Following the high-profile terrorist attack at Moscow’s Crocus City Hall in March and reports that eight Tajik immigrants were arrested in the U.S., the media spotlight has once again fallen on Islamic State Khorasan Province (ISKP), also known as “Wilayat Khorasan“, and the “Khorasan Project.”

Many observers link ISKP to the countries of Central Asia, even though the terrorist organization, as it has been designated for a long time, has purely Afghanistani roots. In addition, there is a lot of talk about its geopolitical ambitions for “recreating” the state of “Khorasan.” Where this region’s boundaries lie is the subject of debate. The most expansive definitions include northeastern Iran, western and northern Afghanistan, eastern Turkmenistan, and parts of Tajikistan and Uzbekistan. It is important to understand, however, that clear boundaries have never existed, and neither has a state with that name. In modern times, the term “Khorasan” has only historical and cultural connotations, with no political meaning attached to it.

ISKP has suffered a clear military defeat in the borderlands of Afghanistan and Pakistan, and faces significant opposition there. Still, weakening and even destroying the Taliban remains an important goal for the organization. It continues to fight in several regions of Afghamistan, which has prompted the Taliban to intensify their counter-terrorism efforts.

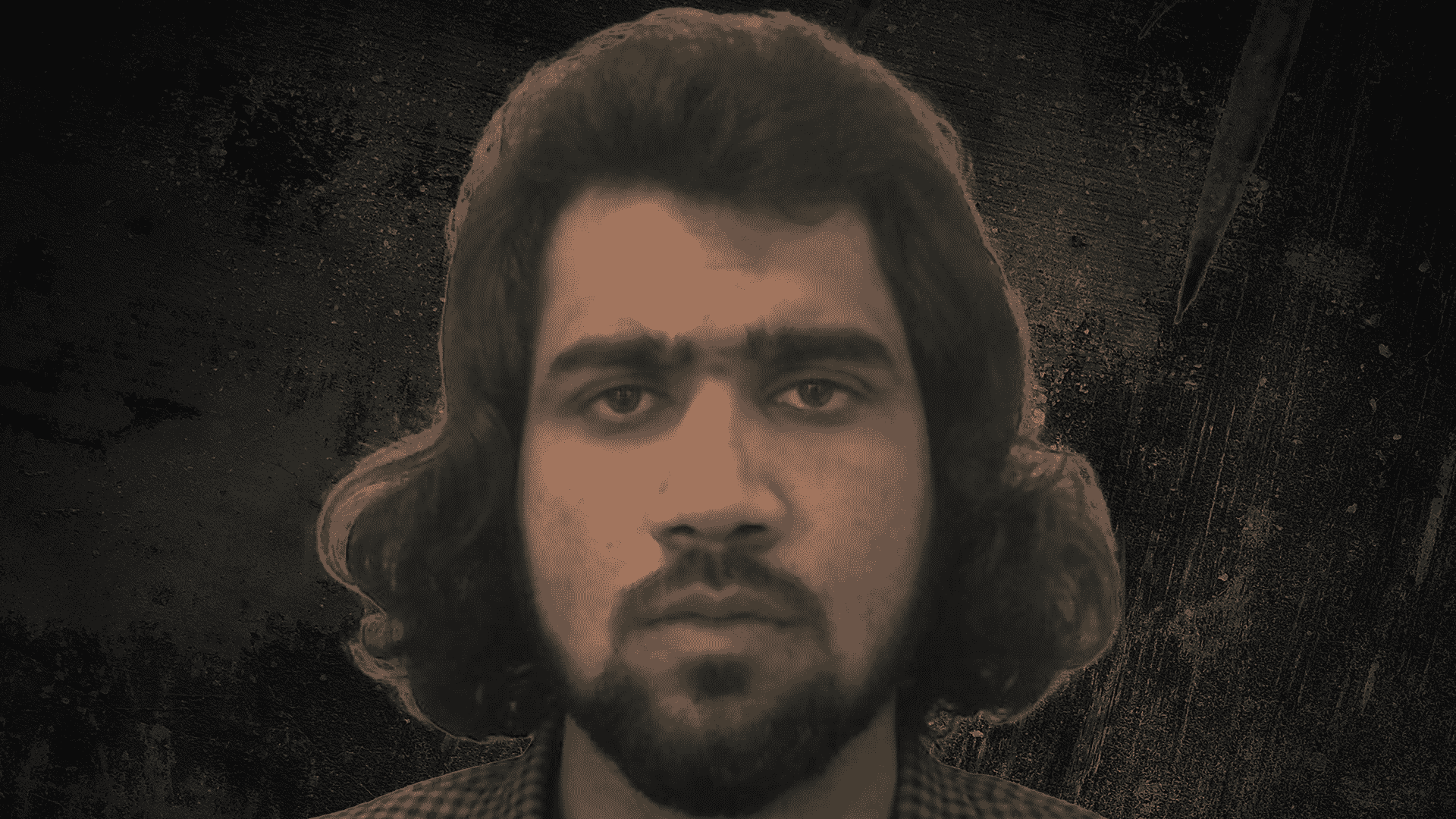

Sanaullah Ghafari, Emir of ISIS-K has a U$10 million bounty on his head; image: rewardsforjustice.net

The countries of Central Asia, having emerged out of the Soviet Union, are attractive for ISKP ideologists in the sense that they share a common historical and cultural past, while there are even linguistic similarities with Afghanistan (between the Persian languages).

The Russian internet portal and analytical agency, TAdviser, points out that ISKP, through its online propaganda publication, announced the start of a new campaign against the countries of the post-Soviet space in April 2022. In June of that year, the ISKP publication, written in the Uzbek language, declared that the countries of Central and South Asia would be united under the flag of the “Islamic Caliphate.”

TAdviser highlights that Turkmenistan has a special place in ISKP propaganda because according to the group a large part of what is now Turkmenistan was previously part of “Greater Khorasan,” while the foreign policy of the Turkmen authorities of actively cooperating with the Taliban is wholly at odds with the core goals of ISKP. The Lapis Lazuli corridor linking Afghanistan to Turkey, along with the Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India gas pipeline (TAPI) which is being developed, are identified as priority targets for ISKP.

But what in fact is ISKP? As previously noted by The Times of Central Asia, the answer to this question is known by only a very narrow circle. Indeed, no one can provide objective data on the qualitative and quantitative composition of ISKP. Nevertheless, the group is taking on real dimensions in the media.

The threat to Central Asia from ISKP looks more virtual than real at this point. Any small group of terrorists can declare themselves part of ISKP, and, without any proof, the press will often accept this as truth, with ISKP presented as a “formidable regional entity.” However, in the Central Asian republics, there are not and will not be the relatively comfortable conditions that the ISKP has in Afghanistan.

The countries of Central Asia have developed both individual and collective experience in combating radical groups. In addition, significant measures are being taken within the framework of the Regional Anti-Terrorist Structure of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) and the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO).

Of course, there is a basis in Central Asia upon which religious-ethnic radicalism can be cultivated, such as low living standards and a shortage of social justice. Other factors, such as territorial claims, ethnic divisions, issues around water usage, and the risk of so-called “color revolutions,” have also not gone anywhere.

A cow grazes by the shell of a burnt-out bus in the Pyanj River separating Tajikistan and Afghanistan; image: TCA, Stephen M. Bland

It stands to reason that ISKP ideologists will focus on these vulnerabilities. Currently, Tajikistan looks to have been chosen as the main pressure point – the information space in recent months has been replete with reports about the involvement of Tajiks in the activities of the Islamic State. This is understandable given the difficult economic situation in the country, high labor migration, the lasting effects of the civil war, and strict state control over the religious sphere. Among the five Central Asian republics, Tajikistan, with its Persian language and cultural differences from its Turkic neighbors, appears rather isolated. In addition, about 5% of Tajikistan’s population is Ismaili Shia; this “feature” does not and cannot play any role whatsoever in modern interstate relations in the region, but, according to some experts, it may be cultivated by Islamic State ideologists.

In any case, the situation with movements such as ISKP requires the countries of Central Asia to have shared views and common approaches in countering the politicization of Islam and its use as a tool in geopolitical games.