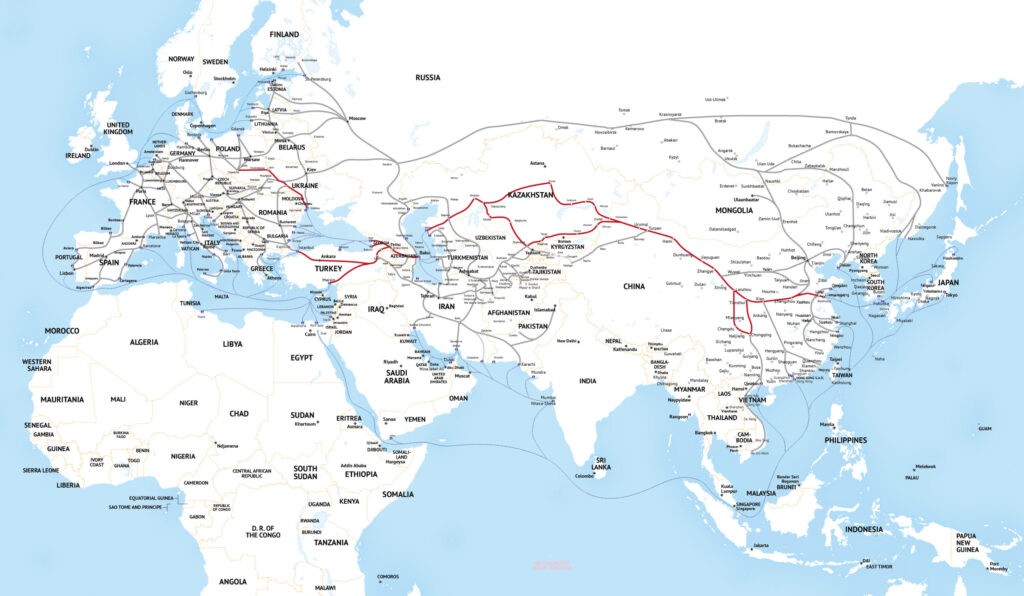

The challenging geopolitical situation in the region, combined with sanctions pressures, has ruptured traditional transport and logistics chains. Finding itself sandwiched, Kazakhstan has had to actively build new routes for transportation and freight, and to diversify its own suppliers. Measures previously taken to develop the transport and logistics industry has made it possible to solve these problems to some extent, though it still faces many challenges ahead. Kazakhstan’s transport and logistics industry plays an important role in the country’s economy and attracts cargo flows. To transform the country into a transport and transit hub – one of the government’s declared strategic objectives – a number of large-scale measures are being taken today, with investments in the industry of about KZT1.8 trillion (U$4 billion), which are already bearing fruit. Last year, about 29 million tons of freight passed through Kazakhstan, up 21% year-on-year, the lion's share of which was transported by rail. Indeed, railways are slated to lead the country’s transit development. To further increase cargo flow, boost efficiency and, most importantly, expand the capacity of railroads, three large-scale projects were launched in Kazakhstan last year: the construction of a railway line bypassing the Almaty station, as well as two other lines – Darbaza-Maktaaral and Bakhty-Ayagoz. Over the next three years, more than 1,300 km of new rail lines will be laid. The projects aim not only at increasing transit traffic through Kazakhstan, but also expanding the country’s export potential and removing existing bottlenecks. Besides modernizing infrastructure, the industry faces many other tasks to spur transit traffic, including updating rolling stock, putting in place modern digital services, establishing competitive tariff rates for the transport of transit freight, etc. To support cargo flows by road, the most used option, the construction and reconstruction of federal and local highways continues. In 2023, over 10,000 km of road was built or repaired. Such large projects as the BAKAD (Almaty ring road) and the Kandyagash-Makat and Usharal-Dostyk highways were completed. In the coming years, several road projects along federal and regional networks are planned, comprising a total length of about 9,000 km. More attention is to be paid to the quality of the roads under construction, which has been known to raise questions among motorists. Kazakhstan’s maritime transport industry has also seen much development. In this regard, in the near future the creation of a container hub is planned at the Aktau seaport, along with the reconstruction of its docks and an upgrade of handling equipment. Dredging work is also to be done. The port of Kuryk is also being developed through the construction of a multi-functional terminal. Taken together, this will boost the throughput capacity of Kazakhstan’s seaports by 10 million tons, with container capacity rising to 300,000 TEUs per year. This is especially important in the context of the active development of alternative trade routes, in particular the Trans-Caspian International Transport Route (TITR) and the International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC), for which both seaports will be used. The potential of these routes is...