Abu Dhabi Energy Giant Joins Offshore Gas Project in Turkmenistan

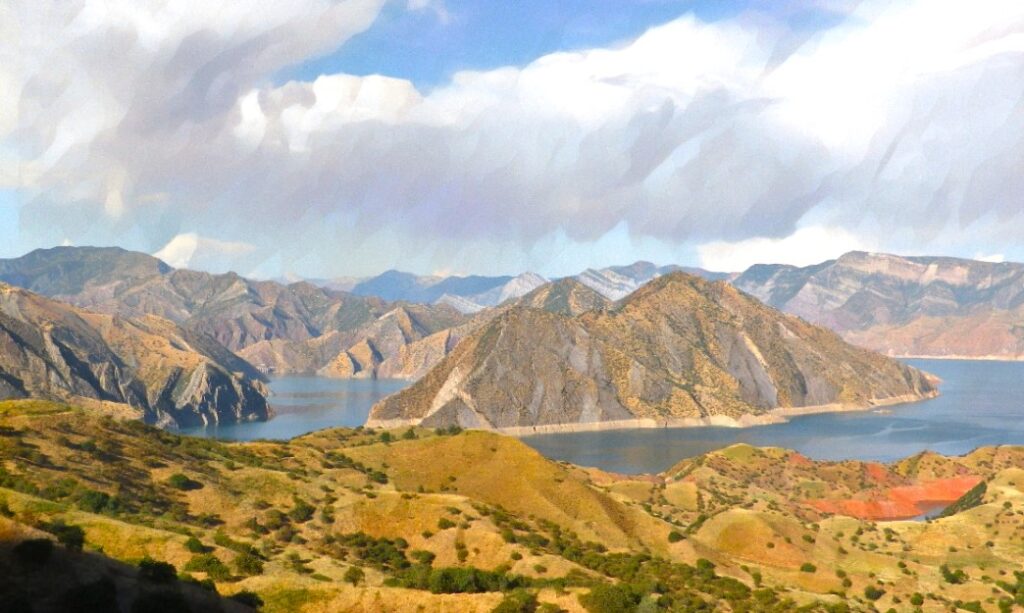

XRG, the international investment arm of the Abu Dhabi National Oil Company (ADNOC), has acquired a significant stake in a major offshore gas project in Turkmenistan’s Caspian Sea sector. The deal was announced on May 14 by energy news outlet Neftegaz, citing the company’s press service. Established in late 2024, XRG manages $80 billion in assets and focuses on global investments in chemicals, natural gas, and renewable energy. The initiative forms part of Abu Dhabi’s broader strategy to diversify its international portfolio and reduce reliance on crude oil exports. Under the new agreement, Malaysia’s state energy company Petronas will retain a 57% majority stake in Caspian Block I. XRG will hold 38%, while Turkmenistan’s state company Khazarnabit will control the remaining 5%. A long-term gas sales agreement was also signed with Turkmenistan’s state concern Türkmengaz. In parallel, Petronas, Khazarnabit, and the state oil company Türkmennebit concluded a new production-sharing agreement for Block I. Located offshore in the Caspian Sea, Block I currently produces approximately 400 million cubic feet of natural gas per day and is estimated to hold over 7 trillion cubic feet in reserves. Petronas has operated in Turkmenistan since 1996 and manages a gas processing plant and onshore terminal in Kiyanly. This latest agreement builds on momentum from a high-level visit by Turkmenistan’s National Leader Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedov to the United Arab Emirates in January 2024. During the visit, ADNOC and Türkmengaz signed a memorandum of understanding to explore joint development of the third phase of the Galkynyş gas field and associated infrastructure.

Turkmenistan’s Arkadag Footballers Left Without Prize Money Despite AFC Victory

The recent triumph of Turkmenistan’s Arkadag football club in the AFC Challenge League, one of Asia’s most prestigious club competitions, has stirred controversy beyond the pitch. While the victory was widely celebrated, players were left without significant financial rewards, as over $1 million in prize money was donated to charity, prompting mixed reactions among fans and observers. The team was honored with a hero’s welcome in the newly constructed city of Arkadag, complete with fireworks and a celebratory parade. However, expectations of substantial bonuses went unmet. Each player received a symbolic $1,000 from President Serdar Berdimuhamedov, a modest sum compared to their tournament earnings. The total prize purse for winning the competition and reaching the final reportedly exceeded $1.5 million. According to official statements, the athletes themselves requested that the funds be donated to the Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedov Charitable Foundation for Children. Despite their international success, the players reportedly earn official salaries of no more than $120 per month. Turkmen football remains largely cut off from global sporting networks, with few foreign players, limited match broadcasts, and minimal competitive depth in domestic leagues. Arkadag’s main rivals frequently field incomplete squads, diminishing the overall level of competition. Sports analysts and development experts warn that the lack of meaningful financial incentives could erode player morale and hinder the growth of football in Turkmenistan. They argue that while charitable contributions are commendable, sustained investment in athletes is essential to build a competitive and inspiring national sports culture.

Despite Ceasefire India-Pakistan Conflict Sends Ripples Through Central Asia

Despite a recent ceasefire agreement between India and Pakistan, renewed hostilities remain a looming threat. The latest clashes between the two nuclear-armed neighbors have direct and potentially lasting repercussions for Central Asia’s political stability and economic development. Ceasefire Amid Escalation Armed conflict erupted on May 7, when New Delhi launched “Operation Sindoor,” targeting what it described as terrorist infrastructure within Pakistan. The move followed a deadly terrorist attack on April 22 in Pahalgam, Jammu and Kashmir, which killed 26 people. India accused Pakistan of complicity, a charge Islamabad rejected, condemning the airstrikes as an “act of war.” Full-scale hostilities ensued for several days, raising alarms across the broader region. By May 11, a ceasefire was brokered, though both sides warned that fighting could resume if provoked. Given the eight-decade-long volatility along their shared border, the risk of future escalations remains significant.

Whilst Pakistan credited the U.S. for facilitating the ceasefire, specifically highlighting Senator Rubio and what it described as direct intervention by President Trump, India maintained that the agreement was a result of direct communication between the Directors General of Military Operations (DGMOs). In a formal televised address, Foreign Secretary Vikram Misri emphasized that the ceasefire was a "bilateral" decision reached via military hotlines, omitting any mention of Trump or Rubio. “Both sides agreed to cease all firing and military actions on land,” Misri stated firmly, reiterating India’s stance that no third party played a role in its interactions with Pakistan.

Disruption to Tourism Flows One immediate economic impact of the conflict has been felt in Central Asia’s tourism sector. In recent years, Kazakhstan, especially Almaty, has become an increasingly popular destination for Indian travelers, aided by a visa-free regime that permits 14-day stays. The country also hosts large numbers of Indian and Pakistani students, along with medical tourists and business travelers. Many Indian visitors rely on budget carriers such as IndiGo, which previously operated routes from Delhi to Almaty and Tashkent using airspace over Pakistan. The closure of this airspace led to increased costs and logistical complications. IndiGo suspended flights to both cities on April 27 and 28, respectively. Should hostilities resume, these suspensions could be extended, potentially setting back Central Asia’s still-fragile tourism recovery. Infrastructure and Trade at Risk The geopolitical instability also jeopardizes key infrastructure projects and trade routes. Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan have both enhanced connectivity with Pakistan through distinct strategies, with Kazakhstan integrating into multilateral frameworks like the Middle Corridor and QTTA, and Uzbekistan focusing on tactical bilateral projects such as the Termez–Karachi transport corridor and Trans-Afghan Railway. Both countries aim to reduce their reliance on Russian-controlled routes while leveraging Pakistan’s ports to boost regional trade. Political analyst Zhanat Momynkulov warns that the conflict could disrupt supply chains and raise the cost of goods across South and Central Asia. The rerouting of flights due to Pakistani airspace closures is already affecting logistics and regional connectivity. Kazakhstan, a central player in both the Shanghai Cooperation Organization and the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), is particularly vulnerable. Projects such as the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), a BRI flagship, could be delayed or derailed. Similarly, the Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India (TAPI) gas pipeline faces heightened uncertainty. Construction on the TAPI pipeline’s Serkhetabad-Herat segment began in September 2024, backed by Turkmen and Afghan officials. The 1,814-kilometer pipeline, fed by Turkmenistan’s massive Galkynysh field, is intended to diversify Turkmenistan’s gas exports and provide a stable energy source to Afghanistan. Escalating regional tensions have now cast doubt over its timely completion. Diplomatic Tightrope for Central Asia The conflict also places Central Asian governments in a delicate diplomatic position. Much like in the context of the war in Ukraine, regional leaders must navigate relationships with powerful and often opposing international actors. China, a major player in Central Asia, maintains a strong military partnership with Pakistan and reportedly supplies it with advanced weaponry and satellite intelligence. According to Kazakh political analyst Adil Kaukenov, this support reflects Beijing’s broader strategic alignment with Islamabad. At the same time, Pakistan enjoys broad backing in the Islamic world, including from Turkey, Saudi Arabia, and Azerbaijan. Conversely, India draws strength from its substantial global diaspora and robust diplomatic ties with the UAE, as well as traditional partners in the U.S., UK, and Canada. Meanwhile, Russia being a longstanding ally of India adds further complexity to the geopolitical equation. Central Asia’s close ties with all these powers mean that any escalation could force regional states into uncomfortable diplomatic balancing acts, with consequences for both domestic and foreign policy.Two Key Environmental Initiatives Completed in Turkmenistan

Turkmenistan has marked the successful completion of two major agro-environmental initiatives aimed at enhancing natural resource management and climate change adaptation. These efforts represent significant progress in addressing environmental challenges both nationally and across the broader Central Asian region. Regional Project on Natural Resource Management The first project concluded was the second phase of the regional program titled “Integrated Natural Resource Management in Drought-Prone and Salinized Agricultural Production Landscapes of Central Asia and Turkey,” which commenced in 2018. This initiative focused on pilot sites in the Karakum Desert, the mountain village of Nokhur, and the Turkmen sector of the Aral Sea region. Key achievements include the establishment of mini GIS laboratories at the Scientific and Information Center under the Interstate Commission on Sustainable Development, the National Institute of Deserts, Flora and Fauna, and within the environmental control departments of the Ministry of Agriculture. These facilities are now equipped with modern tools to support research and monitoring efforts. The project also delivered resource-efficient agricultural equipment, drought-resistant seeds and seedlings, water pumps for various intakes, and rapid soil analysis equipment to agricultural universities. Twenty wells and sardobs (traditional water reservoirs) were constructed for livestock centers and nurseries utilizing drip irrigation systems. Additionally, the project cleaned parts of the collector drainage system and developed reclamation plans to rehabilitate degraded land. Another notable contribution was the continued publication of the international scientific journal “Problems of Desert Development,” which has been issued in Ashgabat since 1967. National Climate Change Adaptation Plan The second completed initiative, “Development of the National Adaptation Planning Process in Turkmenistan”, was carried out by the Ministry of Environmental Protection in partnership with the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and the Green Climate Fund. Launched in 2021, the project sought to implement the National Climate Change Strategy by defining specific adaptation measures and implementation mechanisms. The initiative resulted in the development of a comprehensive Roadmap for implementing the National Adaptation Plan, the creation of a national climate finance concept, and new guidelines for integrating climate adaptation into water resource management. These tools aim to bolster Turkmenistan’s resilience to the adverse effects of climate change. Central Asian Climate Conference in Ashgabat From May 13 to 15, Ashgabat will host the Seventh Central Asian Conference on Climate Change (CACCC-2025), organized by the Regional Environmental Centre for Central Asia (CAREC) with support from the World Bank, CAWEP, RESILAND Tajikistan, and GIZ. CACCC-2025 will serve as a key regional platform to transform climate ambitions into actionable strategies. The agenda includes mobilizing financial resources for adaptation and mitigation, enhancing regional cooperation, and sharing best practices. Participants will engage in plenary sessions, thematic panels, and field visits to sites that exemplify successful adaptation measures. One of the conference’s strategic goals is to develop a plan for increasing regional climate finance by 25% over the next five years. Delegates are also expected to present updated national contributions (NDCs 3.0) under the Paris Agreement and promote cross-border cooperation for sustainable development. With the region facing accelerating climate threats, such as glacier melt, rising temperatures, and land degradation, CACCC-2025 will be a pivotal event for advancing climate resilience and environmental sustainability across Central Asia.

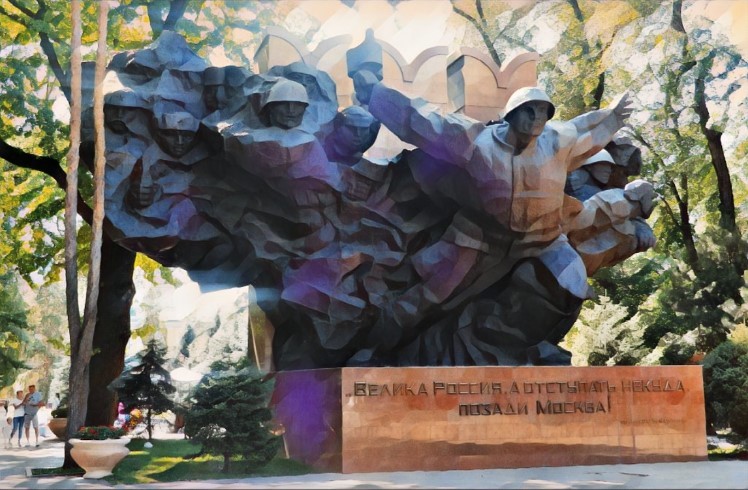

Victory Day in Central Asia: Honoring Sacrifice Amid Shifting Narratives

For the countries of Central Asia, Victory Day holds a deep significance. Although debates over the nature of the May 9 commemorations have intensified in recent years, the importance of the holiday remains unchallenged.

A War That Touched Every Family

Attitudes toward the celebration marking the defeat of Nazi Germany are largely shaped by each nation's level of participation in the war effort. Kazakhstan mobilized over 1.2 million people, nearly 20% of its pre-war population of 6.5 million. Of these, more than 600,000 perished at the front, with an additional 300,000 dying in the rear due to malnutrition, forced labor, and inadequate medical care.

With a similar sized population, Uzbekistan sent approximately 1.95 million people to the front - or one in every three residents. Around 400,000 Uzbeks did not return home. Over 500 Kazakhstani and more than 300 Uzbekistani soldiers were awarded the title Hero of the Soviet Union.

[caption id="attachment_31602" align="aligncenter" width="2560"] Eternal flame and Crying Mother Monument, Tashkent; image: TCA, Stephen M. Bland[/caption]

Kyrgyzstan, home to just 1.5 million people at the time, sent over 363,000 to the front. Approximately 100,000 perished, and 73 received the Hero of the Soviet Union medal. Tajikistan mobilized more than 300,000 troops, with over 100,000 never returning. Fifty-five Tajiks received Hero of the Soviet Union honors. Turkmenistan, with a population of 1.3 million, sent around 200,000 soldiers and officers; 16 received Hero status.

Central Asian soldiers played vital roles in major battles, including the defense of Moscow. They helped liberate territories across the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe. The region also contributed 20-30% of its horse population, then a central component of local economies, for military use.

The war profoundly reshaped Central Asia. Thousands of Soviet enterprises were relocated to the region, fueling industrialization. Millions of refugees from Nazi-occupied zones found sanctuary in Central Asian republics. Many children were taken in by local families and raised as their own.

Today, many in Central Asia feel that outsiders fail to grasp the weight of Victory Day. While countries like the UK, U.S., Italy, and France recorded wartime deaths of 380,000, 417,000, 479,000, and 665,000 respectively, the USSR suffered over 26 million losses. German losses are estimated at 8.4 million.

Celebrating Amid Controversy

Recent years have brought a shift in how Victory Day is perceived in Central Asia. Symbols such as the Guards ribbon, criticized for echoing imperial Russian motifs, have sparked debate. Some argue that the holiday reflects colonial oppression, as the peoples of Soviet Asia were conscripted into a foreign war. These debates have grown louder since Russia annexed Crimea in 2014, with some now viewing the May 9 celebrations as a tool of Russian influence in the region. Nonetheless, Central Asian leaders have rejected efforts to "cancel" Victory Day, reaffirming its deep personal and national resonance.

Efforts to distinguish the celebration from Russian state narratives are evident. Many events now emphasize patriotism rather than Soviet nostalgia. On May 7, Kazakhstan held its first military parade in Astana in seven years, marking both Defender of the Fatherland Day and the 80th anniversary of Victory Day. In Almaty, a procession called Batyrlarğa Tağzym ("Let's Bow to the Heroes") will honor Kazakhstani front-line soldiers. This event mirrors Russia’s "Immortal Regiment" but is positioned within a distinct national context.

Veterans will be honored across the region through concerts, shows, community festivals, and financial support. Kazakhstan plans to name over 500 streets after World War II veterans, according to President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev.

Military parades took place on May 8 in Bishkek and Dushanbe. In Tashkent and other Uzbek cities, major festivities are planned. Uzbekistan is leading the region in veteran support, providing $10,000 to each of the 82 surviving war veterans, one of whom is 114 years old. Kazakhstan will grant $9,686.90 to its 111 veterans. Kyrgyzstan’s 32 remaining veterans will receive $1,140 each. In Tajikistan, 17 veterans will receive $4,810, with those in Dushanbe getting an additional $2,000 from the city administration.

In contrast, Russian veterans will receive less than $1,000 each.

[caption id="attachment_31603" align="aligncenter" width="1280"]

Eternal flame and Crying Mother Monument, Tashkent; image: TCA, Stephen M. Bland[/caption]

Kyrgyzstan, home to just 1.5 million people at the time, sent over 363,000 to the front. Approximately 100,000 perished, and 73 received the Hero of the Soviet Union medal. Tajikistan mobilized more than 300,000 troops, with over 100,000 never returning. Fifty-five Tajiks received Hero of the Soviet Union honors. Turkmenistan, with a population of 1.3 million, sent around 200,000 soldiers and officers; 16 received Hero status.

Central Asian soldiers played vital roles in major battles, including the defense of Moscow. They helped liberate territories across the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe. The region also contributed 20-30% of its horse population, then a central component of local economies, for military use.

The war profoundly reshaped Central Asia. Thousands of Soviet enterprises were relocated to the region, fueling industrialization. Millions of refugees from Nazi-occupied zones found sanctuary in Central Asian republics. Many children were taken in by local families and raised as their own.

Today, many in Central Asia feel that outsiders fail to grasp the weight of Victory Day. While countries like the UK, U.S., Italy, and France recorded wartime deaths of 380,000, 417,000, 479,000, and 665,000 respectively, the USSR suffered over 26 million losses. German losses are estimated at 8.4 million.

Celebrating Amid Controversy

Recent years have brought a shift in how Victory Day is perceived in Central Asia. Symbols such as the Guards ribbon, criticized for echoing imperial Russian motifs, have sparked debate. Some argue that the holiday reflects colonial oppression, as the peoples of Soviet Asia were conscripted into a foreign war. These debates have grown louder since Russia annexed Crimea in 2014, with some now viewing the May 9 celebrations as a tool of Russian influence in the region. Nonetheless, Central Asian leaders have rejected efforts to "cancel" Victory Day, reaffirming its deep personal and national resonance.

Efforts to distinguish the celebration from Russian state narratives are evident. Many events now emphasize patriotism rather than Soviet nostalgia. On May 7, Kazakhstan held its first military parade in Astana in seven years, marking both Defender of the Fatherland Day and the 80th anniversary of Victory Day. In Almaty, a procession called Batyrlarğa Tağzym ("Let's Bow to the Heroes") will honor Kazakhstani front-line soldiers. This event mirrors Russia’s "Immortal Regiment" but is positioned within a distinct national context.

Veterans will be honored across the region through concerts, shows, community festivals, and financial support. Kazakhstan plans to name over 500 streets after World War II veterans, according to President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev.

Military parades took place on May 8 in Bishkek and Dushanbe. In Tashkent and other Uzbek cities, major festivities are planned. Uzbekistan is leading the region in veteran support, providing $10,000 to each of the 82 surviving war veterans, one of whom is 114 years old. Kazakhstan will grant $9,686.90 to its 111 veterans. Kyrgyzstan’s 32 remaining veterans will receive $1,140 each. In Tajikistan, 17 veterans will receive $4,810, with those in Dushanbe getting an additional $2,000 from the city administration.

In contrast, Russian veterans will receive less than $1,000 each.

[caption id="attachment_31603" align="aligncenter" width="1280"] The Turkmen Rifles march in Red Square, Moscow; image: Telegram @ejpredbot[/caption]

Against the backdrop of ongoing conflicts and shifting alliances, all five Central Asian leaders attended this year’s Victory Day parade on Moscow’s Red Square, which speaks volumes about the region’s delicate relationship with Russia. In Moscow, Vladimir Putin vowed that the Russian army would always stand up to “nazism," a narrative previously used by Russia to justify its invasion of Ukraine. In one of a number of growing examples of Central Asia's agency, however, Kazakhstan's President Tokayev has voiced his support for Ukraine’s territorial integrity

The Turkmen Rifles march in Red Square, Moscow; image: Telegram @ejpredbot[/caption]

Against the backdrop of ongoing conflicts and shifting alliances, all five Central Asian leaders attended this year’s Victory Day parade on Moscow’s Red Square, which speaks volumes about the region’s delicate relationship with Russia. In Moscow, Vladimir Putin vowed that the Russian army would always stand up to “nazism," a narrative previously used by Russia to justify its invasion of Ukraine. In one of a number of growing examples of Central Asia's agency, however, Kazakhstan's President Tokayev has voiced his support for Ukraine’s territorial integrity

Victory Day Diplomacy: Central Asia’s Balancing Act and Putin’s Diminished Spotlight

Every year, Moscow’s Red Square transforms into a stage for one of Russia's most celebrated traditions: Victory Day, an event which marks the Soviet Union’s triumph over Nazi Germany in World War II. Yet, as tanks roll through the cobblestone streets and military bands echo under the Kremlin walls, the occasion feels more heavily laden with geopolitical undertones than historical reminiscence these days. Against the backdrop of ongoing conflicts and shifting alliances, the presence of Central Asian leaders at this year’s event speaks to the region’s delicate relationship with the Russian Federation. But the question remains: amidst the pomp and circumstance, is there much for Vladimir Putin to celebrate? Central Asia’s Careful Balancing Act The attendance of Central Asian leaders at the Victory Day parade is a striking show of diplomatic choreography. On the surface, their presence will underscore the shared historical legacy of the Soviet era, when the sacrifices of the Central Asian republics contributed to the Allied victory in the Second World War. However, a more pragmatic lens reveals a balancing act that defines the region’s foreign policy. The region finds itself at the crossroads of global powers vying for influence in Central Asia. While Moscow leans on historical ties and cultural commonalities to retain its sway, Beijing’s economic clout continues to reshape the region’s trade networks and infrastructure projects. Meanwhile, as the inaugural EU-Central Asia Summit attests to, the European Union is eager to expand its reach, whilst hungry for Rare Earth Elements in which the region is rich, the U.S. is waiting in the wings. For Central Asian leaders, participating in Victory Day celebrations signals a nod to Russia’s historic role but also keeps the door open for economic and security cooperation. Amidst the shifting architecture of global politics, their diplomatic strategy remains one of pragmatism, seeking benefits from multiple partners while avoiding any over-alignment. What Does Russia Gain from the Optics? The presence of 29 leaders from across the globe – including Chinese President Xi Jinping - offers Moscow valuable optics at a time when its international relationships face significant strain. Last year, only nine attended. Isolated by Western sanctions over the invasion of Ukraine and with much of the world’s media painting Russia as cut off from the global stage, the impression of a united front with Central Asia helps the Kremlin portray the opposite. Victory Day, therefore, becomes a geopolitical tool, with the attendance of Central Asian leaders enabling Putin to send a message of shared unity within Russia’s historical sphere of influence. It tells both domestic and international audiences that Moscow retains significant allies, reinforcing the image of resilience despite ongoing challenges. How Much Does Moscow Truly Celebrate? The Victory Day parade is an event that is watched by an estimated three-quarters of the Russian public, drumming up patriotism as the state seeks to become the custodian of collective memory. Behind the spectacle, however, signs of disquiet are proving hard to ignore. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has disrupted trade and migration flows central to its ties. The war has also starkly exposed the limits of Moscow’s power. Sanctions have weakened its economy, leaving Central Asia less dependent on Russian investments. Meanwhile, China continues to rise as the dominant force in the region’s economic development, chipping away at Russia’s influence. Even as Central Asian leaders attend events in Moscow, therefore, they tread with caution. Kazakhstan, for example, has refused to recognize Russia’s annexation of Ukrainian territories. President Tokayev has voiced his support for Ukraine’s territorial integrity, making it clear that sovereignty and territorial integrity are also paramount concern for Kazakhstan. This serves to illustrate how the purported unity displayed at Victory Day parades is complicated. While maintaining relations with Russia remains important, Central Asian countries do not want to be drawn into Moscow’s geopolitical confrontations. Central Asia’s Ascendant Voice In the so-called ‘New Great Game,’ Central Asian nations find themselves in a stronger position than before. Their ability to engage both Russia and China while also exploring relationships with the U.S., Turkey, and the European Union, grants them leverage. Leaders in the region are increasingly pushing back when their sovereignty is questioned, as seen in Kazakhstan’s refusal to accede to all of Russia’s demands related to sanctions enforcement and its cautious neutrality over the Ukraine war. A bold stance was also taken by Uzbekistan in its summoning of the Russian Ambassador over annexation comments made by the far right in Moscow. The Real Takeaway from Victory Day For Central Asia, Victory Day celebrations in Moscow are less about solidarity with Russia and more about safeguarding their interests. By attending, leaders strike a delicate balance, acknowledging a shared history without endorsing Moscow’s current actions on the world stage. This calculated diplomacy allows them to ensure stability in their relationships with Russia while continuing to expand alliances with other global powers. For Vladimir Putin, this cautious allegiance may not be a cause for celebration, but it is much needed. Russia’s influence in Central Asia has not completely waned, even if the region’s priorities have shifted. So, while Moscow puts on its grand spectacle, the broader narrative reveals a world where former Soviet republics are increasingly finding their voice, even as they stand in Red Square.

Underground Tunnel Proposed to Channel Water from Black Sea to Caspian Sea

Azerbaijan’s ADOG company, in partnership with Zira Sea Port, has proposed an ambitious plan to construct an underground tunnel linking the Black Sea to the Caspian Sea. The goal is to counteract the rapid decline in the Caspian’s water level, which presents mounting environmental, economic, and infrastructural risks for the five littoral states. According to the analytical portal Minval Politika, the project envisions a 10-meter diameter tunnel connecting the Black Sea, either from the Georgian or Russian coastline, to the Caspian Sea. Engineers propose using the natural elevation difference between the two bodies of water to enable gravity-fed flow from the Black Sea into the Caspian, eliminating the need for pumps. ADOG has stated that the proposed project would undergo comprehensive environmental monitoring and include measures to preserve biodiversity in both marine ecosystems. The company has expressed readiness to begin a feasibility study and initiate the mobilization of necessary resources. Project proponents have submitted a request for the initiative to be considered at the state level and are calling for the launch of preliminary intergovernmental consultations. The urgency behind the proposal is grounded in alarming recent data. As previously reported by The Times of Central Asia, the Caspian Sea has been shrinking at a faster-than-expected rate. Environmental group Save The Caspian Sea reports that the sea level has dropped by two meters in the past 18 years, with projections warning of a further decline of up to 18 meters by 2100 if current trends continue. Such a drop could have catastrophic consequences for regional biodiversity, fisheries, port infrastructure, and climate stability, evoking fears of an ecological disaster akin to the desiccation of the Aral Sea. While the proposed tunnel remains at a conceptual stage, its geopolitical and environmental implications will likely generate serious debate among the Caspian littoral states: Azerbaijan, Iran, Kazakhstan, Russia, and Turkmenistan.

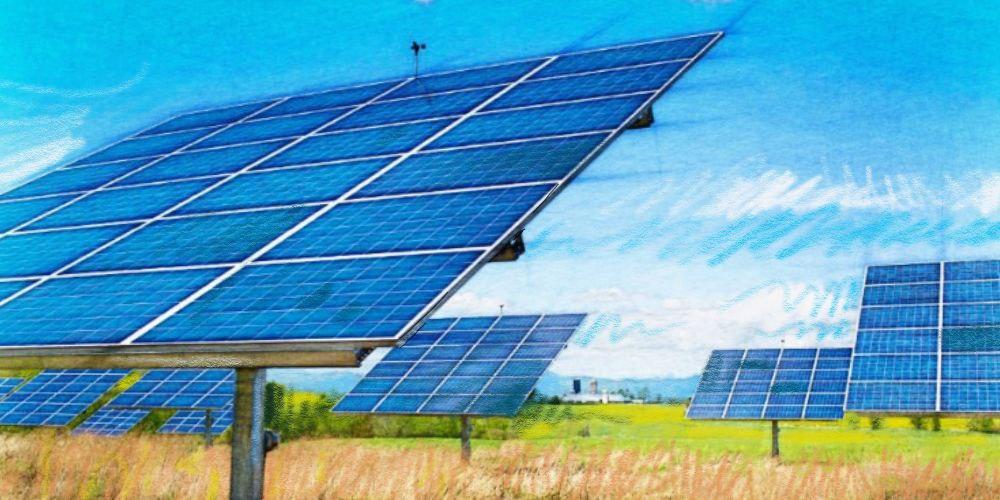

Central Asia’s Green Energy Dream: Too Big to Achieve?

Although most Central Asian nations are heavily dependent on fossil fuel production and exports, they are aiming to significantly increase the use of renewable energy, hoping to eventually become crucial suppliers of so-called green electricity to Europe. Achieving such an ambitious goal will be easier said than done, given that developing the green energy sector in the region requires massive investment. What Central Asian states – struggling to attract long-term private capital into clean energy projects – need is financing for projects that modernize power networks, improve grid stability, and enable cross-border electricity flows. These upgrades are essential for large-scale renewable energy deployment and regional trade in power. Most actors in Central Asia seem to have taken major steps in this direction. In November 2024, at the COP29 climate conference held in Baku, Kazakhstan signed several deals worth nearly $3.7 billion with international companies and development institutions to support green energy projects. Neighboring Uzbekistan, according to reports, has attracted more than €22 billion ($23.9) in foreign investment in renewable energy, while Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan, and Tajikistan – which is aiming to generate all its electricity from green energy sources by 2032 – have developed strategies to help increase their renewable potential. But to turn their goals into reality, all these nations will need funding – whether from oil-rich Middle Eastern countries, China, the European Union, or various international financial institutions. Presently, the development of the Caspian Green Energy Corridor – which aims to supply green electricity from Central Asia to Azerbaijan and further to Europe – remains the region’s most ambitious project. According to Yevgeniy Zhukov, the Asian Development Bank's (ADB) Director General for Central and West Asia, this initiative is a strategic priority for Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, and Azerbaijan. “While the prospect of exporting green electricity to Europe is part of the long-term vision, the core goal of the initiative is to accelerate green growth within the region,” Zhukov told The Times of Central Asia. Together with the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, the ADB is funding a feasibility study for this proposed transmission corridor. The study will assess the technical and economic viability of such a system, along with the environmental and regulatory requirements. In the meantime, the ABD is expected to continue funding other green energy projects in the region. The financial entity, according to Zhukov, invested $250 million in Uzbekistan in 2023 to support renewable energy development and comprehensive power sector reforms, while in other Central Asian countries, it remains “firmly committed to driving the green energy transition.” “For instance, in Tajikistan we are exploring the potential to co-finance the Rogun Hydropower Project alongside the World Bank and other international partners. In Kyrgyzstan, our focus has been on supporting foundational reforms in the energy sector, including strengthening the policy and regulatory environment to attract private investment in renewables. In Turkmenistan, we’ve launched a total of $1.75 million technical assistance initiative to help lay the groundwork for future renewable energy development,” Zhukov stressed, pointing out that these efforts are part of a broader dialogue to support the Central Asian countries’ long-term clean energy ambitions and explore pathways for regional cooperation. In other words, this multilateral development bank, headquartered in the Philippines, is working closely with Central Asian governments to support the transition to cleaner, more sustainable energy systems. As such, the ADB seems to be particularly active in Kazakhstan, where it is helping the authorities “ensure inclusive economic growth, strengthen governance, and address the impacts of climate change.” “To help Kazakhstan achieve carbon neutrality by 2060 and contribute to global climate change mitigation, ADB is supporting the country through various initiatives. They include financing the construction of solar power plants, modernizing a coal-based heat and power plant in Almaty, expanding the high-voltage transmission network in southern Kazakhstan to integrate large-scale renewable energy, and providing advisory support on heat legislation,” Zhukov told TCA, adding that the Bank’s focus in the region’s largest country is to “support the shift from coal to cleaner energy for power, combined heat and power, and heat only boilers.” It is no secret that despite being a major consumer of coal, Kazakhstan is seeking to gradually shut down some of its coal power plants and replace them with renewable or other low-carbon energy sources. Neighboring Kyrgyzstan is also aiming to phase out coal and is therefore looking to ADB for technical assistance in identifying and preparing a pipeline of viable clean energy projects. But the path toward a green energy transition in Central Asia is not without challenges. Key obstacles include an outdated energy infrastructure, regulatory uncertainty, limited regional integration, and competition for investment with more mature renewable markets. Thus, even though Central Asian countries have strong potential to go green, making it happen will take a steady effort, cooperation, as well as continued support from foreign actors seeking to strengthen their presence in this strategically important region.

Sunkar Podcast

Repatriating Islamic State Fighters and Families: Balancing Security and Humanity