On January 18th, the European Parliament adopted a resolution on human rights in Tajikistan which condemns the ongoing crackdown against independent media, government critics, human rights activists and independent lawyers, as well as the closure of independent media and websites.

Parliament members urged the authorities to stop persecuting lawyers defending government critics and journalists, and immediately and unconditionally release those arbitrarily detained and drop all charges against them, including human rights lawyers Manuchehr Kholiknazarov and Buzurgmehr Yorov.

In the resolution, the European Parliament members insisted that respect for freedom of expression in Tajikistan should be taken into account when assessing the application of the EU’s Generalised Scheme of Preferences (GSP+) for Tajikistan and negotiations of a new EU-Tajikistan Partnership and Cooperation Agreement.

In December 2023, the chair of the U.S. Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, Ben Cardin sent a letter to the President of Tajikistan, Emomali Rahmon, urging him to cease acts of domestic and transnational repression against political opponents and religious minorities. “There are persistent reports of arbitrary arrest, denial of judicial due process, as well as acts of violence including torture, assault and even instances of murder of journalists, political dissidents, as well as community and religious leaders,” Cardin wrote.

In recent years, several Tajik journalists, activists, and opposition politicians have been sentenced to lengthy prison terms largely based on accusations of collaborating with organizations labelled as extremist or banned in Tajikistan.

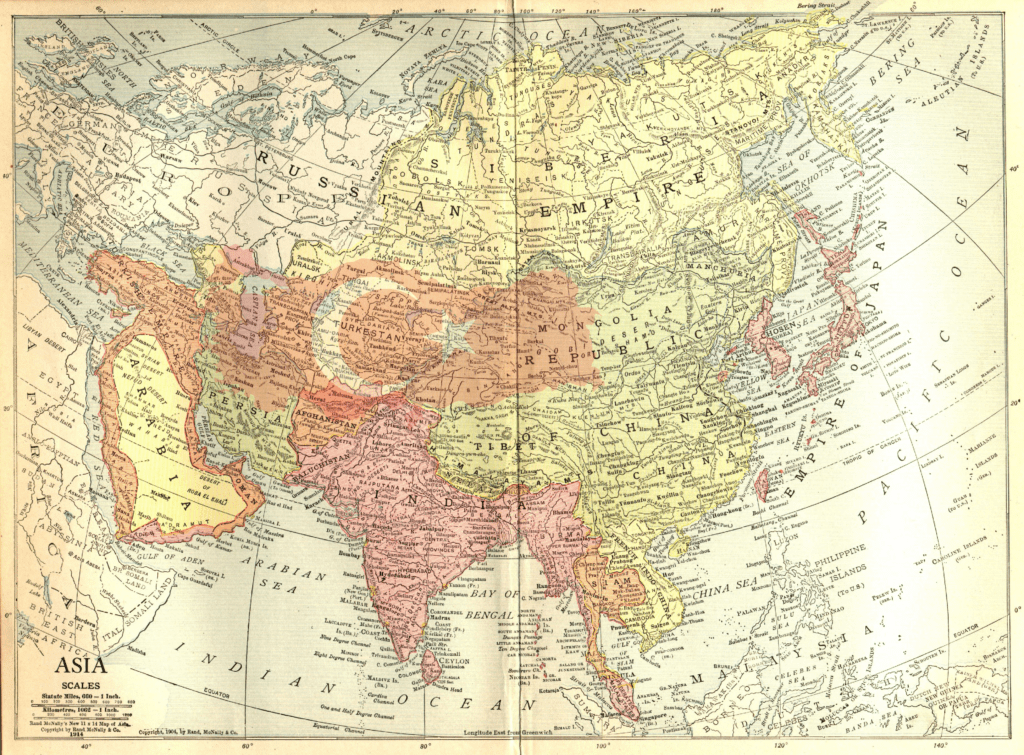

Still a relatively young country, the official date of the independence of Tajikistan – a front-line state facing the extremism of the Taliban – is September 9th 1991. Whilst criticisms are warranted and accurate, particularly through the prism of western democracy, the crux of the problem would appear to be endemic corruption and weak institutions propagated by kleptocratic wealth and organized crime.

As to how high up the criminality goes, in 2000 the Tajik Ambassador to Kazakhstan was arrested in Almaty with 86 kilos of heroin in his car. In 2001, the Deputy Minister of the Interior was murdered, the prosecution in the case arguing he’d been assassinated for refusing to pay for a shipment of 50 kilos. A statement released by the UNDP in 2001 estimated that drug money accounted for between 30 -50% of the Tajik economy.

The year Tajikistan took over policing of its border with Afghanistan from the Russians, seizures of heroin halved. Piqued by the critical international response, President Rahmon levelled counter-allegations of Russian complicity in the heroin trade. “Why do you think generals lined up in Moscow all the way across Red Square and paid enormous bribes to be assigned here?” he complained to U.S. officials. “Just so they could do their patriotic duty?”