Children in the Fields, Not at Their Desks: Turkmenistan Continues to Use Child Labor in Cotton Harvest

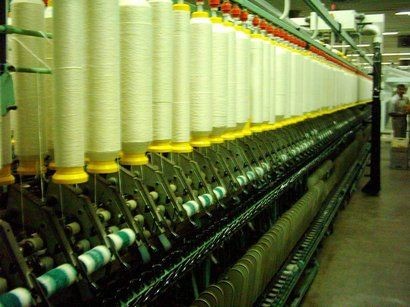

Turkmenistan continues to use forced labor of adults and children during the cotton harvest, according to experts from the Committee on the Application of Standards of the International Labor Organization (ILO). "The preliminary findings of this observation mission indicate direct or indirect evidence of mobilization of public servants in all regions visited, with the exception of the city of Ashgabat," the report by the committee states. Another report by independent Turkmen human rights groups published last year documented widespread systematic forced labor in Turkmenistan - alongside widespread corruption. Under its ILO commitments, Turkmenistan has pledged for years to eradicate this practice, but the reality is different. The Business and Human Rights Resource Center notes that the Turkmen Government obliges farmers to submit a certain quota of cotton each year. Failure to meet these quotas can result in the land being taken away from the dekhkans (smallholder farmers) and given to others, or the issuance of a fine. At the same time, the government maintains a monopoly on the purchase and sale of cotton, sets an artificially low purchase price, and does not disclose information about either the income from cotton or the use of that income. Employees of government organizations are systematically forced to harvest cotton. They are not provided with proper working or living conditions, and are often forced to find housing and food at their own expense. In addition, they face such problems as unfavorable weather conditions - cotton harvesting starts in the summer heat and continues well into winter's sub-zero temperatures - contact with chemicals used to treat the fields, and travel costs. Despite this, human rights advocates haven't received any complaints about the authorities' misconduct. This is likely due to the fact that workers are afraid of losing their jobs in the public sector, where the majority of Turkmenistan's population is employed. Despite local laws prohibiting the use of child labor - and a ban on the use of child labor in the cotton sector has been in place since 2008 - the practice is widespread during the cotton harvest. The Cotton Campaign, an international coalition of labor groups, human rights organizations, investors and business organizations, has repeatedly spoken out against this practice. Schoolchildren in Turkmenistan often go to the cotton fields themselves to earn money for clothing and food, as well as to help their parents, who are obliged to pick cotton. Turkmenistan is the tenth largest cotton producer in the world and has a vertically integrated cotton industry. Despite the boycott of cotton picked using forced labor, the U.S., Canada and EU countries cannot always control the supply chain of cotton from third countries. Thus, Turkmen cotton harvested by forced and child labor filters into global cotton supply chains at all stages of production. The Cotton Campaign has called on governments, companies and workers' organizations to take action and pressure Turkmenistan to end forced labor and protect the basic rights of its citizens. Uzbekistan is a successful case study in the effort to eliminate...