Kazakhstan Names First Nuclear Facility the Balkhash Nuclear Power Plant

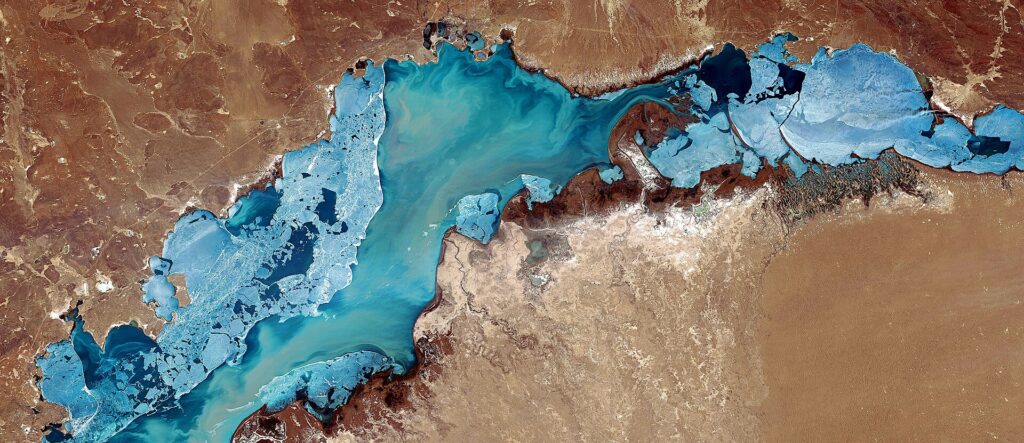

Kazakhstan has officially named its first nuclear power facility the Balkhash Nuclear Power Plant, following the results of a national competition. More than 10,000 unique names were proposed by citizens across the country, with “Balqash Atom Elektr Stansiyasy” (in Kazakh) receiving the most votes. Nationwide Contest Engages Public in Naming The competition to name the new plant was conducted via the eGov Mobile platform and ran from September 25 to October 10. Open to citizens aged 16 and older, the contest received 27,157 entries, generating 10,460 unique name suggestions. These figures accounted for variations in Cyrillic and Latin spelling, as well as synonymous formulations. A selection committee was established on September 5, comprising public figures, members of the creative sector, philologists, historians, and nuclear energy experts. In its final session, the committee reviewed the 100 most popular submissions. Why “Balqash” Was Selected The winning name, “Balqash Atom Elektr Stansiyasy,” was submitted by 882 participants, placing it at the top of the popularity ranking. The Atomic Energy Agency noted that naming nuclear power plants after their geographical location aligns with international conventions. In this case, the name references the Balkhash Lake region, where the plant is under development. The commission also approved the following official version of the name in English: Balkhash Nuclear Power Plant. Participants who proposed the winning name will receive electronic certificates of co-authorship via the eGov Mobile app within one month. Authorities have compiled a database of all name proposals, which may be used in future naming efforts for additional nuclear units or plants. Despite the public engagement, some citizens on social media questioned the outcome, expressing skepticism about the need for a contest that ultimately selected a geographically obvious name. Construction Progresses at Ulken Site While the naming contest was underway, initial construction began at the nuclear plant’s designated site near the village of Ulken in the Almaty region. Preparatory work commenced in August, led by the Russian state corporation Rosatom as the general contractor. By the end of October, design and survey work was already in progress. The Ulken Nuclear Power Plant is expected to play a central role in Kazakhstan’s long-term energy strategy. Discussions are also underway regarding a potential second nuclear facility in the Zhambyl District of the Almaty region, though this project remains in the evaluation phase. Experts consider the area a promising location for future development.