Kazakhstan-Singapore Center for Quantum Technologies Opens at Farabi University

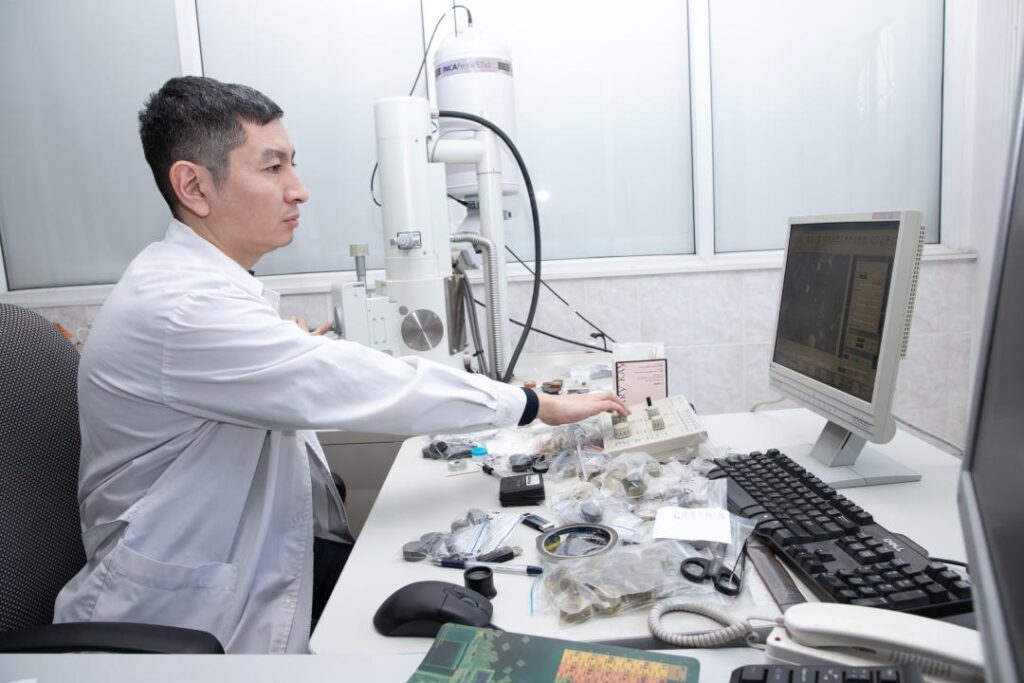

The Kazakhstan-Singapore Center for Quantum Technologies has been inaugurated at Al-Farabi Kazakh National University in Almaty. The project, implemented in partnership with Singapore-based ASTRASEC PTE. LTD and Qubitera LLP, aims to serve as a foundation for developing a national quantum technology ecosystem in Kazakhstan. According to the Ministry of Science and Higher Education, the center will focus on both fundamental and applied research, the training of researchers, engineers, and technology entrepreneurs, and the development of quantum-secure communication and computing solutions. It also plans to facilitate the transfer of advanced international expertise and support the creation of joint technology startups. The first phase of the project includes the launch of a laboratory dedicated to quantum cryptography and quantum communications. The facility is equipped with photonic systems and experimental infrastructure intended for research and specialist training. At the opening ceremony, Minister of Science and Higher Education Sayasat Nurbek said that the world is entering what he described as a “quantum revolution,” noting that traditional silicon-based digital and computing technologies are approaching their practical limits. He stated that the establishment of the center creates new opportunities for the development of Kazakhstan’s scientific and technological capacity. KazNU Rector and Chairman of the Board Zhanseit Tuimebayev emphasized the importance of integrating academia and industry, describing the center as part of the university’s strategy to transform into a research-oriented institution of international standing. He said cooperation with Singaporean partners would help combine academic expertise with advanced technological experience. Zhang Yinghua, Chairman of the Board of Directors of ASTRASEC PTE. LTD, described the development of quantum technologies as strategically important for national information security and digital resilience, highlighting quantum communication as a growing global priority. The inauguration concluded with a roundtable discussion focused on the center’s future development, quantum cybersecurity, industrial partnerships, and intellectual property protection for joint projects.