Kyrgyz Writer Oljobai Shakir Sentenced to Five Years in Prison

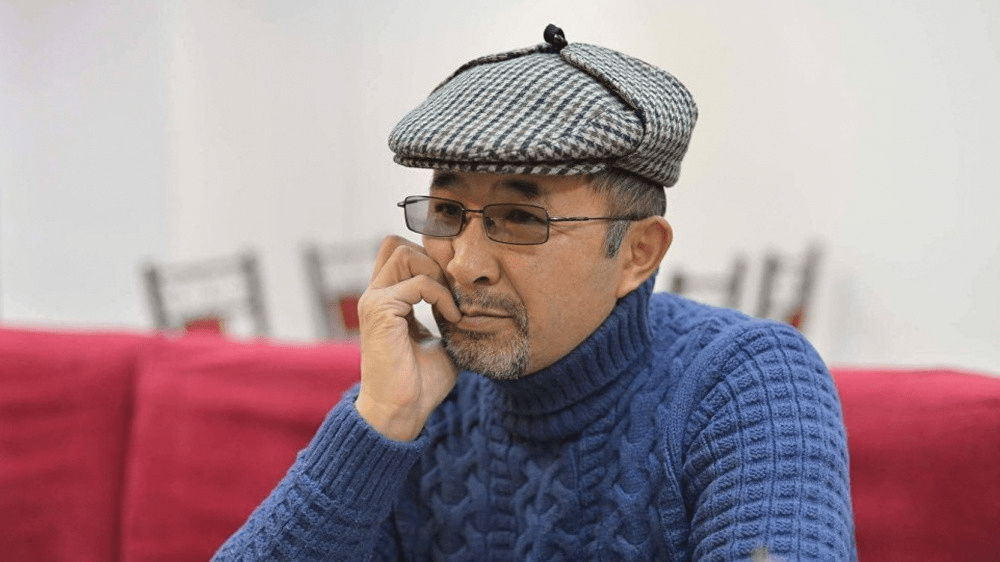

On 14 May, the Alameda District Court of the Chui Oblast in Kyrgyzstan sentenced 52-year-old activist and writer Oljobai Shakir to five years imprisonment for inciting mass riots on social media against the government. At the previous hearing, Shakir a frequent and popular blogger, pleaded not guilty to the charges of slander and argued that the aim of his posts was to encourage open dialogue between the country's leadership and its people on how the government is run. During the trial, the writer's lawyer, Akmat Alagushev, demanded the acquittal of his client and announced his intention to appeal. Olzhobai Shakir has been held in the pre-trial detention center of the SCNS since August 2023 on account of the “provocative nature” of material he posted on Facebook, TikTok and YouTube. Throughout his incarceration, the writer has denied the validity of the criminal charges against him. Renowned for his critical statements against the authorities, Shakir was arrested shortly after he had publicly scrutinized the government’s controversial transfer of four hotels on the shores of Lake Issyk-Kul to Uzbekistan. In a period when the government is increasingly clamping down on political opposition through social media, neither President Sadyr Japarov nor GKNB head Kamchybek Tashiev accepted Shakir’s invitation to be interviewed on the issue. Shakir is a well-established author and supporter of contemporary Kyrgyz literature, but like his activities on social media, his own work at times has proved highly controversial. Published in 2021 in a country where open discussion of LGBT+ rights is still taboo, his novel “Adam+” caused public outcry by relating the emotional challenges he faced during his daughter’s transgender transition.