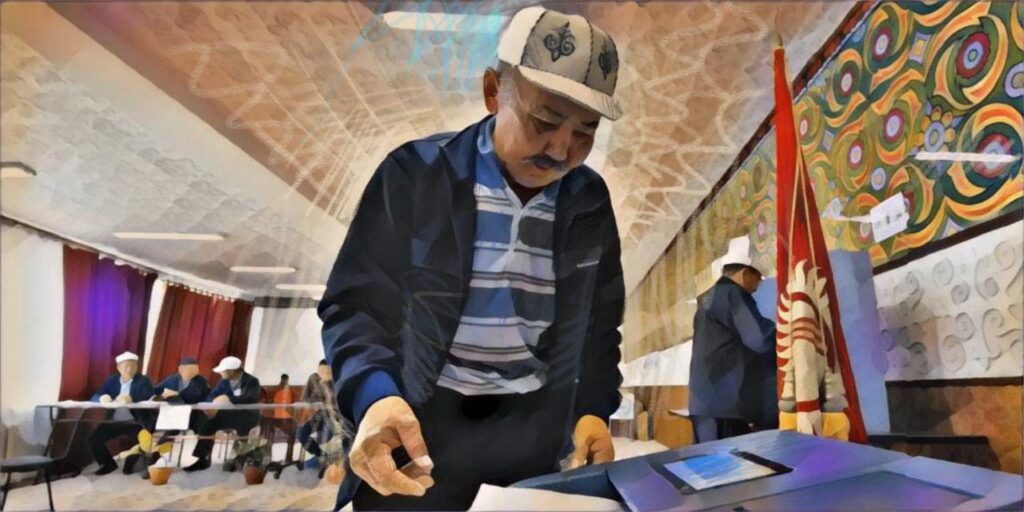

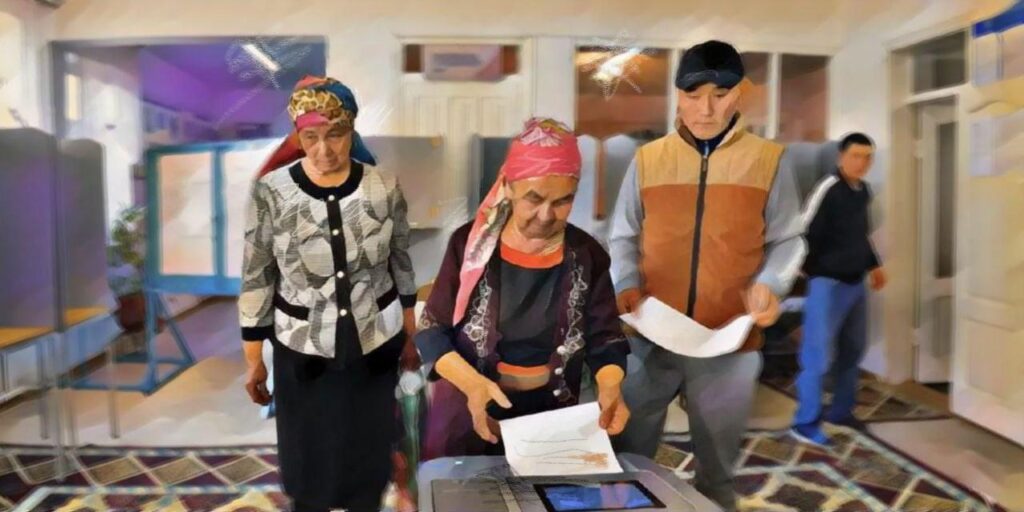

Mandatory Participation in Elections Proposed in Kyrgyzstan

On January 13, Marlen Mamataliev, a member of Kyrgyzstan's parliament, the Jogorku Kenesh, introduced a bill proposing mandatory participation in elections and referendums, along with penalties for non-participation and incentives to encourage voting. The draft legislation has been submitted for public discussion. According to the bill, all Kyrgyz citizens registered as eligible voters would be required to participate in elections. However, the proposal affirms that freedom of political expression remains protected: voters would retain the right to support any candidate or to vote “against all”, as currently allowed on the ballot. The bill outlines several exemptions. Citizens over 70 years old, those legally deemed incapacitated, individuals outside Kyrgyzstan on election day, and voters who fail to appear due to valid reasons, such as illness, natural disasters, military service, or other emergencies, would not be penalized. Proposed penalties for non-participation without a valid excuse include: A written warning for the first offense; An administrative fine for repeat violations; A temporary ban of up to five years on running for elected office or holding public service positions for systematic evasion (defined as three or more violations). The bill also proposes incentives to boost voter engagement, including discounts on state and municipal services, and awarding additional points for candidates seeking public sector employment. Notably, the legislation includes a provision for issuing a lottery ticket along with each ballot, with the Central Commission for Elections and Referendums tasked with organizing state-sponsored lotteries and prize drawings during election periods. The bill’s explanatory note highlights declining voter turnout as one of the most serious challenges facing Kyrgyzstan’s electoral system. Turnout statistics illustrate a steady drop over the past 15 years. In the 2011 presidential election, participation was 61.28%; it fell to 56.11% in 2017, and to 39.16% in 2021. Parliamentary election turnout followed a similar trend: 59.19% in 2010, 39.78% in 2015, 54.38% in the contested 2020 vote, 34.61% in 2021, and just 36.9% in the most recent parliamentary elections held on November 30, 2025. The bill’s authors point to international examples of compulsory voting, in countries such as Belgium, Australia, Turkey, Singapore, and several Latin American nations, where turnout regularly exceeds 80-90%. This initiative follows concerns voiced by President Sadyr Japarov about low voter participation in the 2025 parliamentary elections. The president addressed the issue at the fourth People’s Kurultai (National Assembly), a national forum for direct dialogue between citizens and the state, held in Bishkek in December 2025, one month after the election.