The Language Nobody Wants to Speak About: Russian’s Uneasy Place in Central Asia’s Cultural Conversation

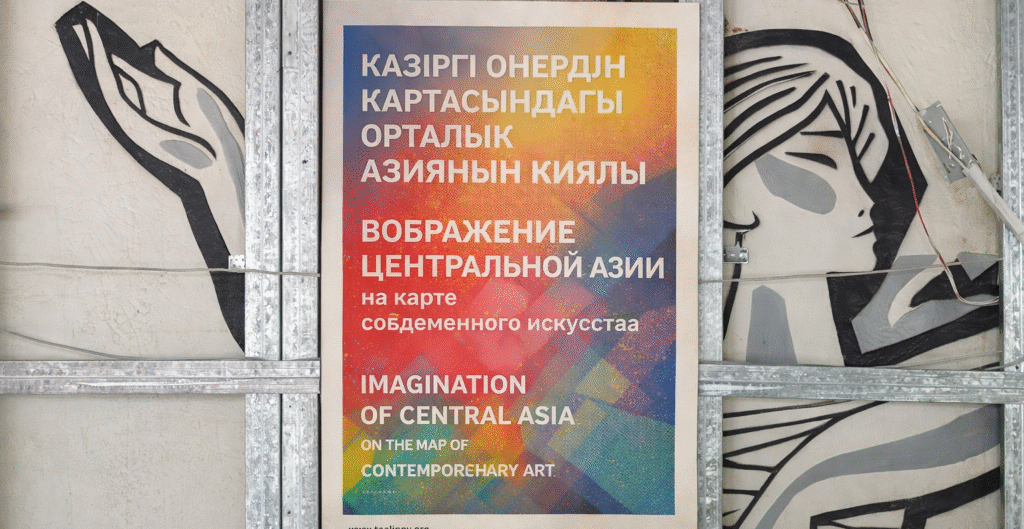

Rhetoric in segments of the Russian media has sharpened debates over sovereignty and influence across Central Asia, pushing these concerns beyond policy circles and into everyday conversations. The region is reassessing not only pipelines and alliances, but language itself. In politics, this shift is visible and symbolic. In culture, it is more difficult to discern. The Russian language still shapes how Central Asian art is funded, circulated, and institutionally processed, even as institutions distance themselves from Moscow’s influence. This contradiction sits at the heart of contemporary cultural life in the region. Artists produce work rooted in Kazakh, Uzbek, Kyrgyz, Tajik, or Turkmen histories. They title exhibitions in local languages. They speak passionately about decolonial futures and cultural sovereignty. But when the catalogue is written, the grant application submitted, or the curatorial text sent abroad, the language quietly shifts. First to Russian, sometimes to English, and only occasionally does it remain in the local language. This is not nostalgia, but a structural inheritance. Russian remains the shared professional language of much of the urban cultural sector. Edward Lemon, President of the Oxus Society for Central Asian Affairs, argues that the language’s endurance reflects both ideology and pragmatism. “While local languages have become much more widespread as the Central Asian republics have strengthened their nationhood and as there has been an increase in anti-Russian sentiments since the invasion of Ukraine, Russian language use remains widespread,” Lemon told TCA. “Despite the ideological imperative to reduce reliance on Russian, there are some pragmatic reasons why it remains prominent. High levels of migration to Russia, particularly from Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Kazakhstan, mean that a basic competence in the language is essential to survival for many Central Asians. Russian remains a language of interethnic communication, particularly in Kazakhstan, where ethnic Russians, for the most part, are reluctant to speak Kazakh. While English has become more widespread and some of the Central Asian languages are mutually intelligible, Russian retains a status as a diplomatic, business, and civil society language for those working in multiple countries. Russia also remains a language of education. Over 200,000 Central Asians study in Russia, by far the largest destination in the world. Russian-language schools remain prominent at every level in Central Asia, from kindergarten to graduate schools. In short, while the usage of Russian is in slow decline, its position is relatively entrenched.” For cultural institutions, this reality means that distancing from Moscow politically does not automatically sever the linguistic infrastructure through which grants are written, exhibitions travel, and contracts are signed. Naima Morelli, an arts writer focused on contemporary art across Asia-Pacific and the Middle East, argues that the issue is less about elimination than coexistence. “For me, it makes sense that Russian continues to function as a practical operating language across Central Asia’s cultural infrastructure, as an inherited connective tissue of sorts. In the hypothesis of getting rid of it, the most obvious alternative for a shared language for exchanges across countries in Central Asia is English, which the global...

22 hours ago