“A Road Not for the Faint-Hearted”: How Austrian Prisoners of War Built a Tourist Path in East Kazakhstan

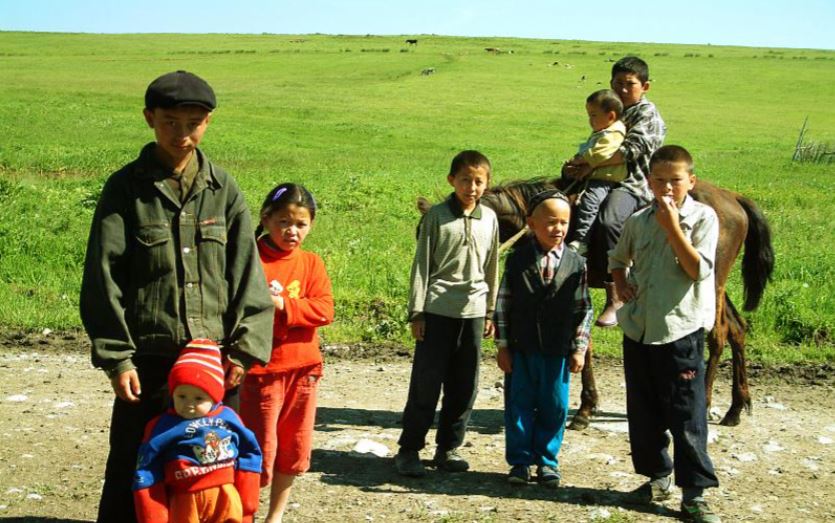

A winding mountain road in East Kazakhstan has become a point of fascination not only for tourists but also for historians, filmmakers, and researchers. Known variously as the Old Austrian Road, the Austrian Route, or Irek Zhol (“Winding Road”), this nearly 50-kilometer path connects the Katon-Karagai and Markakol districts, cutting through pristine wilderness in a national park and a state reserve. Today the path is being restored, but the road’s true value lies in a dramatic and little-known past that stretches back over a century. A New Chapter for an Old Road In July 2025, authorities announced the launch of extensive repair work on the Old Austrian Road. With a budget exceeding $1 million from the regional government, the project includes rebuilding a damaged bridge near Katon-Karagai, replacing culverts, reinforcing slopes, and rehabilitating impassable sections. The most challenging terrain lies near Lake Markakol, where the route crosses swampy stretches, sharp switchbacks, and granite outcroppings. Yet these obstacles have not deterred growing numbers of visitors, off-road enthusiasts, cyclists, hikers, and even horse riders, eager to explore the wild beauty of Eastern Kazakhstan. [caption id="attachment_35993" align="aligncenter" width="1280"] Image: TCA/Yulia Chernyavskaya[/caption] The Road’s Origins in War and Captivity Though few know it, this scenic mountain route has deep strategic and historical roots. Long before the 20th century, locals used it as a trail for horses and carts. But by the early 1900s, the Russian Empire decided to formalize the path, partly due to the road’s proximity to the Chinese border. Between 1914 and 1916, the road was reconstructed, largely by Austrian prisoners of war, mainly ethnic Czechs, Slovaks, Hungarians, and Galicians, captured during World War I. According to Vienna-based historian Lana Berndl, who has conducted extensive research on the topic, roughly 800 prisoners were transported from Austria via St. Petersburg and Omsk to the Irtysh River and then forced to march to the village of Altai (now Katon-Karagai). Around 600 reached their destination. Construction began simultaneously from Katon-Karagai and Alekseevka. Despite working only in the warmer months, the prisoners built a road whose difficulty rivals Alpine passes. During the harsh winters, many worked on local farms and integrated into village life. Some even married and remained in Kazakhstan permanently. [caption id="attachment_35994" align="aligncenter" width="1280"] Image: TCA/Yulia Chernyavskaya[/caption] Tragically, several were later repressed during Stalin’s purges. Among them was Ludwig Fritzen, a Hungarian prisoner who stayed, married a local woman, and was executed in 1937 after being accused of espionage. Remnants of this history remain: roughly 30 graves with Gothic-scripted crosses can still be found in old cemeteries throughout the region, silent testimonies to those who built the road under extreme duress. Film Rekindles Forgotten History In 2016, Austrian filmmaker Ruslana Berndl released a documentary titled The Austrian Road, which brought global attention to the forgotten story. She first learned about the road from a brief mention in a German travel guide that described it as “not for the faint-hearted” and built by Austrian POWs. Intrigued, Berndl, then a doctoral student at the University of...