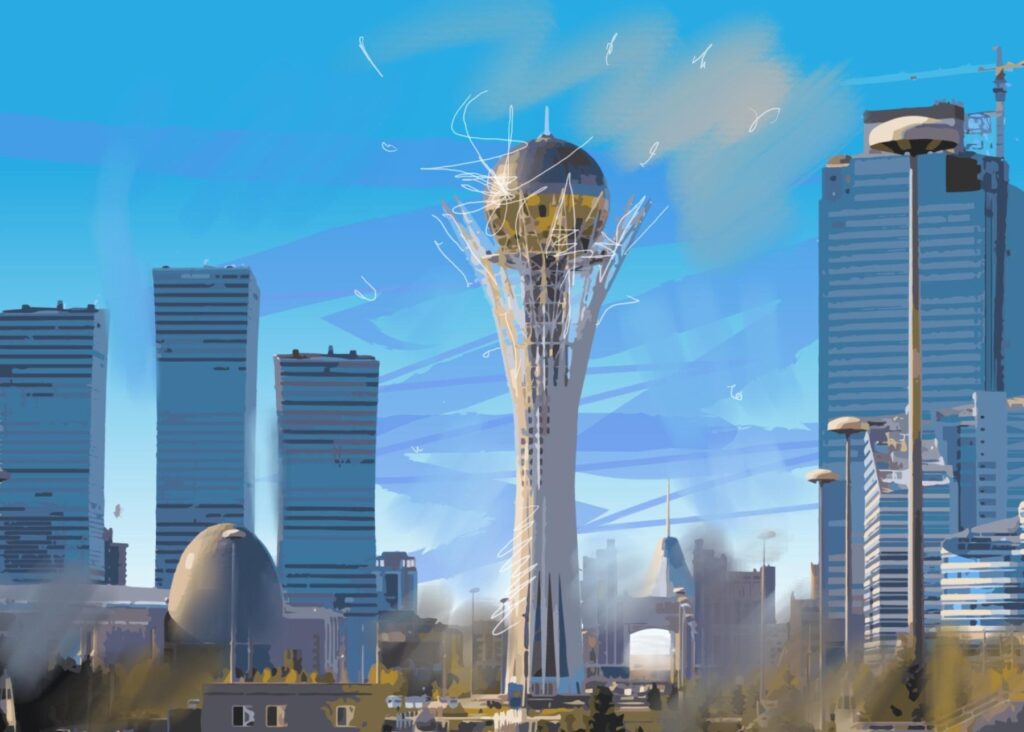

Kazakhstan: A Rising Global Player in Trade and Diplomacy

Over the past decade, Kazakhstan has become an increasingly important land-bridge between East and West, both in terms of trade and diplomacy. A vast nation the size of Western Europe with powerful neighbors in the form of China and Russia, yet on the doorstep of Europe with access to the Caspian Sea, Kazakhstan’s location has elevated it to the cusp of becoming a global power. Given its geography, it is reasonable to assert that many decisions in Kazakhstan are, out of necessity, the result of a geopolitical tightrope act necessitating a balanced and far-reaching policy outlook. This strategic position has been described by Ariel Cohen, a Nonresident Senior Fellow at the Eurasia Center of the Atlantic Council, as a “visionary multi-vector policy pioneered” by President Tokayev. Indeed, “mutually beneficially cooperation” and “mutually beneficial strategic partnership” have become watchwords of Tokayev’s presidency. Due to projects such as the Belt and Road Initiative and the Middle Corridor, Kazakhstan’s location has made it an indispensable ally to China. Playing a pivotal role in the expansion of transcontinental trade has led the whole of Central Asia to, in the words of Tokayev, “become a global stakeholder.” Trade turnover between Kazakhstan and China continues to expand, reaching $31.5 billion in 2023 (a 30% increase on 2022), and new transit routes are continuously under construction, with the Bakhty-Ayagoz railway line set to lead the opening of a third border crossing with China and increase the throughput capacity between the two nations from 28 million to around 48 million tons. Both cultural and political ties continue to grow, with a 30-day visa-free travel regime coming into force in November 2023. As for the total amount of Chinese investment in Kazakhstan over the past eighteen years, estimates vary from $23.2 to over $36 billion. Even these huge sums, however, are dwarfed in comparison to the Netherlands, which, in the last five years alone, has invested a colossal $33.8 billion in Kazakhstan. Meanwhile, according to Kazakhstan’s Bureau of National Statistics data for January to December 2022, Italy was Kazakhstan’s largest exporter, accounting for 16.4% of exports worth $13.9 billion during this period. The strength of this partnership was evinced by President Tokayev paying an official visit to Italy in January 2024, during which he held talks with Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni and spoke about the two nations’ “dynamically” developing relationship and its “enormous potential”. As a block, the EU is Kazakhstan’s biggest overall trading partner, the destination for 39% of total exports and accounting for 29.4% of its total trade in 2021. Through initiatives such as the C5+1 and the B5+1, meanwhile, the United States has increasingly sought to engage with Central Asia, and with Kazakhstan in particular. With investment totaling $19.4 billion, the U.S. ranks second in terms of foreign investment over the past five years. A driving force behind this engagement has been the huge untapped reserves of Rare Earth Elements (REEs) located in Kazakhstan. According to the Brookings Institute, whilst China is the dominant player in...