Ecological Limit: Five Year Countdown to Water Scarcity in Central Asia

Combating climate change requires collective action by all or a sufficient majority of the world's players supporting global initiatives. Otherwise, it may soon be too late to take any action. To address the issue, the Eurasian Development Bank, the CAREC Think Tank, and the Asian Development Bank organized a two-day forum entitled “The Climate Challenge: Thinking Beyond Borders for Collective Action,” in Almaty, Kazakhstan. Focusing on means of achieving genuine regional cooperation on Asian climate action, the eighth CAREC Think Tank Development Forum was attended by policymakers, experts, and opinion leaders from more than 30 countries. The extensive two-day dialog, consisting of eight sessions, opened with a discussion on the effectiveness of current global initiatives related to climate change: the Paris Agreement, the Global Environment Facility, and the Green Climate Fund. Attention then turned to deepening cooperation among as many stakeholders as possible through multilateral platforms such as the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change. Asia's role in the global fight against climate change, and the difficult balancing act between economic growth and decarbonization efforts were discussed at length. Simply put, the rapid growth of the Asian economy is inevitably accompanied by an increasing consumption of energy, the generation of which leads to increased emissions and pollution. Climate damage due to human impact can be halted and even reversed. However, because this can only be achieved with technological intervention, it poses problems for developing economies unable to afford advanced technologies. Hence, establishing a framework and mechanisms for global technology transfer were key to discussions. Water and finance were also high on the agenda and the subject of a paper presented by Arman Ahunbaev, Head of the Center for Infrastructure and Industrial Research of the Eurasian Development Bank on “Ways to close the investment gap in the drinking water supply and wastewater sector in Central Asia." Ahunbaev reported that 10 million people, or 14% of the population in Central Asia, do not have access to safe drinking water and warned that without intervention, the situation would reach the point of no return in the coming years. To prevent this from happening, he stressed the urgent need for solutions to four problems. The first problem is a twofold increase in the volume of water intake for municipal and domestic needs, based on past figures which showed a growth from 4.2 cubic kilometers in 1994 to 8.6 cubic kilometers in 2020. The second problem is the severe deterioration of water supply infrastructure and treatment equipment, and the third, technological and commercial water losses in distribution networks. The fourth problem is related to the demographic boom and, consequently, the rapid urbanization of Central Asia's population. Cities are expanding and their infrastructure needs to develop accordingly. According to experts, in 2023, urbanization in Central Asian countries will reach 49%, and by 2050, 61%. By 2030, the urban population will exceed that in rural areas. Ahunbaev noted the need for improvement in financing the water supply and sanitation sector in Central Asia since according to rough estimates, the regional deficit in this area is around 12 billion dollars or 2 billion dollars annually. He proposed strengthening public-private partnership as a potential solution, whereby the water sector would be reformed to allow expansion of ownership and management of its enterprises. “It is necessary to improve legislation so that there would be an opportunity to attract, among other things, private capital. We see that the state's budget is limited. Hence, the idea is to develop public-private partnerships and open the possibility of attracting private capital,” Akhunbayev explained. The expert clarified that rather than transferring the sector's enterprises and facilities entirely into private hands, his proposal would provide an opportunity for private investors to invest alongside the state, to help it fulfil its remit. “But the state must retain its leading role," stressed Ahunbayev. " International experience only talks about this. But private capital can greatly help professional management.” Another possible measure to correct the situation regarding the region's water sector is to prioritize investments, optimize the volume of funds attracted, and free up a significant share of capital investments. The EDB also believes it necessary to improve tariff policy, i.e., to raise tariffs, which in Central Asian countries today, are around five times lower than those in Europe. “Tariff setting functions should be gradually transferred to the water supply and wastewater sector enterprises. But -should only be implemented- under the supervision of local executive bodies or an independent regulator and with public participation,” added Ahunbayev. To prevent possible water shortages, Central Asian countries need to make institutional and legal decisions regarding the creation of precise inter-sectoral coordination mechanisms, help restore project expertise, train engineering and technical personnel and the systematic instigation of water protection principles. Ahunbayev closed by emphasizing the need for the immediate implementation of all of the above recommendations. In addition to the demographic explosion, Central Asia is experiencing relatively rapid economic development, which in turn, leads to increasing water consumption. If we do not take care of it right now, it will be too late in five years' time.

With the Russian Language Waning in Central Asia, Will Other Languages Replace It?

Russian is still the most widespread foreign language in Kazakhstan, though its role is declining there, and across Central Asia in general. At the same time, the people of the region have been slow to learn other languages, in part due to economic factors such as slowing globalization, according to the Kazakhstani political analyst Zamir Karazhanov, who is head of the Kemel Arna Public Foundation. The language of cities Since declaring independence in 1991, all the counties of Central Asia have made promoting their national languages a priority. But foreign languages, which link the region with the rest of the world, have also historically been seen as critical. In practice, however, the study and use of foreign languages other than Russian is not widespread. The Russian language is losing its prominence in Kazakhstan as the number of ethnic Russians declines. According to official statistics, as of January 1, 2024, Russians made up 14.89% of the country’s population, down from close to 40% in 1989. Nevertheless, thanks to the education system and Kazakhstan’s proximity to Russia, the level of proficiency in Russian remains high. In Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, Russian is a second official language. In Tajikistan, it is called the “language of interethnic communication”. In Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan, however, it does not have an official status. More than 90% of Kazakhstanis know Russian to some degree, while 20% of the population considers it their native language. Meanwhile, those figures for Turkmenistan are 40% and 12% respectively. In Kyrgyzstan, about 44% know Russian and 5% consider it their native language; in Uzbekistan, it is about 50% and 2.7%; and in Tajikistan, 55% and 0.3%. Kazakhstan's President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev has repeatedly spoken about the need to preserve the Russian language in Kazakhstan, and the unacceptability of language-based discrimination. Last year, he unveiled the International Russian Language Organization, established by the CIS Heads of State Council. “The new organization is open to all countries and, of course, very relevant from the point of view of global humanitarian cooperation,” explained Tokayev, while underlining that measures to promote the Russian language in the Eurasia region and elsewhere are congruous with the trend of strengthening national identities. “Kazakhstan will continue the policy of bolstering the status of the state language of Kazakh,” Tokayev said at the time. Today, Kazakhstan has many Russian-language media, while Russian remains the lingua franca at meetings among post-Soviet countries. Even though Russian is concentrated in big cities, all Kazakhstanis receive a significant amount of western and other foreign news from Russian sources. “Russian is spoken in most of Kazakhstan. In the biggest city, Almaty, communicating in Russian is not a problem. But, if you move 30-50 km outside the city, it gets harder to speak it. Russian is the language of cities and the language of interethnic interaction,” the political analyst Karazhanov told The Times of Central Asia. “Of course, the number of native speakers of the Kazakh language is growing, and the number of Russian speakers is declining, but Kazakh cannot yet be the language of interethnic communication. To raise its status, large investments are still needed, including accessible, preferably free, linguistic courses so people of other nationalities can learn Kazakh. This is a long process. Historically, the Russian-speaking population did not come into contact with Kazakh, except in the provinces where mainly Kazakhs lived. Overall, across the country, the opposite process [compared to now] was taking place. Currently, geopolitical events are a factor. After the announcement of mobilization in 2022 [for Russia's war in Ukraine], migrants poured into Kazakhstan from Russia, which increased the need for Russian,” Karazhanov added. The role of slowing global growth Central Asia has slowly adopted the English language. In a global ranking of English proficiency by the language education company Education First last year, Kazakhstan ranked 104th out of 113 countries surveyed, and 22nd out of 23 in Asia, behind Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Azerbaijan. In 2022, Uzbekistan overtook its Central Asian neighbors in terms of English proficiency, though that meant just 89th place overall – its score was still considered “very low”. Meanwhile, Kyrgyzstan was ranked 91st, Kazakhstan 99th, and Tajikistan 106th. In the breakdown by city, Tashkent trailed Astana and Bishkek, which nevertheless had a low score. “The prevalence of foreign languages, including English and Chinese, which are in great demand abroad, is linked to the population’s need for them. People need these languages mainly for work, and/or to leave [Kazakhstan] to live permanently in another country. Even if the study of foreign languages goes up, this will not lead to an increase in the level of proficiency in them inside Kazakhstan, since it is linked to intentions to leave the country. For someone who [fluently] speaks a foreign language to stay in Kazakhstan, he needs a job where that language is required. In turn, the availability of such jobs mainly depends on investors who are native speakers of a foreign language, and there are not so many of them right now. Investment is rising, but we are not seeing an influx of foreign companies in which big capital would flow not to one group of industries (in particular, extractive industries), but to many groups or entire sectors of the economy at once. Chinese and English are needed in mining and the oil sector; in other areas, foreign businesses find translators, meaning this is not a mass process; the population [at large] is not included in it. In other words, a foreign language is needed either to travel abroad or to work for a foreign company, which is not very common. Therefore, the percentage of people who speak foreign languages remains low, since the population does not particularly need them for ordinary life,” says Karazhanov. Karazhanov also attributes the slow adoption of the English language in Central Asia to the lack of colonial influence in the region, meaning the language was not studied for generations. Today, he believes, the study of foreign languages is slowing, as the pace of globalization and economic growth weakens broadly, together with “people shooting all around.” In the near future, Karazhanov argues that no foreign language in Kazakhstan and in the region as a whole will be spoken proficiently by 20-30% of the population. On the contrary, if the geopolitical tensions fail to abate, the role of regional languages, including Russian, will only rise. Back to the roots Over the years, proposals have been made to add Chinese and Arabic to the compulsory study of Kazakh, Russian, and English in Kazakhstani schools, though they were never considered at the government level. Experts say interest among Kazakhstanis in learning Chinese, Turkish, Arabic, Korean, and even Uzbek (in areas along the two countries' border) is growing steadily but very slowly. The situation in Kazakhstan, Karazhanov thinks, can be extrapolated to the whole of Central Asia, though not without some reservations. “A person begins to learn a foreign language only when he faces a problem. He wants to get something, but first, he needs to learn another language. There is no such acute problem in the countries of Central Asia at this point. It is not that investors are coming, paying extra money to study [a language] and hiring huge staffs who speak Chinese or English. In terms of investment, Kazakhstan ranks first in Central Asia, so if there is no such need here, then there is definitely none in Kyrgyzstan or Uzbekistan,” the analyst noted. The situation with the Russian language varies across the region. Kazakhstan’s neighbors have always had a lower share of Russian speakers, so it is no surprise that Uzbek and Tajik are gradually becoming the lingua franca in Uzbekistan and Tajikistan. In Kazakhstan, the transition to Kazakh is also proceeding relatively painlessly, without the bumps in the road that one might expect amid such a major shift in the national makeup of the population. As for other foreign languages, Arabic is of interest as the language of the sacred texts of Islam, while Turkish has an appeal given the Turkic roots of the Kazakh language. Demand for learning them is growing steadily, explained Karazhanov, and depends less on economic and demographic factors. “I cannot say that the number of Muslims in Kazakhstan is increasing since it surged back in the 1990s, but some religious people are really trying to learn Arabic. Others are starting to learn Korean so that they can go to South Korea to work. There is a Korean diaspora in Kazakhstan, which has its own language schools, and it is not only Korean Kazakhstanis who study there. Many Kazakhstanis travel to Turkey to buy real estate. But, as I said, people must need to learn languages; if there is none, then the percentage of those who speak them will grow to some small figure and plateau there,” Karazhanov concluded.

Deadly Attacks in Russia Spark Fears of Extremism Amid Ethnic Tensions

On August 23 2024, four prison employees were killed after several prisoners staged a revolt in the remote IK-19 Surovikino penal colony in the southwestern Volgograd region of Russia. Special forces stormed the facility and “neutralized” the attackers, whom the Russian media named as Temur Khusinov, 29, and Ramzidin Toshev, 28, from Uzbekistan, and Nazirchon Toshov, 28, and Rustamchon Navruzi, 23, from Tajikistan. In a mobile phone video released by the perpetrators, the attackers identified themselves as members of Islamic State, claiming their actions were fueled by a desire to avenge the mistreatment of Muslims. The footage starkly depicted prison officials lying in pools of blood, while other clips showed the attackers moving freely through the prison courtyard. With the twentieth anniversary of the Beslan school massacre - perpetrated by members of a Chechen separatist group called the Riyad as-Saliheen Martyrs’ Brigade - drawing near, tensions in Russia are running high, with the perceived threat from extremism leading to a wave of xenophobia. The Crocus City Hall attack, which allegedly involved Tajiks, served to stoke ethnic tensions in Russia, leading to backlash by nationalists. Faced with such conditions and prejudice, an exodus of migrant workers during a time of war has left Russia with a dearth of human capital. Through the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), Russia is working with the C5 to detect and combat violent extremists, some of whom are illegally entering Central Asia before traveling to Russia. The Central Asian states, which are secular, are meanwhile trying to balance rights to religious freedom with blocking the malinfluence of oppressive and potentially violent ideologies. Three Central Asian countries border Afghanistan, and both the U.S. and the UNODC are working with Tajikistan to counter terrorism and violent extremism. While some extremist groups see Central Asia as a fertile recruiting ground, a UN report from 2023 noted that “Regional Member States estimated current ISIL-K strength at between 1,000 and 3,000 fighters, of whom approximately 200 were of Central Asian origin.” Despite these low numbers, however, the fact that some observers continue to link Islamic State Khorasan Province to the countries of Central Asia - even though the terrorist organization has purely Afghan roots - means that Central Asia once again finds itself at the center of a nexus of international security challenges.

Tajikistan Urged to Reconsider Ban on ‘Alien’ Clothing

The International Partnership for Human Rights (IPHR) has called on the Tajik authorities to repeal recent amendments to the law imposing restrictions on “foreign” clothing. According to activists, such restrictions violate international human rights, particularly the right to freedom of expression and freedom of religion. In a statement issued on August 19, IPHR emphasized that since clothing is an important element of personal identity as well as religious and cultural beliefs, states have an obligation to protect people's right to choose what they wear. According to amendments to the law “On the Ordering of Traditions, Celebrations and Rites”, enforced in June this year, Tajikistan prohibits “importing, propagandizing and selling clothes that do not correspond to the national culture.” Although a precise definition of such has yet to be provided, there has been a clear focus by authorities on “Islamic” clothing, and in particular, the issue of a fatwa by Tajikistan's Ulema Council urging women to avoid wearing “tight, black or see-through clothing.” Violations of the law are punishable by heavy fines or imprisonment for up to three years. IPHR continues to stress that restrictions based on religious, cultural, or traditional values cannot justify the violation of human rights The amendments were earlier condemned by The League of Muslim Scholars and other international organizations, and the Taliban even declared “jihad” against Tajikistan. In response to international criticism, Tajik authorities reiterated that the new law aims to protect national values and prevent extremism.

Gods and Demons of Central Asia

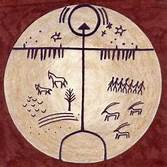

In today's dynamic world, Central Asia is emerging as a trendsetter in fashion, culture, lifestyle, and worldview. The ancient Tengrian faith, deeply rooted in Central Asian mythology and superstitions, may soon resurface creatively among the region's people, though it is unlikely to be reinstated as an official religion. While some in Kazakhstan attempt to distance themselves from Abrahamic religions, Tengrism remains a vital part of the cultural heritage, featuring gods, demigods, and dark entities that shaped the beliefs of our ancestors during the pre-Islamic era.

[caption id="attachment_22010" align="aligncenter" width="167"] photo: pininterest: Tengri's domain[/caption]

Divine entities

According to Tatar scientist and writer Gali Rahim, shamanism attributes significant roles to various spirits and deities. Among the Turkic peoples, the supreme deity is Tengri, the eternal blue sky. Rahim's lectures on “The Folklore of the Kazan Tatars,” presented at the East Pedagogical Institute in the 1920s, describe Tengri as the primary god in Turkic cosmology, with the earth and humanity emerging from the union of the sky and the earth.

Umai, the goddess associated with motherhood and children, stands next in importance. Ancient Turkic inscriptions and symbolic artifacts, such as the stone carving discovered in 2012 in the Zhambyl district of Almaty, Kazakhstan, depict her as a protective figure for children. Teleut pagans represented her as a silver-haired, young woman who descended from heaven on a rainbow to guard children with a golden bow, and the Kyrgyz appealed for her help during childbirth and when children fell ill. Motifs dedicated to Umai by Shorian shamans, were positioned around cradles. Boys' cradles were pierced with an arrow, girls' with a spindle, and wooden arrows were placed within the those of both.

Another prominent character common to Turkic, Mongolian, and Altaic mythology is Erlik or Yerlik Khan. Ruler of the underworld, the horned deity presides over the realm of the dead from a palace of black mud or blue-black iron on the bank of the Toibodym, a river of human tears. A single horsehair bridge is guarded by monsters known as dyutpa whilst the palace is protected by Erlik’s sentries or elchi, brandishing pike poles known as karmak. His breath, carried by a tan, a light warm breeze, was believed to paralyze anyone who inhaled it, which is why the Khakas term for paralysis, tan sapkhany, literally means “wind blow.”

Kudai (Khudai), also known as Ulgen, is another central deity who, alongside his brother Erlik, created the land, its vegetation, mountains, and seas. Kudai created man from clay, and Erlik gave him his soul. Kudai created a dog but it was Erlik who clothed it in hair. Whilst Kudai created the first animals, the horse, the sheep, and the cow, Erlik created the camel, the bear, the badger, and the mole. Kudai brought down lightning from the sky and commanded thunder. In a dispute over who was the mightiest creator, Kudai won. The brothers parted ways, and after producing nine sons, from whom the tribes of Kpchak, Mayman, Todosh, Tonjaan, Komdosh, Tyus, Togus, Cousin, Kerdash originate, Kudai became creator of humanity.

Demons and Evil Forces

The Turkic pantheon also includes various demonic entities. Al Basty, evil female spirits, were believed to cause illnesses and nightmares. Zhalmauyz Kempir, similar to the Russian Baba-Yaga, is a forest-dwelling creature, often described as having seven heads, few teeth and an appetite for human flesh, that preys on lost people. Zheztyrnak, a female demon with copper claws and an eagle’s beak, and Kuldyrgysh, a siren-like spirit that tickles men to death, are other fearsome figures. In Tajik and Uzbek folklore, Ajina, a goat-headed giant who lies in wait for naughty children in ash piles and empty houses, and the werewolf -like Gul Yoboni, are but two more malevolent spirits that illustrate the region's rich and diverse mythology.

This overview of Turkic mythology reveals a heritage as captivating and complex as the celebrated legends of the Mediterranean. Just as Greek mythology incorporates elements from various ancient cultures, it is possible that Turkic mythological beings have influenced other pantheons.

photo: pininterest: Tengri's domain[/caption]

Divine entities

According to Tatar scientist and writer Gali Rahim, shamanism attributes significant roles to various spirits and deities. Among the Turkic peoples, the supreme deity is Tengri, the eternal blue sky. Rahim's lectures on “The Folklore of the Kazan Tatars,” presented at the East Pedagogical Institute in the 1920s, describe Tengri as the primary god in Turkic cosmology, with the earth and humanity emerging from the union of the sky and the earth.

Umai, the goddess associated with motherhood and children, stands next in importance. Ancient Turkic inscriptions and symbolic artifacts, such as the stone carving discovered in 2012 in the Zhambyl district of Almaty, Kazakhstan, depict her as a protective figure for children. Teleut pagans represented her as a silver-haired, young woman who descended from heaven on a rainbow to guard children with a golden bow, and the Kyrgyz appealed for her help during childbirth and when children fell ill. Motifs dedicated to Umai by Shorian shamans, were positioned around cradles. Boys' cradles were pierced with an arrow, girls' with a spindle, and wooden arrows were placed within the those of both.

Another prominent character common to Turkic, Mongolian, and Altaic mythology is Erlik or Yerlik Khan. Ruler of the underworld, the horned deity presides over the realm of the dead from a palace of black mud or blue-black iron on the bank of the Toibodym, a river of human tears. A single horsehair bridge is guarded by monsters known as dyutpa whilst the palace is protected by Erlik’s sentries or elchi, brandishing pike poles known as karmak. His breath, carried by a tan, a light warm breeze, was believed to paralyze anyone who inhaled it, which is why the Khakas term for paralysis, tan sapkhany, literally means “wind blow.”

Kudai (Khudai), also known as Ulgen, is another central deity who, alongside his brother Erlik, created the land, its vegetation, mountains, and seas. Kudai created man from clay, and Erlik gave him his soul. Kudai created a dog but it was Erlik who clothed it in hair. Whilst Kudai created the first animals, the horse, the sheep, and the cow, Erlik created the camel, the bear, the badger, and the mole. Kudai brought down lightning from the sky and commanded thunder. In a dispute over who was the mightiest creator, Kudai won. The brothers parted ways, and after producing nine sons, from whom the tribes of Kpchak, Mayman, Todosh, Tonjaan, Komdosh, Tyus, Togus, Cousin, Kerdash originate, Kudai became creator of humanity.

Demons and Evil Forces

The Turkic pantheon also includes various demonic entities. Al Basty, evil female spirits, were believed to cause illnesses and nightmares. Zhalmauyz Kempir, similar to the Russian Baba-Yaga, is a forest-dwelling creature, often described as having seven heads, few teeth and an appetite for human flesh, that preys on lost people. Zheztyrnak, a female demon with copper claws and an eagle’s beak, and Kuldyrgysh, a siren-like spirit that tickles men to death, are other fearsome figures. In Tajik and Uzbek folklore, Ajina, a goat-headed giant who lies in wait for naughty children in ash piles and empty houses, and the werewolf -like Gul Yoboni, are but two more malevolent spirits that illustrate the region's rich and diverse mythology.

This overview of Turkic mythology reveals a heritage as captivating and complex as the celebrated legends of the Mediterranean. Just as Greek mythology incorporates elements from various ancient cultures, it is possible that Turkic mythological beings have influenced other pantheons.

Countries of Central Asia Team up as Threat of Natural Disasters Grows

Central Asia is vulnerable to a panoply of natural hazards: Floods, landslides, droughts, sandstorms, avalanches and earthquakes. Countries in the region increasingly seek to collaborate on early warning systems and other emergency precautions, especially since disasters can spill across borders and because the effects of climate change are intensifying. To that end, the heads of the national emergency departments of Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan met last week in Cholpon-Ata, a lakeside resort town in northern Kyrgyzstan whose attractions include ancient petroglyphs showing deer, leopards and hunting scenes. Turkmenistan´s flag – green expanse, red stripe with designs and white crescent and stars - was on display in the conference hall, though official announcements did not mention the presence of any delegation from the reclusive Turkmen government. The goal was to share information and experience, and deepen cooperation among the emergency agencies of those Central Asian countries, said Maj. Gen. Boobek Azhikeev, Kyrgyzstan’s minister of emergency situations. The five nations, which have a total of approximately 75 million people and encompass four million square kilometers, face growing risks from natural disasters, and the region has been warming faster than the global average according to a report released in May by the U.N. agency for the coordination of disaster risk reduction and the U.N. Development Programme. The two U.N. bodies, which helped to support the Central Asia meeting on the shores of Kyrgyzstan’s Lake Issyk-Kul on Aug. 15, also mentioned human-made hazards, such as industrial accidents, chemical waste facilities in densely populated areas, and severe air pollution in major cities in all the countries. “Many disaster risk management systems are still reactive, not proactive. Early warning processes are often fragmented, and poorly integrated into countries' development strategies and policies for risk-informed decision-making,” the U.N. agencies said. “There is a lack of anticipation of new and emerging risks, insufficient monitoring and forecasting, and limited financial and technological support. Early warning communication and dissemination are often unclear, especially for the most vulnerable.” The private sector and media can also get more involved in ways of reducing the risk from disasters, they said. The U.N. agencies also noted progress, saying Tajikistan had taken the lead in Central Asia in rolling out an early warning system focused on monitoring, forecasting, communication and other measures. Earlier this month TCA reported that the head of Tajikistan’s committee for emergency situations and civil defense, Rustam Nazarzada, stated that the economic damage caused by natural disasters in the country has amounted to over $12 million in this year alone. Additionally, Uzbekistan is updating an early warning system in the populous, economically important Ferghana valley that will promptly disseminate weather forecasts. Central Asian countries have sought to coordinate on environmental issues in the past, sometimes with mixed results. But the sense of urgency is growing. Earlier this year, Kyrgyzstan was among countries that sent aid to Kazakhstan after floods there that the Kazakh president described as the worst natural disaster in 80 years. Kazakhstan, in turn, sent tons of humanitarian aid to Kyrgyzstan after deadly mudflows there last month. Following the meeting in Cholpon-Ata, earlier this week powerful mudslides caused by heavy rain struck the region once again, flooding the streets of the town, causing damage across Kyrgyzstan’s Issyk-Kul region, and leading to a state of emergency being declared in three districts. Central Asia is particularly vulnerable to climate change because it is an arid area that gets much of its water from mountain glaciers, while also relying on intensive agriculture and old infrastructure amid high population growth. Another chance at regional collaboration comes next week in Tajikistan, which will host an international conference on glacier monitoring that is expected to focus on the threat of debris flows from mountainous regions.

Tajik President: Accelerated Melting of Glaciers Threatening Central Asia’s Water Resources

Over the past few decades, more than a thousand of Tajikistan’s 13,000 glaciers have completely melted—a threatening trend given that Tajikistan's glaciers are the main source of up to 60% of Central Asia’s water resources. Tajik President Emomali Rahmon announced this on August 17 at the third Voice of Global South Summit, which was held virtually under the chairmanship of Prime Minister of India, Narendra Modi. In his speech, Rahmon said that Tajikistan's initiative to declare 2025 the International Year of Glacier Preservation has received the full support of the international community. According to a UN General Assembly resolution, March 21 will be celebrated annually as World Glaciers’ Day from next year. Based on this resolution, in 2025, Tajikistan will host the International High-Level Conference on Glaciers’ Preservation. President Rahmon continued that with 93% of its territory covered by mountains, Tajikistan is considered one of the most vulnerable countries of the Global South in terms of adverse climate change impacts. Every year, the country faces floods, landslides, avalanches, and other natural disasters that cause great material damage, and, in many cases, human casualties. Earlier this month TCA reported that the head of Tajikistan’s committee for emergency situations and civil defense, Rustam Nazarzada, said at a press conference that the economic damage caused by natural disasters in the country this year has amounted to over $12 million. The government of Tajikistan is therefore implementing a National Strategy for Adaptation to Climate Change until 2030, with the goal of reducing the negative impacts of climate change on the country's social and economic spheres. Regarding green energy production, Rahmon stated that Tajikistan currently produces 98% of its electricity from hydropower. “We have decided to increase this figure to 100% by 2032, that is, to produce electricity entirely from green energy resources, and to turn Tajikistan into a ‘green country’ by 2037,” the Tajik leader stated.

Tajikistan-Kyrgyzstan Border Demarcation Completed

Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan have completed negotiations to demarcate their common border, which had been disputed for many years. The final meeting of the two countries' topographic-legal working groups was completed in the town of Batken in Kyrgyzstan on August 11-17. This has been reported by the State Committee for National Security of Tajikistan. "During this meeting, the parties continued the discussion and exchanged proposals on the description of the passage of the Tajik-Kyrgyz state border line in the remaining sections," the Committee commented. At the end of June, The Times of Central Asia reported that 94% of the borderline between Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan had been fully delineated. The conflict was caused by uncertainties regarding the exact demarcation of the border between the two republics, which spans some 980 kilometers. With its scant natural resources and dwindling water supplies, the border between Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan has been the scene of numerous armed conflicts. This situation arose after the collapse of the USSR – the parties could not agree on the ownership of dozens of disputed territories. The borderless areas have become a zone of conflict between the local population and the border troops of the other country. The last major conflict took place on September 16, 2022, as a result of which hundreds of people were killed and injured on both sides. Huge material damage was caused to the infrastructure of the border areas of the regions of Sogd (Tajikistan) and Batken (Kyrgyzstan).

Sunkar Podcast

Kazakhstan’s Return to Nuclear Power