The Ruthless History of the Great Game in Central Asia

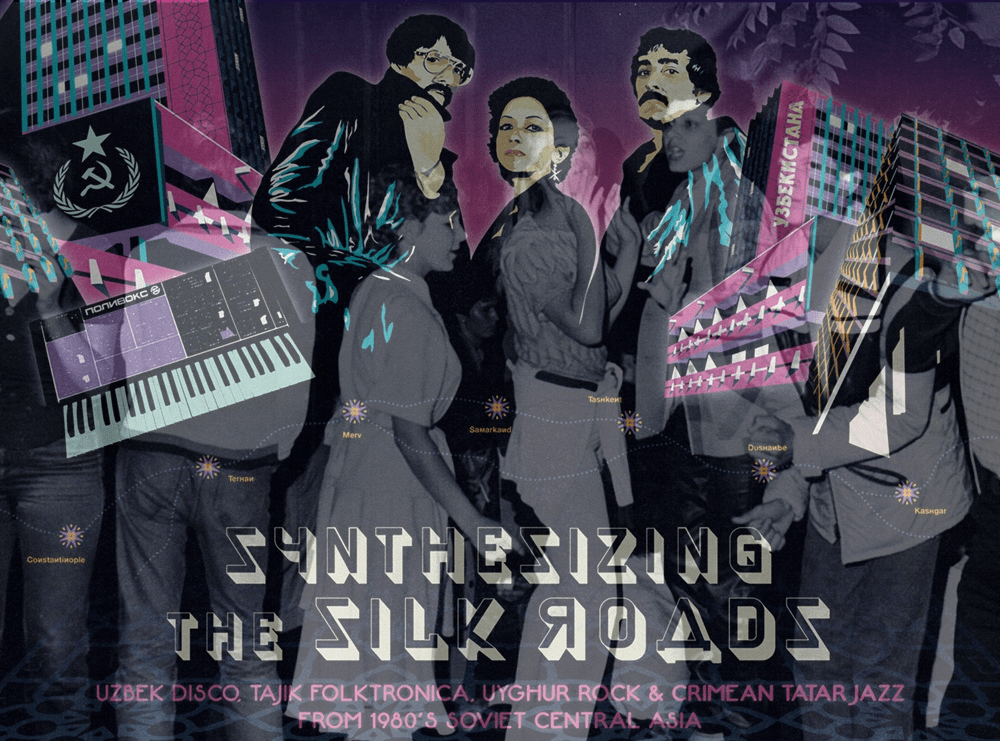

In the so-called New Great Game, Central Asia is no longer a mere backdrop; with its strategic location, massive oil and gas reserves, and newfound deposits of critical raw materials, it’s a key player. In stark contrast to events in the 19th century, this time, Central Asia finds itself courted by four great powers - China, the EU, the U.S., and Russia - instead of caught in the crosshairs of conquest. The region finds itself with agency. However, the original Great Game was anything but fair play. Comprising vast steppes, nomadic horsemen, descendants of Genghis Khan’s Great Horde, and a lone nation of Persians, during the 19th century, the once-thriving Silk Road states became entangled in a high-stakes battle of expansion and espionage between Britain and Russia. Afghanistan became the buffer zone, while the rest of the region fell under Russian control, vanishing behind what became known as the “Iron Curtain” for almost a century. The term “Great Game” was first coined by British intelligence officer Arthur Conolly in the 19th century, during his travels through the fiercely contested region between the Caucasus and the Khyber. He used it in a letter to describe the geopolitical chessboard unfolding before him. While Conolly introduced the idea, it was Rudyard Kipling who made it famous in his 1904 novel Kim, depicting the contest as the epic power clash between Tsarist Russia and the British Empire over India. Conolly’s reports impressed both Calcutta and London, highlighting Afghanistan’s strategic importance. Britain pledged to win over Afghan leaders — through diplomacy, if possible, and by force, if necessary. The Afghan rulers found themselves caught in a barrage of imperial ambition, as the British and Russian Empires played on their vulnerabilities to serve their own strategic goals. Former Ambassador Sergio Romano summed it up perfectly in I Luoghi della Storia: "The Afghans spent much of the 19th century locked in a diplomatic and military chess match with the great powers — the infamous 'Great Game,' where the key move was turning the Russians against the Brits and the Brits against the Russians." The Great Game can be said to have been initiated on January 12, 1830, when Lord Ellenborough, President of the Board of Control for India, instructed Lord William Bentinck, the Governor-General, to create a new trade route to the Emirate of Bukhara. Britain aimed to dominate Afghanistan, turning it into a protectorate, while using the Ottoman Empire, Persian Empire, Khanate of Khiva, and Emirate of Bukhara as buffer states. This strategy was designed to safeguard India and key British sea trade routes, blocking Russia from accessing the Persian Gulf or the Indian Ocean. Russia countered by proposing Afghanistan as a neutral zone. The ensuing conflicts included the disastrous First Anglo-Afghan War (1838), the First Anglo-Sikh War (1845), the Second Anglo-Sikh War (1848), the Second Anglo-Afghan War (1878), and Russia’s annexation of Kokand. At the start of the Central Asian power struggle, both Britain and Russia had scant knowledge of the region's people, terrain, or...

1 week ago