 2019, whilst the platforms of figures such as Alisher Qodirov have increasingly chimed with the public. Amidst reforms aimed at tackling endemic corruption, in recent years Uzbekistan has gained ground on Transparency International’s global corruption perception index, and recently partnered with the World Bank on “training, projects, and research to combat corruption.”

Central Asia: Working Together on Border Landscapes

Talk of closer cooperation among Central Asian countries has ebbed and flowed as far back as the period after independence from Soviet rule in the early 1990s. The goal of a more unified region is a work in progress, though one promising area of collaboration is a plan to restore and protect damaged ecosystems in border regions. The first regional meeting on the topic, held this month in Tashkent, Uzbekistan’s capital, brought together government officials from the host nation as well as Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Turkmenistan. The portfolios of the delegates were nature preservation, protected areas, emergencies, agriculture, and forestry. They talked about coordinating on wildfire alert systems in cross-border areas, erosion control, tree-planting and nature-oriented tourism in protected areas and other sites shared by Central Asia countries, according to the Regional Environmental Centre for Central Asia, a non-profit group based in Almaty, Kazakhstan that promotes regional dialogue on the environment. The group, which organized the Tashkent meeting, was created in 2001 by the five Central Asian states as well as the European Union and the United Nations Development Programme. The initiative is supported by a $256 million World Bank program to restore degraded landscapes in the region. The World Bank has noted big progress toward poverty alleviation and economic growth by Central Asian countries in the last decades. However, it has cautioned that oil and gas extraction in Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan have taken a heavy environmental toll, while soil erosion and water scarcity have accompanied land development in Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan. Arid conditions exacerbated by climate change and inefficient management threaten transboundary water resources, a problem that is becoming increasingly severe. “A key example of tragic impacts on livelihoods and health of communities in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan and across the region are massive sand and salt storms originating from the land areas once covered by the Aral Sea,” the Regional Environmental Centre for Central Asia said. It cited an international disaster database as saying more than 10 million people in Central Asia have “suffered from land degradation-related disasters” since 1990, inflicting damages estimated at around $2.5 billion. Central Asian countries also seek to collaborate on early warning systems and other emergency precautions as they face a variety of natural hazards, including floods, landslides and droughts. Supported by United Nations agencies, the heads of the national emergency departments of Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan convened in August at a lakeside resort town in northern Kyrgyzstan. There, they shared information and experiences.

Karakalpak Activists Facing Charges in Uzbekistan, Granted Asylum in the United States

The waiting, worrying, and wondering are finally over for four Karakalpak activists who were detained in Kazakhstan some two years ago, and faced possible extradition back to Uzbekistan. Zhangeldi Zhaksimbetov, Tleubike Yuldasheva, Raisa Khudaybergenova, and Ziuar Mirmanbetova received word on October 15 that they had been granted asylum in the United States. It ended more than two years of uncertainty that started with the unrest in Karakalpakstan on July 1, 2022. Karakalpakstan is part of Uzbekistan, but has a special status as a sovereign republic with its own parliament and constitution that allows the region to hold a referendum on seceding from Uzbekistan. Those unique privileges are also enshrined in Uzbekistan’s constitution, but in spring 2022 parliament proposed making amendments to the constitution. The main reason for the amendments was to change the presidential term from five to seven years so that incumbent President Shavkat Mirziyoyev, who was serving his second and constitutionally last term at the time, could extend his stay in power. However, the commission drafting the constitutional changes also dropped the articles referring to Karakalpakstan’s sovereign status and right to secede. Those rights were nominal as there was no chance Uzbek authorities would allow Karakalpakstan to fully govern itself or secede. Karakalpakstan accounts for some 37% of Uzbekistan’s territory, and also has large oil and natural gas reserves that have just started being developed in the past ten years. The special rights Karakalpakstan had might have been nominal, particularly since ethnic Karakalpaks make up only about one-third of Karakalpakstan’s two million inhabitants. But these distinctions, albeit it only on paper, were important to the Karakalpaks, and when the proposed amendments were published at the end of June 2022, tensions started rising immediately in Karakalpakstan. On July 1, Karakalpak community leaders went to apply for permission to hold a public meeting against the planned changes affecting Karakalpakstan. The group’s leader, activist and lawyer Dauletmurat Tazhimuratov, was detained. Word spread and a large group numbering at least several thousand gathered, protesting peacefully outside the administration building in the Karakalpakstan capital, Nukus. When police and security forces attempted to disperse the crowd, violence broke out, and when it was over and order finally restored, at least 21 people were dead and 243 injured. Nearly all the casualties were Karakalpaks, and police and security forces were accused of using unnecessary and indiscriminate force against the protesters. News of the proposed amendments, and the ensuing violence spread to the Karakalpak communities in other countries, notably to neighboring Kazakhstan, where, according to various estimates, anywhere from 50,000 to 200,000 Karakalpaks live. Most have Kazakh citizenship, but some simply work in Kazakhstan and remain citizens of Uzbekistan. Karakalpak activists in Kazakhstan followed events in Karakalpakstan in late June and early July 2022 and posted about it on social networks, sometimes with words of support for the protesters. After Uzbek authorities had restored order in Kazakhstan and arrested more than 500 people, Uzbek officials requested the Kazakh government detain Karakalpaks in Kazakhstan who had been posting statements and information on social networks before, during, and after the violence. Based on a warrant from Uzbekistan, Zhaksimbetov and Koshkarbai Toremuratov were detained in Almaty on September 13, 2022. Uzbek law enforcement accused them of encroaching on the constitutional order of Uzbekistan and disseminating material that threatened public safety and order in Uzbekistan. On September 16, Karakalpak activist Khudaybergenova was detained in an Almaty suburb on the same charges from Uzbekistan, and at the start of October, Almaty police detained Mirmanbetova. On October 14, 2022, Human Rights Watch released a statement calling on the Kazakh authorities not to extradite the Karakalpak activists to Uzbekistan, but Kazakhstan’s then-Foreign Minister Mukhtar Tleuberdi said his country’s position was that the four were citizens of Uzbekistan. On November 13, Kazakh border guards apprehended Yuldasheva as she was trying to cross the border into Russia. In all five cases, the Kazakh authorities initially ordered the Karakalpaks be held for 40 days, then extended their terms of detention to approximately one year. All were released after that time, but they remained in legal limbo, trying to find political asylum in a third country while always fearing they could be detained again in Kazakhstan at any moment and sent back to Uzbekistan, where they would almost surely be imprisoned. Toremuratov left for Poland, where his request for asylum is still under review. Zhaksimbetov, Yuldasheva, and Khudaybergenova and her family left for the United States on October 15. Mirmanbetova is reportedly waiting for paperwork for a member of her family to be cleared, then they will both also depart for the United States. Several Karakalpak activists are still being held in Karakalpakstan, notably Aqylbek Muratbai, who became the Karakalpaks’ main spokesman on what has been happening in Karakalpakstan since the July 2022 unrest. For these Karakalpak activists remaining in custody in Kazakhstan, the fortuitous turn of events for Zhaksimbetov, Yuldasheva, Khudaybergenova, and Mirmanbetova is a good sign they too might be released from detention and find asylum in the United States.

Sunkar Podcast

Kazakhstan’s Return to Nuclear Power