From Security Threat to Economic Partner: Central Asia’s New ‘View’ of Afghanistan

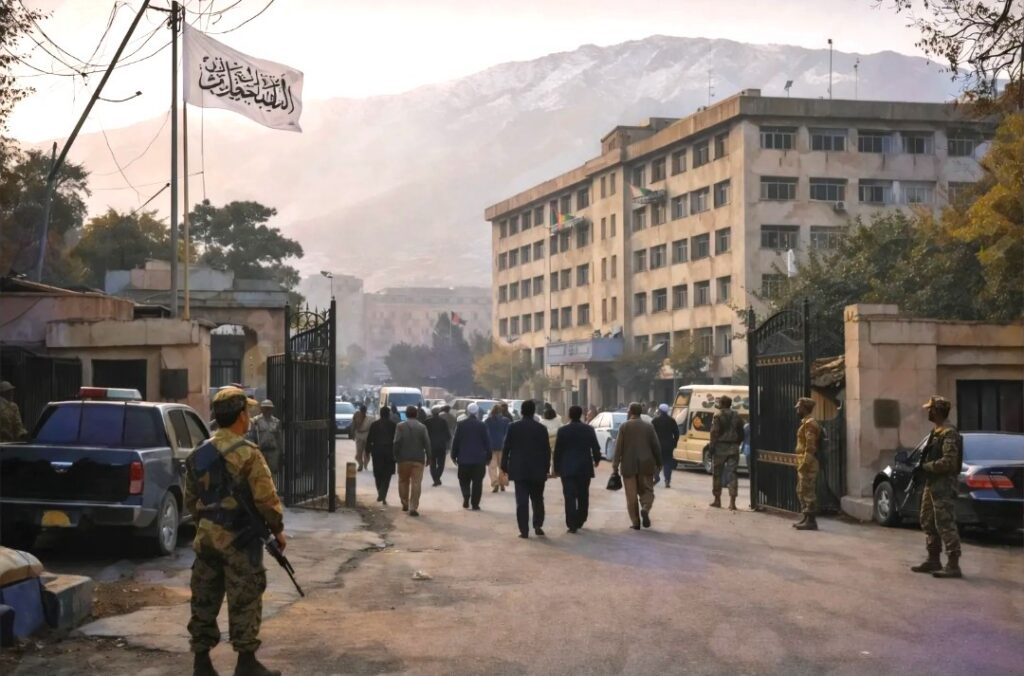

Afghanistan is quickly becoming more important to Central Asia, and the third week of February was filled with meetings that underscored the changing relationship. There was an “extraordinary” meeting of the Regional Contact Group of Special Representatives of Central Asian countries on Afghanistan in the Kazakh capital Astana. Also, a delegation from Uzbekistan’s Syrdarya Province visited Kabul, and separately, Uzbekistan’s Chamber of Commerce organized a business forum in the northern Afghan city of Mazar-i-Sharif. A Peaceful and Stable Future for Afghanistan The meeting in Astana brought together the special representatives of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan for Afghanistan. The group was formed in August 2025. There was no explanation for why the fifth Central Asian country, Turkmenistan, chose not to participate. The purpose of the Astana meeting was to coordinate a regional approach to Afghanistan. Comments made by the representatives showed Central Asia’s changing assessment of its southern neighbor. Kazakhstan’s special representative, Yerkin Tokumov, said, “In the past [Kazakhstan] viewed Afghanistan solely through the lens of security threats… Today,” Tokumov added, “we also see economic opportunities.” Business is the basis of Central Asia’s relationship with the Taliban authorities. Representatives noted several times that none of the Central Asian states officially recognizes the Taliban government (only Russia officially recognizes that government). But that has not stopped Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, in particular, from finding a new market for their exports in Afghanistan. Uzbekistan’s special representative, Ismatulla Ergashev, pointed out that his country’s trade with Afghanistan in 2025 amounted to nearly $1.7 billion. Figures for Kazakh-Afghan trade for all of 2025 have not been released, but during the first eight months of that year, trade totaled some $335.9 million, and in 2024, amounted to $545.2 million. In 2022, Kazakh-Afghan trade reached nearly $1 billion ($987.9 million). About 90% of trade with Afghanistan is exports from Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. For example, Kazakhstan is the major supplier of wheat and other grains to Afghanistan, and Uzbekistan is the biggest exporter of electricity to Afghanistan. Kyrgyzstan’s trade with Afghanistan is significantly less, but from March 2024 to March 2025, it came to some $66 million. To put that into perspective, as a bloc, the Central Asian states are now Afghanistan’s leading trade partner, with more volume than Pakistan, India, or China. Kazakhstan’s representative, Tokumov, highlighted Afghanistan’s strategic value as a transit corridor that could open trade routes between Central Asia and the Indian Ocean. Kyrgyzstan’s representative, Turdakun Sydykov, said the trade, economic, and transport projects the Central Asian countries are implementing or planning are a “key condition for a peaceful and stable future for Afghanistan and the region as a whole.” The group also discussed humanitarian aid for Afghanistan. All four of these Central Asian states have provided humanitarian aid to their neighbor since the Taliban returned to power in August 2021. Regional security was also included on the agenda in Astana, but reports offered little information about these discussions. A few days before the opening of the meeting in Astana, Russian Ambassador to Kyrgyzstan Sergei...