Unbent, Unbowed, Unbroken: The Art of Saule Suleimenova

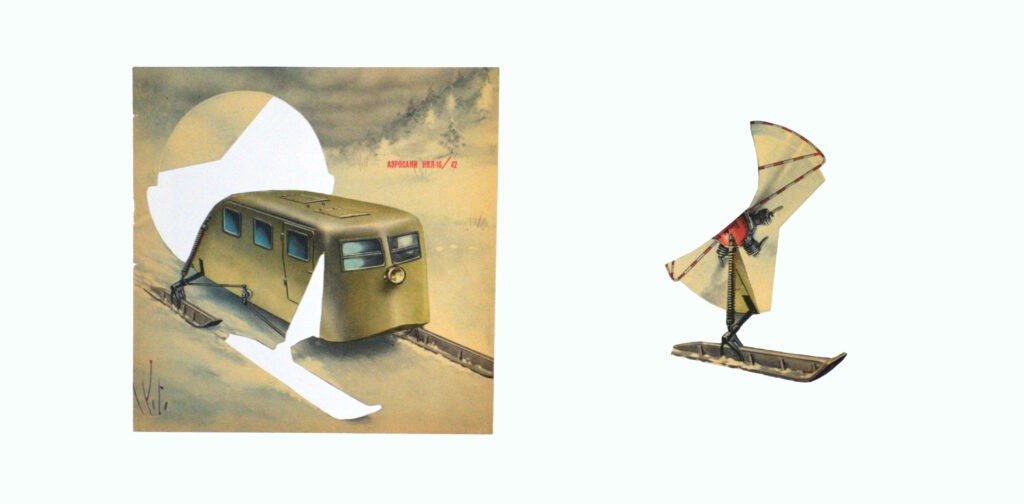

“I’m a very emotional person,” says artist Saule Suleimenova with a bright, open laugh from her home studio in Almaty. Widely recognized as one of the most significant Kazakh artists working today, Suleimenova’s spontaneity and passion emerge clearly as the artist lightens up when talking about the joy and necessity of making work, when she excavates memories of the early days of making art, or when suddenly, she grows gloomy, remembering some of the most painful moments in the history of her country. Behind her back stands a large canvas, where translucent elements, almost resembling stained glass from a distance, slowly reveal themselves as fragments of discarded plastic bags fused together through heat and a whole lot of patience. Born in 1970, Suleimenova has developed a practice that spans painting, drawing, photography, and public art, consistently navigating the delicate and often hard to define boundary between personal memory and collective history: “I feel my personal life can’t be detached from politics and everything that happens around me,” she says, embodying, in a way, a motto from the seventies: “the personal is political.” Suleimenova was an early member of the Green Triangle Group, an experimental artist collective known for its avant-garde and punk-influenced art, which emerged during the Perestroika era and the collapse of the USSR, playing a significant role in revolutionizing contemporary art in Kazakhstan. Today, she is working mostly with archives, vernacular imagery, and the visual language of contemporary urban space. In her work, she investigates how narratives are formed, distorted, and even rewritten over time, particularly within the historical and political context of Kazakhstan. An example is her ongoing series, Cellophane Paintings, composed entirely from used plastic bags, transforming everyday waste into luminous, layered pictorial fields that hold together subjects as vast as socio-political trauma, from the Kazakh famine of 1930–1933, human rights violations, Karlag, one of the largest Gulag labor camps, and the Uyghur genocide. Those heavy themes are associated with some that are more intimate: family members, flowers, and cityscapes. Suleimenova is currently participating in the Union of Artists at the Center of Modern Culture Tselinny in Almaty (15 January – 19 April 2026), curated by Vladislav Sludsky, an exhibition reflecting on artistic partnerships as systems of survival in a region where art historically survived through shared spaces and personal alliances between artists, rather than institutional support. The Times of Central Asia spoke to Suleimenova about memory, material, and the ways personal experience and political history converge in her art. [caption id="attachment_42718" align="aligncenter" width="2500"] From the series, One Step Forward[/caption] TCA: Your recent work at the Bukhara Biennial, Portraits of the people of Bukhara, was made from polyethylene bags collected by the community itself. Can you tell me how your work on this project took shape? Suleimenova: From the beginning, the work was meant to be collaborative with local artists or artisans rather than something already finished and brought from outside. I decided to collaborate with a folk ensemble of Bukhara women - the retired performers...