Faced with Chinese expansion, Kazakhstan seeks alternative energy markets

ASTANA (TCA) — As China remains the major export destination for Kazakh oil and gas, Kazakhstan is seeking to diversify its hydrocarbon export routes. We are republishing this article on the issue by Farkhad Sharip, originally published by The Jamestown Foundation’s Eurasia Daily Monitor:

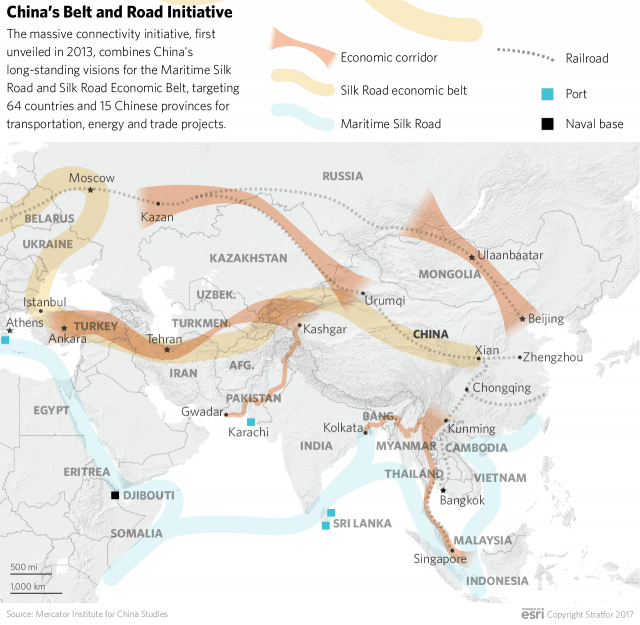

It could be assumed that the intensifying trade war between the United States and China would cause economic slowdown in China and result, in the long run, in the drastic reduction of Chinese imports of energy resources from Kazakhstan. But in his recent interview to Kazakhstani media outlets, Chinese ambassador to Astana, Zhang Hanhui, dispelled these fears. Rather, Beijing’s emissary announced that his country intends to increase imports of oil, natural gas and metals, as well as agricultural produce and raw materials from Kazakhstan. In his words, the trade war with the US will not affect in any way import volumes. He stressed the importance of the speedy implementation of the Chinese-proposed project of economic integration of states around the Altay Mountains (including Kazakhstan, China, Russia and Mongolia), as he put it, “to build a new international economic corridor” (Kursiv.kz, April 13). Such integration may arguably boost Kazakhstan’s agricultural, transport and industrial sectors. However, given Astana’s and Beijing’s substantial divergence of interests and differing export strategies, this project seems hardly feasible for the oil and gas sector.

Kazakhstan’s state-owned energy company KazMunayGaz announced its plans to export 7 billion cubic meters (bcm) of gas this year and to increase the shipment volume to 10 bcm by the year 2019. But to achieve that target, KazMunayGaz will have to increase the capacity of the Beyneu–Bozoi–Shymkent pipeline by building additional compressor stations. Apart from technical problems, KazMunayGaz is likely to face severe competition from Russian Gazprom, which is currently building its Sila Sibiri (Siberian Power) gas pipeline, from Far Eastern Yakutia to China, to ship its first annual gas supply of 38 bcm by 2019. Although, construction work on Sila Sibiri has already fallen behind schedule (Abctv.kz, January 15).

Riddled with financial and technical problems, Kazakhstan is currently unable to develop its oil infrastructure. The three pre-existing refineries, in Atyrau, Shymkent and Pavlodar, need substantial modernization. Over the last five years, the value of China’s oil and gas imports from Kazakhstan has fallen from $8.7 billion, in 2013, to $853.4 million, in 2017. Partly, this drop can be explained by the September 2013 suspension of oil output at the Kashagan oilfield, Kazakhstan’s largest oil and gas deposit, due to gas leaks in the pipeline, which took three years to replace. But a more plausible explanation evidently lies in the fact that, from 2014 on, China started importing more Russian oil through the Atasu–Alashankou pipeline, which had been used by Kazakhstan below capacity (365info.kz, February 12).

Kazakhstan is seeking to diversify its hydrocarbon export routes as an alternative to the unpredictable and politically volatile Chinese energy market. On the one hand, current political tensions between Europe and Russia as well as the sporadic threats from Gazprom to cut gas supplies to Europe encourages Kazakhstan’s KazMunayGaz in its endeavor to export its gas from Karachaganak, Tengiz and Kashagan westward via Azerbaijan. In December 2017, Kazakhstani Energy Minister Kanat Bozumbayev revealed plans of Baku and Astana to set up two working groups to implement this project (Kapital.kz, March 5).

With a European route only a hypothetical project at this point, China remains the major export destination for Kazakhstan’s oil and gas. Predictably, by the year 2020, China’s annual gas consumption will grow to 347 bcm. Kazakhstan’s hydrocarbon production has risen steeply since 2017, after the relaunch of the Kashagan oilfield, boosting its export potential. Beijing joined the Kashagan project in September, 2013, after signing an agreement between KazMunaiGaz and China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC). According to data from the Kazakhstani Ministry of Energy, in 2018 the Central Asian republic will increase its oil output by 29 percent and gas production will grow by 33.3 percent, which will allow this year’s exports to reach 17.4 billion cubic meters. But still, the planned output of 10.8 million tons of Kashagan oil is 2 million tons less than the initially targeted volume (Oilcapital.ru, February 27).

Hydrocarbon exports are of existential importance for an oil-dependent economy like Kazakhstan’s. Deputy Energy Minister Magzum Mirzagaliev said recently, at a cabinet meeting, that calls from the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) to cut oil production should not extend to Kashagan, the vital source of export revenue for the government. Kazakhstan intends to increase oil production at Kashagan from the current 215,000 barrels per day to 300,000 barrels (Kursiv.kz, April 20).

Yet, despite Kazakhstan’s need to boost exports, China is apparently finding it increasingly difficult to remain the top destination for this Central Asian country’s oil and gas as Astana looks to diversify. Meanwhile, mounting anti-Chinese sentiments in Kazakhstan following reports of political persecution of ethnic Kazakh and Uygur minorities in China further undermine closer economic ties (see EDM, January 8). At a recent government meeting, Kazakhstani foreign ministry officials, usually tight-lipped on this issue so as not to displease Beijing, promised to travel to China to familiarize themselves with the inter-ethnic situation there (Abai.kz, April 17).

Obviously, problems are not limited to growing public discontent over China’s alleged mistreatment of its Central Asian ethnic minorities. Kazakh nationalists often criticize their government for failing to limit the number of Chinese workers brought into Kazakhstan by Chinese oil companies operating in the country, which, they claim, poses a security threat. So far, Astana officials have largely ignored those calls—but for how long?