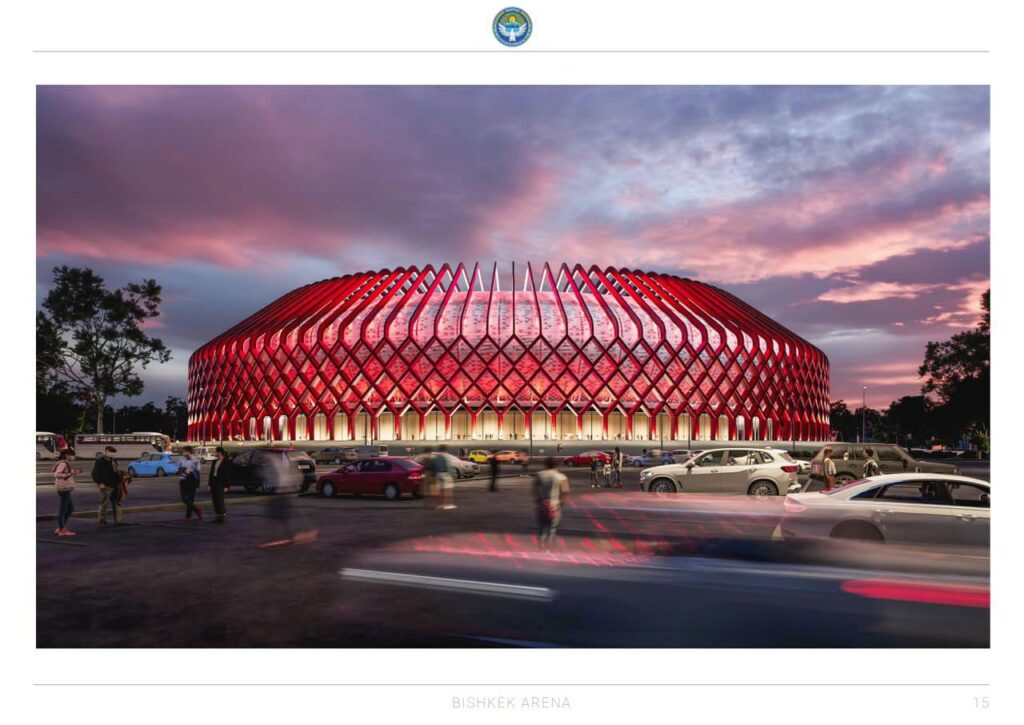

Kyrgyz Football Gets Boost as Construction Starts on New Stadium

Kyrgyzstan is building a 45,000-seat stadium designed to host Asian Football Confederation finals as well as FIFA group matches. This week, President Sadyr Japarov announced that construction on the new stadium near Bishkek had begun and would take two years. Local and Turkish architects and engineers are involved, and there...

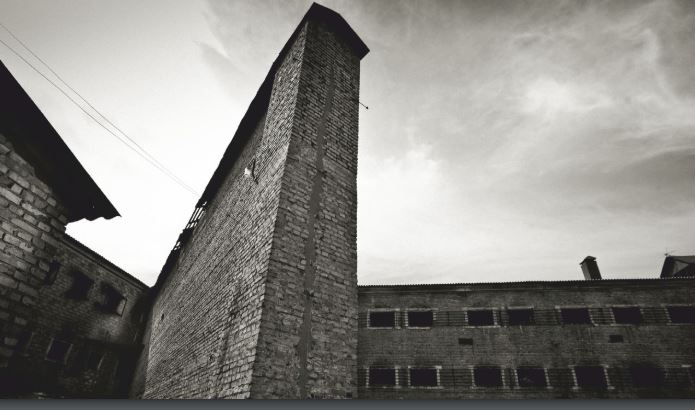

Growth of Non-Custodial Sentences in the Kyrgyz Republic Since 2020

The Kyrgyz Republic has reported a decrease of its prison population, which speaks to the ongoing humanization of its criminal justice system. In 2023, the prison population amounted to just 7,728 persons, a 20% decrease compared to 2020 (9,658 prisoners). Despite a 22% increase in the number of convictions, from...

Britain’s Cameron to Central Asia: Work with Us

Britain’s foreign secretary is in Central Asia this week, seeking deeper ties with a part of the world seen as increasingly vital to international security, energy flows and efforts to combat climate change. The trip, which David Cameron described as overdue, followed criticism that Britain had neglected what the envoy’s...

TikTok Users Struggle to Access App after Kyrgyzstan Announces Restrictions

Kyrgyzstan is restricting access to TikTok. The Ministry of Digital Development sent a letter to internet providers, asking them to block the TikTok social media platform, local media has reported. The ministry cited the network´s failure to comply with a law designed to “prevent harm to the health of children,...

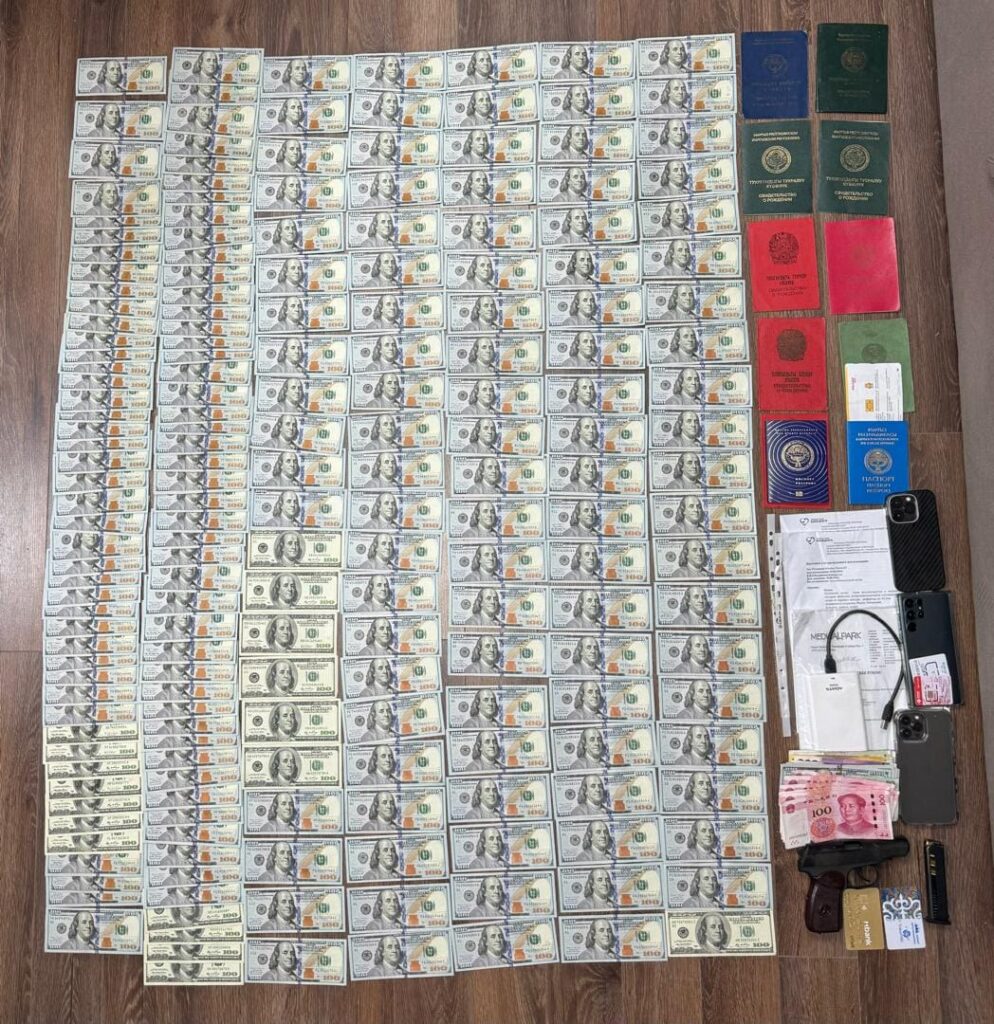

Authorities Find Secret Tunnel Connecting Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan

Another underground passage has been found in the Jalal-Abad region of Kyrgyzstan, which was being used to illegally transport both people and contraband goods into neighboring Uzbekistan. The suspects involved have been arrested. That's according to a report from news outlet, Kaktus, which references information from the press service of...

Open Society to Close its Foundation in Kyrgyzstan, Citing Law on Foreign-Funded NGOs

The Open Society Foundations said it will close its national foundation in Kyrgyzstan after the country’s parliament passed a new law that tightens control over non-governmental groups that receive foreign funding. Open Society, which was founded by billionaire investor and philanthropist George Soros, said Monday that the law“imposes restrictive, broad,...

Kyrgyzstan Battles Misinformation about Vaccines as Measles Cases Rise

Dear parents! Vaccinate your child. That’s the message from the health ministry in Kyrgyzstan, where the number of reported measles cases this year has soared to nearly 8,000 despite government efforts to overcome the anti-vaccine sentiment fueling the outbreak. “It has been proven that there is no connection between vaccinations...

Kyrgyzstan Minister Says Case Against Media Workers Not About Politics

BISHKEK, Kyrgyzstan – Kyrgyzstan is pushing back against international criticism of a high-profile prosecution of media workers, saying the case is not politically motivated and that those facing charges of inciting mass unrest are poorly educated people masquerading as journalists. Minister of Internal Affairs, Ulan Niyazbekov, said the case against...

300 Children Killed on Kyrgyzstan’s Roads

19 hours ago

Central Asians Not Bananas About Bananas

2 days ago

Mudslides in Kyrgyzstan Flood Over 200 Homes

4 days ago

Kyrgyzstan’s Law on NGOs: What Alarms Human Rights Activists?

In April 2024 Kyrgyz President Sadyr Japarov signed a law on non-governmental organizations (NGOs). Now all NGOs must submit full financial reports and register with the Ministry of Justice. Despite the authorities' statements about the need for a document regulating the financing of such organizations, the law has numerous opponents....

Kyrgyzstan’s Debt to China: Another lever of Influence?

Stagnation of the world’s economy, decreasing international trade and growing inflation put the spotlight on the issue of returning Kyrgyzstan’s foreign debt, a large part of which is owed to China. The debt is to be repaid sooner or later, but it would make the country sacrifice either its facilities...

Islamic Extremism in Central Asia: A Threat to Liberal Progress

Afghanistan earned its reputation as the “graveyard of empires” due to the significant toll exacted on foreign powers in their efforts to achieve military success in the country. This challenge was evident in the experiences of the British Empire, the Soviet Union, and, most recently, the United States. The persistent...

Central Asia’s Growing Economic and Strategic Importance Comes to Fore

The Central Asian region has experienced a tremendous economic transformation since the beginning of the century. Its aggregate gross domestic product (GDP) now totals $397 billion, growing 8.6-fold since the year 2000. Its share in global GDP in purchasing power parity (PPP) has also increased 1.8 times. The GDP per...

Authorities Close Religious Institutions in Batken Region

On October 10th, Kyrgyzstan’s State Committee of National Security - comprising representatives from the State Committee of National Security, the Emergency Ministry, the Interior Ministry, Health Ministry, the Grand Mufti's office, other state entities and the regional government. This came following an assessment examining the potential presence of radical Islamic...

Kyrgyz Farmers Urged to Supply Agricultural Products to China

The Kyrgyz Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Water Resources has urged more domestic businesses to establish and expand trade in agricultural produce with the People's Republic of China (PRC). Kyrgyz farmers and processors currently export wheat flour, cherries, melons, grapes and soybeans to China and to increase food exports, the...

Starlink Close to Providing Internet Access in Remote Parts of Kyrgyzstan

Representatives of Kyrgyzstan's ministry of digital development have met again with the American company Starlink, with a view to bringing satellite internet access to the country. However, there are still regulatory hurdles in Kyrgyzstan that hinder the development of Starlink technology. Elon Musk's aerospace company SpaceX first entered the Kyrgyz...

Azerbaijan and Kyrgyzstan Expand Economic and Transport Cooperation

During a state visit to Azerbaijan on 24 April, Kyrgyzstan President Sadyr Japarov joined President Ilham Aliyev in bilateral talks at the 2nd gathering of the Interstate Council of Azerbaijan and Kyrgyzstan. As a result of the meeting in Baku and in support of a joint declaration to deepen relations,...

U.K. Company to Manufacture Innovative Material to Improve Irrigation in Kyrgyzstan

Back in November 2023, Chairman of the Cabinet of Ministers of the Kyrgyz Republic, Akylbek Japarov met head of Concrete Canvas, Will Crawford in Cardiff to discuss the establishment of a plant in Kyrgyzstan. On 23 April representatives of the company travelled to the Chui region of northern Kyrgyzstan for...

Kyrgyzstan and U.S. Review Political, Security and Economic Cooperation

On April 22 Bishkek hosted Annual Bilateral Consultations led by the Deputy Foreign Minister of the Kyrgyz Republic Aibek Moldogaziev and U.S. Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for South and Central Asian Affairs John Mark Pommersheim. Referencing the historic C5+1 Summit held on September 22, 2023 in New York, the...

Central Asian Countries Set 2024 Quotas for Amu Darya, Syr Darya River Water Usage

Last week in Kazakhstan, delegates came together for the 87th meeting of the Interstate Commission for Water Coordination (ICWC) of Central Asia, where they discussed the potential and limitations of regional water reservoirs ahead of the 2023-2024 agricultural growing season. According to the ICWC, some of the more pressing questions...

USAID for Cold Storage Facility in South Kyrgyzstan

The U.S. Embassy in Bishkek has announced that equipment valued at over $78,000 has been provided by the U.S. to Kyrgyz company SFN International LLC to open a modern cold storage facility in Jalal-Abad in southern Kyrgyzstan. Ynakbek Abylkasymov, head of SFN International LLC, reported that the new facility’s 1,100...

Kyrgyzstan Makes Inroads into Silicon Valley

On a visit to San Francisco (USA) on April 21, Chairman of the Cabinet of Ministers of the Kyrgyz Republic Akylbek Japarov was guest of honour at the opening of the High Technology Park (HTP) House of the Kyrgyz Republic in Silicon Valley. Speaking at the event which brought together...

300 Children Killed on Kyrgyzstan’s Roads

The Director of the Situation Centre of the Kyrgyz Republic, Joldoshbek Mambetaliyev, has issued a harrowing report that since 2021, more than 2,000 people including 316 children, have been killed on roads in Kyrgyzstan. Research by the centre cites the prime causes as poor road surfaces, insufficient lighting, lack of...

Starlink Close to Providing Internet Access in Remote Parts of Kyrgyzstan

Representatives of Kyrgyzstan's ministry of digital development have met again with the American company Starlink, with a view to bringing satellite internet access to the country. However, there are still regulatory hurdles in Kyrgyzstan that hinder the development of Starlink technology. Elon Musk's aerospace company SpaceX first entered the Kyrgyz...

Kyrgyz Servicemen Will Be Allowed to Buy Their Military Housing

A new law in Kyrgyzstan allows military personnel who have served in the Kyrgyz army for more than 20 years to purchase their government-issued housing for temporary use. Additionally, families of servicemen killed in the line of duty -- and former members of the military themselves -- can submit claims...

Mudslides in Kyrgyzstan Flood Over 200 Homes

Kyrgyzstan's emergencies ministry has formed an operational headquarters to deal with recent flooding in the south of the country. Rescuers report that hundreds of local residents have been evacuated to safety. Flooding due to heavy rains began last week in Kyrgyzstan's southern Osh region, prompting the region to declare a...

Kyrgyzstan’s Law on NGOs: What Alarms Human Rights Activists?

In April 2024 Kyrgyz President Sadyr Japarov signed a law on non-governmental organizations (NGOs). Now all NGOs must submit full financial reports and register with the Ministry of Justice. Despite the authorities' statements about the need for a document regulating the financing of such organizations, the law has numerous opponents....

Kyrgyzstan Completes Resettlement of Residents From Exclave in Uzbekistan

The Kyrgyz government has completed the resettlement of residents of the Barak exclave, a portion of a country separated from the Kyrgyz mainland that is completely encompassed by Uzbekistan. That's according to a report by the TV channel ELTR. All houses and social infrastructure in Barak were dismantled and moved...

Kyrgyzstan’s Special Services Take On The Drug Mafia

The head of Kyrgyzstan's National Security Service, Kamchybek Tashiyev, has commented that unless it is curbed, the country's already highly complex drug situation is likely to be beyond control within ten years. Speaking at a meeting with heads of Kyrgyzstan's police departments, Tashiyev said that the number of both drug...

Kyrgyz Authorities Seeking Monopoly on Insurance, Industry Group Says

The Kyrgyz Association of Insurers is sounding the alarm that private insurance companies may soon be out of work due to government interference. According to a decree signed by Kyrgyz President Sadyr Zhaparov, all state bodies and local governments are now instructed to insure all their property with the State...

Kyrgyz Farmers Urged to Supply Agricultural Products to China

The Kyrgyz Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Water Resources has urged more domestic businesses to establish and expand trade in agricultural produce with the People's Republic of China (PRC). Kyrgyz farmers and processors currently export wheat flour, cherries, melons, grapes and soybeans to China and to increase food exports, the...

Azerbaijan and Kyrgyzstan Expand Economic and Transport Cooperation

During a state visit to Azerbaijan on 24 April, Kyrgyzstan President Sadyr Japarov joined President Ilham Aliyev in bilateral talks at the 2nd gathering of the Interstate Council of Azerbaijan and Kyrgyzstan. As a result of the meeting in Baku and in support of a joint declaration to deepen relations,...

U.K. Company to Manufacture Innovative Material to Improve Irrigation in Kyrgyzstan

Back in November 2023, Chairman of the Cabinet of Ministers of the Kyrgyz Republic, Akylbek Japarov met head of Concrete Canvas, Will Crawford in Cardiff to discuss the establishment of a plant in Kyrgyzstan. On 23 April representatives of the company travelled to the Chui region of northern Kyrgyzstan for...

Kyrgyzstan and U.S. Review Political, Security and Economic Cooperation

On April 22 Bishkek hosted Annual Bilateral Consultations led by the Deputy Foreign Minister of the Kyrgyz Republic Aibek Moldogaziev and U.S. Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for South and Central Asian Affairs John Mark Pommersheim. Referencing the historic C5+1 Summit held on September 22, 2023 in New York, the...

Britain’s Cameron to Central Asia: Work with Us

Britain’s foreign secretary is in Central Asia this week, seeking deeper ties with a part of the world seen as increasingly vital to international security, energy flows and efforts to combat climate change. The trip, which David Cameron described as overdue, followed criticism that Britain had neglected what the envoy’s...

Kyrgyzstan’s Law on NGOs: What Alarms Human Rights Activists?

In April 2024 Kyrgyz President Sadyr Japarov signed a law on non-governmental organizations (NGOs). Now all NGOs must submit full financial reports and register with the Ministry of Justice. Despite the authorities' statements about the need for a document regulating the financing of such organizations, the law has numerous opponents....

Central Asian Countries Set 2024 Quotas for Amu Darya, Syr Darya River Water Usage

Last week in Kazakhstan, delegates came together for the 87th meeting of the Interstate Commission for Water Coordination (ICWC) of Central Asia, where they discussed the potential and limitations of regional water reservoirs ahead of the 2023-2024 agricultural growing season. According to the ICWC, some of the more pressing questions...

Kyrgyzstan Makes Inroads into Silicon Valley

On a visit to San Francisco (USA) on April 21, Chairman of the Cabinet of Ministers of the Kyrgyz Republic Akylbek Japarov was guest of honour at the opening of the High Technology Park (HTP) House of the Kyrgyz Republic in Silicon Valley. Speaking at the event which brought together...

Kyrgyz Football Gets Boost as Construction Starts on New Stadium

Kyrgyzstan is building a 45,000-seat stadium designed to host Asian Football Confederation finals as well as FIFA group matches. This week, President Sadyr Japarov announced that construction on the new stadium near Bishkek had begun and would take two years. Local and Turkish architects and engineers are involved, and there...

Kyrgyzstan and U.S. Review Political, Security and Economic Cooperation

On April 22 Bishkek hosted Annual Bilateral Consultations led by the Deputy Foreign Minister of the Kyrgyz Republic Aibek Moldogaziev and U.S. Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for South and Central Asian Affairs John Mark Pommersheim. Referencing the historic C5+1 Summit held on September 22, 2023 in New York, the...

USAID for Cold Storage Facility in South Kyrgyzstan

The U.S. Embassy in Bishkek has announced that equipment valued at over $78,000 has been provided by the U.S. to Kyrgyz company SFN International LLC to open a modern cold storage facility in Jalal-Abad in southern Kyrgyzstan. Ynakbek Abylkasymov, head of SFN International LLC, reported that the new facility’s 1,100...

U.S. Helps Decrease Tuberculosis Mortality Rates in Kyrgyzstan

U.S. Embassy Deputy Chief of Mission Liz Zentos and Kyrgyzstan’s Minister of Health Alymkadyr Beishenaliev, attended a national conference on 17 April to review the Cure Tuberculosis partnership. Since 2019, the U.S. government has invested more than $20 million in curing tuberculosis in Kyrgyzstan through the U.S. Agency for International...

Google to Help Transform Kyrgyzstan’s School Education System

On his recent visit to Washington, Chairman of Kyrgyzstan’s Cabinet of Ministers Akylbek Japarov signed a memorandum of understanding with the Google Corporation to transform Kyrgyzstan’s school education system. During the meeting with Google Vice President of Government Affairs & Public Policy Mark Isakowitz, Prime Minister Japarov gave a presentation...

Low-Income Kyrgyz Citizens Offered Financial Literacy Training

Kyrgyzstan's Ministry of Labor, Social Security and Migration has begun to provide training in financial literacy for low-income citizens from all over the country. Those wishing to participate in the state program known as "Social Contract" were offered free training on the basics of entrepreneurship, marketing and financial literacy. At...

Authorities Find Secret Tunnel Connecting Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan

Another underground passage has been found in the Jalal-Abad region of Kyrgyzstan, which was being used to illegally transport both people and contraband goods into neighboring Uzbekistan. The suspects involved have been arrested. That's according to a report from news outlet, Kaktus, which references information from the press service of...

Kyrgyz Climber in Nepal Sets Sights on Three of the World’s Highest Peaks

The head of Kyrgyzstan’s mountaineering federation is in Nepal, preparing to climb three of the world’s highest peaks in the next few months. First up for Eduard Kubatov is the Himalayan mountain of Lhotse. Next is Makalu. Both are more than 8,000 meters high. Three years ago, Kubatov unfurled the...

Growth of Non-Custodial Sentences in the Kyrgyz Republic Since 2020

The Kyrgyz Republic has reported a decrease of its prison population, which speaks to the ongoing humanization of its criminal justice system. In 2023, the prison population amounted to just 7,728 persons, a 20% decrease compared to 2020 (9,658 prisoners). Despite a 22% increase in the number of convictions, from...

Kyrgyzstan’s Special Services Take On The Drug Mafia

The head of Kyrgyzstan's National Security Service, Kamchybek Tashiyev, has commented that unless it is curbed, the country's already highly complex drug situation is likely to be beyond control within ten years. Speaking at a meeting with heads of Kyrgyzstan's police departments, Tashiyev said that the number of both drug...

Traffickers of Human Organs Detained in Kyrgyzstan

The State Committee for National Security (SCNS) of Kyrgyzstan has detained members of an international criminal group at Manas Airport. The criminals had organized a black-market channel for the illegal sale of human organs abroad. All detainees are citizens of the Kyrgyzstan. According to the investigation, the criminal group looked...

Kyrgyz Authorities Name Causes of Military Helicopter Crash

The Chief of Staff of the Kyrgyz Armed Forces has told reporters that the helicopter that crashed outside of Bishkek in January was in good order at the time. Ruslan Mukanbetov named severe weather conditions and human error as the causes of the crash. On 17 January a Mi-8 MTV...

Kyrgyzstan Minister Says Case Against Media Workers Not About Politics

BISHKEK, Kyrgyzstan – Kyrgyzstan is pushing back against international criticism of a high-profile prosecution of media workers, saying the case is not politically motivated and that those facing charges of inciting mass unrest are poorly educated people masquerading as journalists. Minister of Internal Affairs, Ulan Niyazbekov, said the case against...

Kyrgyzstan Court Moves Four Journalists from Prison to House Arrest

BISHKEK, Kyrgyzstan - Four journalists in Kyrgyzstan who were jailed in January on suspicion of inciting mass unrest have been moved to house arrest, while four others accused in the same case remain in pretrial detention. A district court in Bishkek ordered the release on Tuesday of the former employees...

Kyrgyzstan Assassination Plot: Suspected Crime Boss Raimbek Matraimov Held in Pretrial Detention

The corrupt Kyrgyz oligarch Raimbek Matraimov will spend the next month in pretrial detention in Bishkek, after the former deputy head of Kyrgyzstan’s customs service was extradited from Azerbaijan on Tuesday. Matraimov, once known as the country’s “kingmaker” for the influence his clan held over the Kyrgyz Government, was found...

Former Kyrgyz Official Matraimov Extradited in Connection with Assassination Plot

According to statements issued by the special services of Kyrgyzstan, former deputy head of the customs service Raimbek Matraimov is connected with assassins who recently came to Bishkek from Azerbaijan to assassinate members of Kyrgyzstan's leadership. On March 23 Kyrgyz law enforcement became aware that the wanted Matraimov was in...

U.K. Company to Manufacture Innovative Material to Improve Irrigation in Kyrgyzstan

Back in November 2023, Chairman of the Cabinet of Ministers of the Kyrgyz Republic, Akylbek Japarov met head of Concrete Canvas, Will Crawford in Cardiff to discuss the establishment of a plant in Kyrgyzstan. On 23 April representatives of the company travelled to the Chui region of northern Kyrgyzstan for...

Mudslides in Kyrgyzstan Flood Over 200 Homes

Kyrgyzstan's emergencies ministry has formed an operational headquarters to deal with recent flooding in the south of the country. Rescuers report that hundreds of local residents have been evacuated to safety. Flooding due to heavy rains began last week in Kyrgyzstan's southern Osh region, prompting the region to declare a...

TikTok Users Struggle to Access App after Kyrgyzstan Announces Restrictions

Kyrgyzstan is restricting access to TikTok. The Ministry of Digital Development sent a letter to internet providers, asking them to block the TikTok social media platform, local media has reported. The ministry cited the network´s failure to comply with a law designed to “prevent harm to the health of children,...

Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan Consider Joint-Stock Company to Build Kambarata HPP-1

Kazakhstan’s Ministry of Energy has announced that the draft Agreement between the governments of Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, and Uzbekistan on the joint implementation of the construction and operation of Kambarata hydroelectric power plant (HPP)-1 has been posted on Kazakhstan’s official Internet portal Open Legal Acts. Available for public discussion, the agreement...

Chinese Invest in Solar Power for Kyrgyzstan

On April 12, the Chairman of the Cabinet of Ministers of the Kyrgyz Republic, Akylbek Japarov unveiled plans for the construction of a solar power plant near Balykchy in the country’s northern Issyk-Kul region. Financed with an investment of $400 million by a Chinese company, the plant will have a...

World Bank Boosts Kyrgyzstan’s Agricultural Productivity and Climate Resilience

The World Bank has announced funding of $30 million to help boost the productivity and climate resilience of Kyrgyzstan’s dairy and horticulture agri-food clusters. The project will be complemented by a $5 million grant from the Global Agriculture and Food Security Program. “Recognizing agriculture as a cornerstone of the Kyrgyz...

Construction of Waste Processing Plant Launched in Bishkek

On 29 March, Akylbek Japarov, Chairman of the Cabinet of Ministers of the Kyrgyz Republic, participated in a ceremony to mark the construction of a plant to produce electricity coupled with the disposal of solid household waste in the city of Bishkek. He was joined by the Mayor of Bishkek,...

Kyrgyzstan’s First Tire Recycling Plant to Produce Crumb Rubber for Sports Grounds

On March 26th, Akylbek Japarov, Chairman of the Cabinet of Ministers of the Kyrgyz Republic, visited a tire recycling plant in the city of Tokmok in northern Kyrgyzstan. The Kumtor Gold Company has invested 19.2 million US dollars in an enterprise which uses German technology to re-tread tires of any...