TASHKENT (TCA) — The prospects of Uzbekistan potentially joining the Russia-led Eurasian Economic Union entail both potential economic advantages and political risks for the country. We are republishing the following article on the issue, written by Fozil Mashrab:

During his address to the 20th Plenary Session of Uzbekistan’s Senate, on June 21, President Shavkat Mirziyoyev expressed fears that the country’s manufacturers could face increasing difficulties accessing their traditional export markets. His suggested solution, to join the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU—the Russian-dominated regional trade bloc), may have caught many by surprise, however (Kun.uz, June 21).

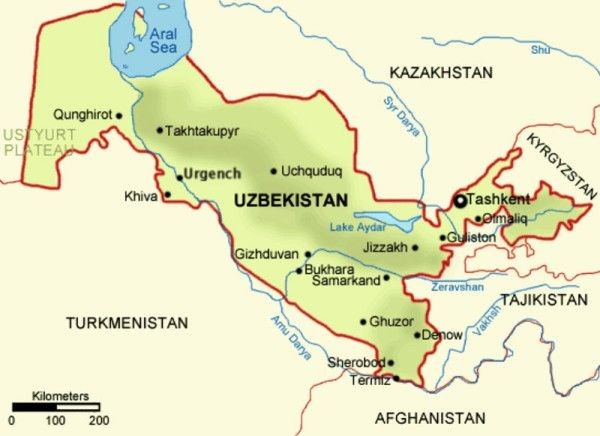

Mirziyoyev noted that, whether one likes it or not, Russia and the other EEU member countries—Kazakhstan, Belarus, Kyrgyzstan and Armenia—account for 70 percent of Uzbekistan’s external trade. He fretted that, soon after the Eurasian Union adopts common product marking standards, goods from Uzbekistan might face discrimination and additional restrictions. Mirziyoyev added that the government needs to thoroughly study the matter before making any final decisions but cautioned that joining the EEU without due preparations could itself lead to dire consequences (Kun.uz, June 21).

The fact that President Mirziyoyev did not rule out the possibility of Uzbekistan one day joining the Russian-led regional bloc constitutes an important departure from Tashkent’s previous policy of staying out of Moscow-dominated integrationist groups. His predecessor, the late president Islam Karimov, was deeply suspicious of Russia and consequently refused to join any regionalist organizations led by Moscow, all of which, he claimed, reminded him of the former Soviet Union (Ferghana News, January 13, 2015).

Until recently, senior officials in Mirziyoyev’s administration—particularly Foreign Minister Abdulaziz Kamilov—on several occasions stated that “Uzbekistan does not have plans to join the Eurasian Union, and such a step is not a foreign policy priority for the country.” Moreover, the former deputy minister of foreign trade, Shavkat Tulyaganov, said that “Eurasian Union membership would not be beneficial to Uzbekistan” (Eurasian-studies.org, February 12, 2018; Podrobno.uz, November 29, 2016).

However, Mirziyoyev’s comments before the Senate last month indicate that the costs of remaining outside of the EEU, which already incorporates two out of Uzbekistan’s five immediate neighbors, would only increase to the detriment of the domestic economy. This is despite the fact that, over the last three years, Uzbekistan removed many barriers to developing trade ties with key EEU member states (i.e., Russia, Kazakhstan and Belarus). In particular, cooperation with Russia has been expanding rapidly in new areas such as nuclear power plant construction, the purchase of military equipment and others (Gazeta.uz, June 28; UPL24, Nuz.uz, July 8; see EDM, July 10, 2018, October 22, 2018, July 22, 2019).

In April 2017, during President Mirziyoyev’s first visit to Moscow, he announced that Uzbekistan would be abolishing customs duties for many types of products manufactured in Russia. In turn, Russia granted so-called green corridors (simplified customs regimes) to Uzbekistan’s agricultural exports. Later, similar green corridors were extended to Uzbekistan’s textile exports to Russia (YouTube, April 5, 2017).

So far, Russia and other EEU countries have been willing to open their markets to Uzbekistani products only on the basis of reciprocity. As Russian President Vladimir Putin put it, “The trucks bringing Uzbek fruits and vegetables to Russia should be loaded with Russian goods on the way back” (YouTube, April 5, 2017).

These bilateral reciprocal arrangements have not always been easy to agree upon. Requests to establish a quota to export 200,000 tons of Russian sugar to the Uzbekistani market and to cancel excise taxes for imported Russian confectionary products placed Tashkent between a rock and a hard place, as these measures would have undermined local manufacturers. Moreover, sugar from other suppliers, such as Ukraine, Pakistan or Belarus, were offered at more competitive prices (Ferghana News, March 7, 2019).

In another case demonstrating the increasing difficulties with market access, Uzavtosanoat, Uzbekistan’s state-owned automobile manufacturer, whose sales in Russia completely stopped in the last two years, is planning to set up assembly plants in Kazakhstan, Russia and Kyrgyzstan. The aim is to gain access to the EEU market on more convenient terms. But whether such a step will make economic sense for Uzbekistan in the long run remains to be seen. After all, the country is in critical need of foreign direct investment itself; thus, it is questionable whether it is even in the position to make these kinds of costly investments abroad (Tengrinews.kz, July 4).

Despite growing ties with the Eurasian Economic Union, Uzbekistan faces increasing restrictions while it remains outside the bloc. As such, Tashkent’s current policy of avoiding EEU membership and relying solely on bilateral arrangements looks increasingly unreliable and disadvantageous—especially when one also factors in the current legal and financial difficulties faced by the 2.5 million Uzbekistani migrant laborers in Russia who sent home $4.2 billion in remittances in 2018 alone. Tens of thousands of these migrant workers choose to apply for Russian citizenship every year to ease their access to the Russian labor market (Cabar.asia, June 24).

And although the Uzbekistani authorities under President Mirziyoyev have recently given some indications that they may be considering joining the Eurasian Union, certain parallel developments suggest the opposite may actually be true. Instead, the government could actually be moving toward more protectionist policies following the brief period of liberalization and relaxation of foreign trade regulations that occurred after Mirziyoyev’s ascension to power. Specifically, under pressure from local manufacturers, the authorities are planning to introduce new regulations that will increase the average duties levied on all imported goods (including from EEU member countries) and reduce the number of goods exempt from duty collection. All of these measures, instead of bringing Uzbekistan closer to EEU standards, would widen the gaps and erect new barriers between them (Gazeta.uz, June 23, July 1).

Beyond trade, one must take into account potential political risks associated with membership in the Eurasian Economic Union, such as the frequently cited “risk of becoming hostage to Russia’s unpredictable and often dangerous foreign policy, with limited options of defending its own national interests” (Report.uz, June 26). Even if looked at purely through the prism of trade and economic calculations, however, Uzbekistani authorities will still face tough choices in the future while domestic manufacturers continue to clamor for restricted imports and greater protection from the government (Gazeta.uz, July 1).

This article was originally published by The Jamestown Foundation’s Eurasia Daily Monitor