TAPI Gas Pipeline Advances Toward Herat, Afghanistan

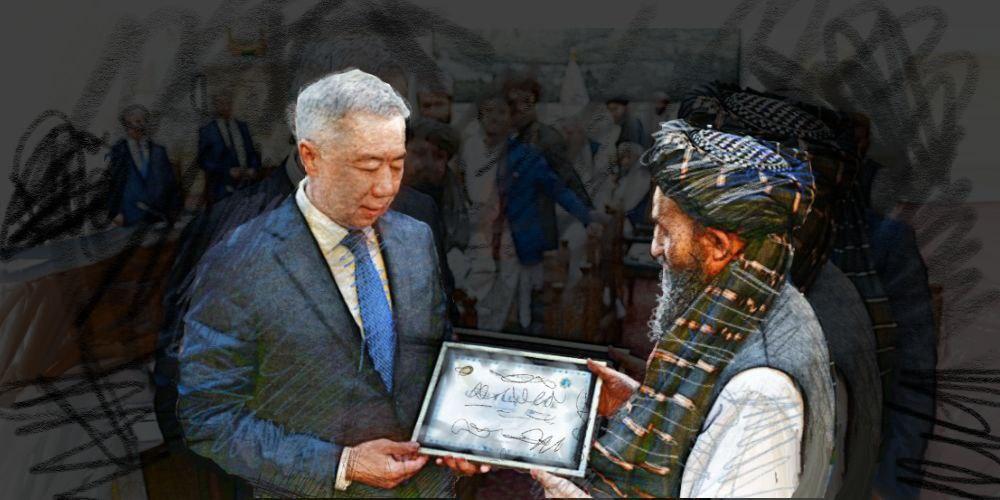

Progress on the Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India (TAPI) gas pipeline, one of the largest energy infrastructure projects in the region, was the central focus of recent talks between Turkmenistan’s Ambassador to Afghanistan, Khoja Ovezov, and Afghanistan’s Minister of Mining and Petroleum, Hedayatullah Badri. According to Turkmenistan’s state oil and gas company, Turkmennebit, the Turkmen delegation briefed its Afghan counterparts on the current phase of construction and outlined upcoming steps. Both sides expressed optimism that the pipeline will reach the western Afghan city of Herat by the end of 2026, a key milestone for the project. The TAPI pipeline is projected to span approximately 1,814 kilometers, with 214 kilometers running through Turkmenistan, 774 kilometers through Afghanistan, and 826 kilometers through Pakistan, ending at the Indian border. The Afghan segment is not only the longest outside of Pakistan but also the most challenging, both logistically and politically. The most recent development in the project, the opening of the Serhetabat-Herat section, officially named Arkadagyň ak ýoly (“Arkadag’s White Path”), was marked on October 20, 2025. Once operational, the pipeline is expected to bring substantial economic benefits to the participating countries. Afghanistan could receive over $1 billion annually in transit and related revenues, while Pakistan is projected to earn between $200 million and $250 million. These figures, according to project stakeholders, represent a significant step toward the economic goals of each nation involved. Preparatory work has already been completed on a 91-kilometer stretch of the TAPI route in Herat province. The necessary infrastructure is in place, and worker camps have been established along the pipeline corridor.