Rail, Water, and Helicopters – Uzbekistan’s “Limited Recognition” of the Taliban

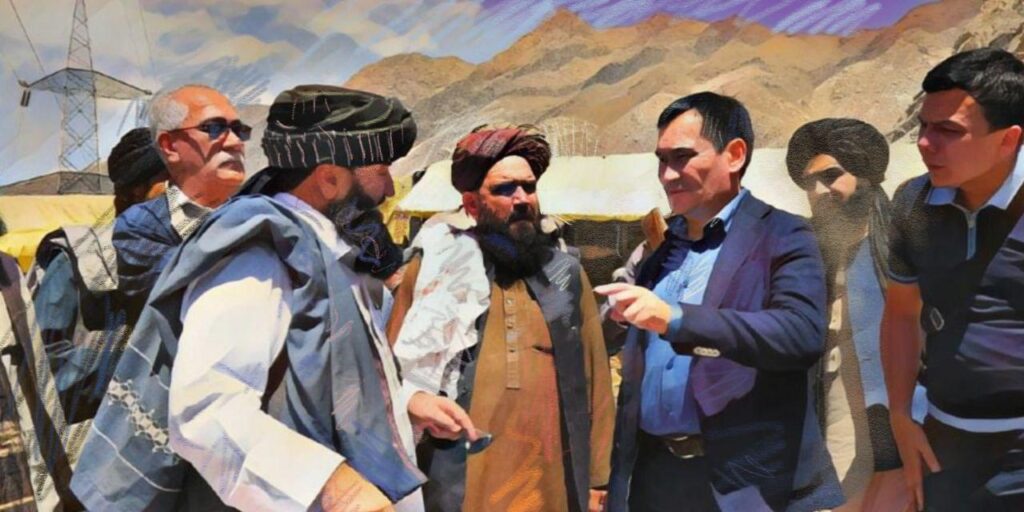

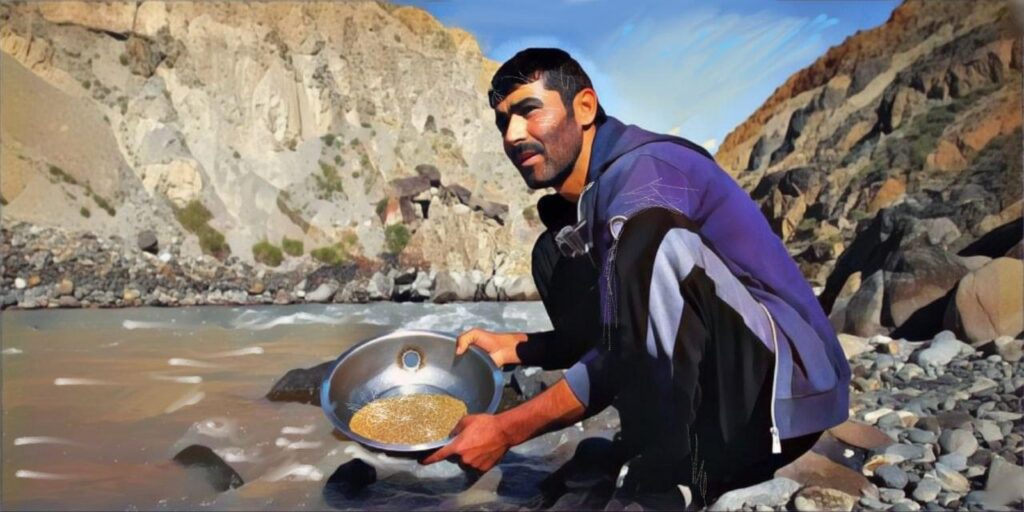

Uzbekistan has spent the middle of September embroiled in an increasingly tetchy press battle over an unusual topic: helicopters. The Taliban, who run the de facto government in Kabul, have long claimed that several dozen military aircraft and helicopters currently residing in Uzbekistan are rightfully theirs. On September 11, a Taliban official announced publicly that Uzbekistan had agreed to hand them back. This was reported widely in the regional media, with the Uzbek foreign ministry slow off the mark in denying these claims. The dispute goes back to the fall of Kabul in August 2021, when a total of 57 aircraft were flown from Afghanistan to Uzbekistan and Tajikistan as Ashraf Ghani’s government collapsed. “The helicopters came from the Afghan territory to Uzbek territory illegally, so actually we had the right to confiscate them,” Islomkhon Gafarov, an Afghanistan expert at the Center for Progressive Reform, a Tashkent think tank, told the Times of Central Asia. However, Gafarov adds that the aircraft were the property of the U.S. military loaned to the previous government of Afghanistan, and therefore, Washington will have a say in their return. This has not stopped the Taliban from continuing to demand the helicopters back for use in “humanitarian operations,” in the words of Foreign Minister Amir Khan Muttaqi. Such wrangling is part of the daily diplomatic in-tray for Tashkent when dealing with a neighbor whose government has not been recognized by almost the entire world. “Afghanistan is our neighbor,” said Gafarov. “According to the geopolitical situation, we have to conduct a dialogue with this government. It’s true, Uzbekistan hasn’t recognized the Taliban government, but de facto, we work with them; we’ve had diplomatic relations with them since 2018.” Tashkent certainly has reasons to work with the Taliban. Helicopters are a mere sideshow compared to two far larger issues that will define their relations for years to come: rail and water. Railway On the positive side of the ledger, the Taliban have brought to Afghanistan a reasonable degree of stability - enough to start contemplating large-scale infrastructure projects. In July, an agreement was struck between Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Uzbekistan to conduct a feasibility study for a trans-Afghanistan railway, with 647 kilometers of new track being laid to link Uzbekistan with Pakistan’s Indian Ocean ports. This railway could bring significant benefits to Uzbekistan, one of only two double-landlocked countries in the world. Currently, sea-bound exports must travel via Turkmenistan to Iran. Other routes almost all rely on going via Kazakhstan. The China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan railway, currently being constructed, should remove some of the need for sea-bound routes, but the Pakistan route would be faster. “The trans-Afghan route is the shortest way to the seaports of Karachi and Gwadar,” Gafarov told TCA. With a line from Termez, Uzbekistan, to Mazar-i-Sharif in Northern Afghanistan already operational, this only leaves two sections unbuilt - from Mazar to Kabul, and then from Kabul to Peshawar in Pakistan. The teams are still only at the feasibility stage right now, and have, with some chutzpah, predicted...