The moon landing is imprinted on the Western collective psyche, but Baikonur is not. Like most children growing up in the U.S., I watched William Shatner on Star Trek, and when we think of space, we think of Neil Armstrong and NASA, not Kazakhstan. However, on April 12, 1961, the first man in space, Yuri Gagarin, took off from the Baikonur Cosmodrome in what is now Kazakhstan. Like WWII, however, space is the subject of parallel narratives, and the “Space Race” was an integral part of the Cold War.

Baikonur Is a Place of Firsts

Baikonur is a place of firsts – the first artificial satellite, Sputnik 1, the first dog, Laika, the first higher living organisms to survive a journey to outer space, Belka and Strelka, the first man, Yuri Gagarin, and the first woman, Valentina Tereshkova, all took off from Baikonur. Originally constructed during the Cold War as a missile test site, the area was chosen for several reasons; it’s isolation from densely populated areas and proximity to the equator made it easier to launch rockets, and the flat landscape ensured radio signals would not be disrupted.

The battle for control over space between the U.S. and the Soviet Union was both ideological and military in nature. Baikonur was baptized in Cold War misinformation tactics. Located thirty kilometers south of the launch facilities, the closest town was originally known as Tyuratam. In 1961, Soviet officials swapped its name with a town located some 350 kilometers away, “Baikonur,” to misdirect Western intelligence. A fake spaceport constructed from plywood was erected in the “real” Baikonur to deceive enemy spy planes.

In the early 1960s, the Soviet Union’s covert actions allowed it to advance its space program faster than the United States, which faced public and media scrutiny. While U.S. space missions were broadcast live, exposing any failings, the USSR could operate clandestinely, protecting its missile technology and maintaining a strategic edge. A key example is the R7 rocket used to launch Yuri Gagarin into space; the largest intercontinental ballistic missile of its time, its details were closely guarded.

Fifty year commemorative stamp of the first woman in space, Kazakhstan, 2013

“Space Race” Propaganda

Another tool of Cold War propaganda was the flight of Valentina Tereshkova, the “First Lady of Space.” Prior to her journey to the stars in June 1963, Tereshkova had worked on an assembly line in a textiles factory. Her parachuting experience with a local paramilitary flying club proved crucial in her selection. In her three-day flight, the every-woman clocked up more space hours than all American astronauts up to that time combined. Tereshkova may have been a propaganda tool dispatched for Western audiences as proof of gender equality in the USSR, but it would be a nineteen year wait for the next female cosmonaut.

In 2007, at the age of seventy, Tereshkova volunteered for a one-way mission to Mars. Having turned to politics as her primary concern following her spaceflight, in March 2020 she moved an unannounced but obviously stage-managed amendment in the State Duma which could keep Vladimir Putin in office until 2036.

Upon the fall of the Soviet Union, the Russian authorities negotiated with Kazakhstan to keep using the spaceport. Officially Russian territory on Kazakh soil, today Putin appoints the mayor of Baikonur, which is leased out at an annual rate of a $150 million. Still home to Russian launches, in 2005 the Kazakh government signed a new deal allowing their neighbor to stay until at least 2050. “We would like Russia to stay at Baikonur forever,” former cosmonaut and current Director of the Aerospace Agency of Kazakhstan, Talgat Musabayev declared at the time. Relations have not been so rosy recently, however. In 2023, Kazakhstan impounded the spaceport over Roscosmos’ unpaid debts of $29.7 million.

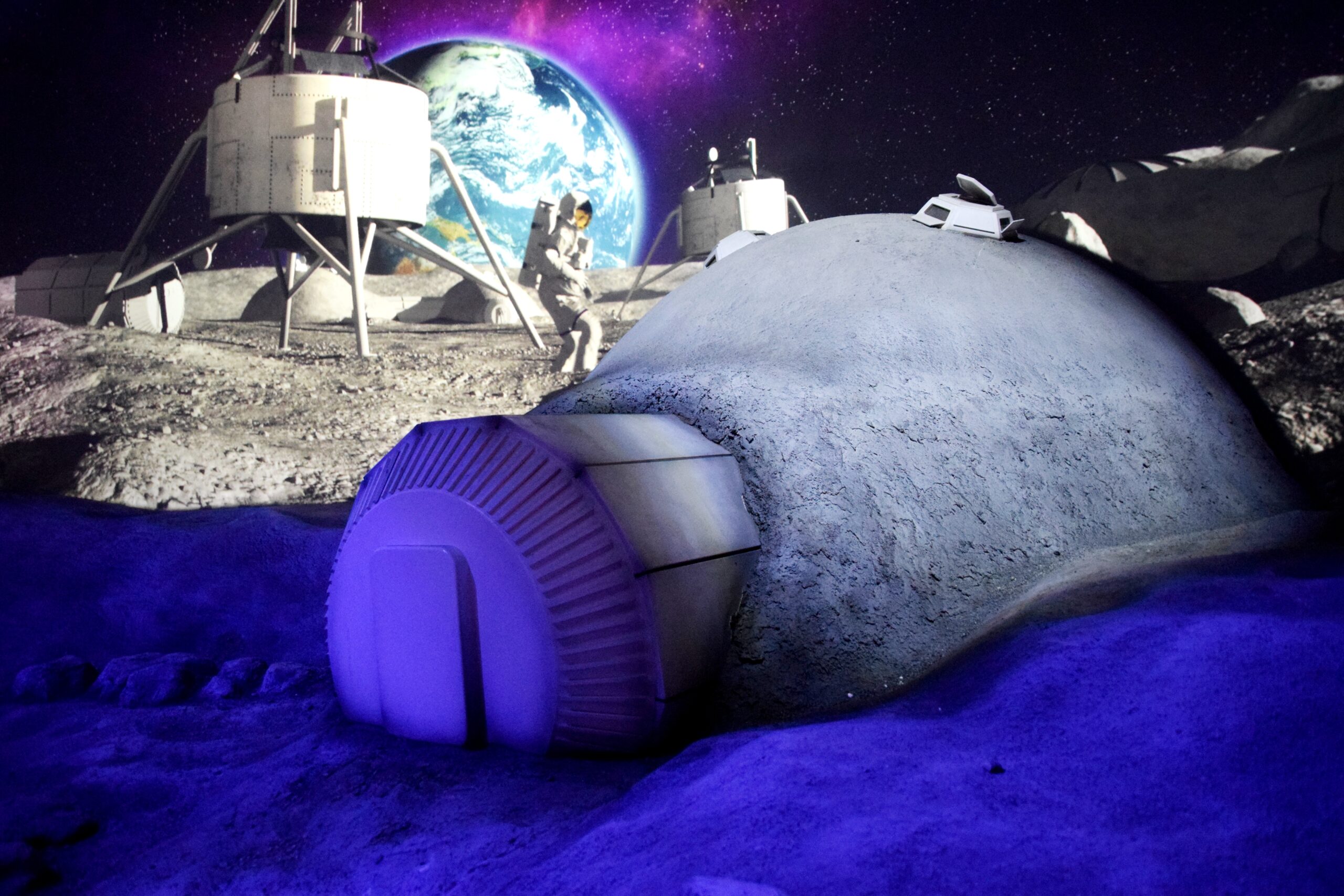

Space exhibit at the Museum of Future Energy, Astana; image: Ola Fiedorczuk

Space Garbage: The Environmental Toll

Baikonur is also increasingly at the center of growing environmental concerns. Reliant on UDMH proton fuel, launches from the site cause carcinogens, acid rain, and are conceivably responsible for the die-out of critically endangered species. In 1988 alone, over 500,000 saiga antelopes were found dead, though whether this was caused by pathogens from a biological weapons facility on Vozrozhdeniya Island or rocket fuel being jettisoned remains unclear. In October 2018, twenty-two tons of kerosene and liquid oxygen were dumped from an altitude of 50 kilometers following a booster malfunction; meanwhile, rats in the vicinity have developed chromosomal instabilities.

These contaminated materials are then sold on the black market, further spreading toxicity. Most of the metal eventually finds its way to China, where it is converted into aluminum foil, the kind of which is used to wrap sandwiches.

Attempting to circumvent Kazakhstan’s protest laws, over the decades campaigners against the base have taken to staging lone vigils, often with a cosmic bent. After Kazakhstan’s space chief dismissed demonstrators as “sick” in January 2013, an activist turned up at the site dressed as an alien in a mock attempt to kidnap the supremo and take him to Mars.

Whilst residents of the oblast have been hospitalized and farmers complain about the debris from rockets crushing their horses, over the years some have been glad to see the spaceport stay. Darting across the desert, for many years the regions scrap metal dealers built a thriving micro-industry upon scavenging fragments which fall from the sky.

Preparing the spacecraft Soyuz MS-06 for the launch to ISS with two American astronauts and one Russian cosmonaut; image: Ninara

The New Cold War in Space: Cooperation or Alienation

Previously, during the thawing of the Cold War, Baikonur served as a unique symbol for Russian-American partnership. The U.S. Space Shuttle program ended in 2011 leaving no American options for manned spacecraft to reach the International Space Station (ISS) at that time. This satellite boasts international ownership and operation that saw the West working with Russia to facilitate the transport of their astronauts. The service is very costly, however, with a ride for an American astronaut setting NASA back over $90 million.

Currently, the worsening geopolitical situation due to Russia’s war in Ukraine has strained relations to an all-time low. These tensions have recently endangered the fragile agreement that supports the ISS. Russian cosmonauts have used the station for propaganda purposes, and the Kremlin has even threatened to withdraw from the ISS entirely.

Baikonur has a rich and fascinating past filled with many firsts in space travel that should be in the Western curriculum and consciousness. It remains to be seen if those pioneering space achievements will also be part of our current collective quest for the stars.

The Soyuz MS-07 on the launch pad, Dec. 17, 2017; image: NASA.

This is part one of a three-part special on Baikonur. Join us soon for part two.