Kazakh Musicians Turn to Old Instruments to Make New Music

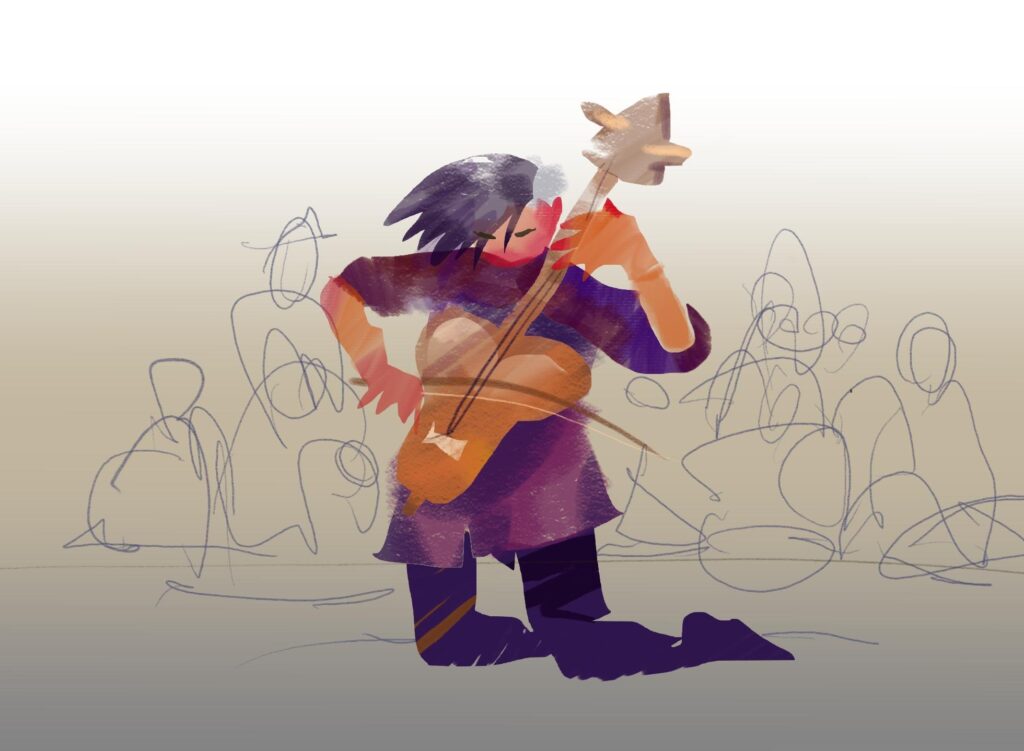

The dombra, the kyu, the kobyz, the zhetigen…. The list of traditional instruments in Kazakh music goes on. These aren’t dust-coated relics. The instruments are increasingly at the forefront of a lot of popular music in Kazakhstan today. They even get makeovers. The dombra is a long-necked, stringed instrument symbolizing Turkic culture. Now there is the electric dombra. Merey Otan, also known as Mercury Cachalot, knows about all of this. She is a musician and graduate student at Nazarbayev University in Astana and co-author of a book about the transformation of traditional instruments in Kazakhstan. In written responses to questions from The Times of Central Asia, Otan talked about contemporary Kazakh music and the role of the old instruments. After some replies, TCA includes brief explanations of her musical references. Researcher Merey Otan speaks last year at a launch for a book she co-authored about traditional instruments and contemporary music in Kazakhstan. Otan is a postgraduate student in the Eurasian Studies program at Nazarbayev University in Astana. Photo: Merey Otan Merey, tell us how you first encountered Kazakh music and what attracted you to Kazakh instruments? I have always been surrounded by Kazakh music. As long as I can remember we used to sing Kazakh folk songs at family gatherings, and various celebrations. My sister used to play dombra, a Kazakh traditional plucked two-stringed instrument, and when I started going to school I also started learning to play it. Unfortunately, I stopped taking lessons after a couple of years but I still remember how to play some compositions, kuys, and play it once in a while. TCA: Kuys is a traditional instrumental piece of Kazakh, Nogai, Tatar and Kyrgyz musical cultures. It is performed on various folk instruments. Which Kazakh instruments are considered the most popular among contemporary musicians, and why do they attract attention? Dombra is probably the most popular traditional instrument among local musicians, including contemporary ones. It also has a sacred meaning for the people in terms of national identity. This is evident in the quote of a famous Kazakh poet Kadyr Myrza Ali "A true Kazakh is not a Kazakh but a dombra." This shows that Kazakh people associate their identity with the instrument and incorporating its sound in contemporary songs allows them to situate their music in the local context. Apart from that, musicians also use instuments like qobyz, shanqobyz, zhetigen. Authenticity was always important for musicians and including traditional instruments is one of the popular strategies to demonstrate authenticity for Kazakhstan's musicians. Among the most popular examples are songs by Yerbolat Kudaibergen, Irina Kairatovna, Aldaspan, The Buhars. A dombra and a kobyz, traditional instruments used in Kazakhstan, are shown in a book that was co-authored by researcher Merey Otan. Photo: TCA TCA: The kobyz is an ancient bowed instrument preserved among the peoples of Siberia, Central Asia, the Volga region, Transcaucasia and other regions. The shankobyz is an ancient Kazakh reed musical instrument, formerly used by shaman-worshipers to...