At the Tashkent City Mall, a new Greek restaurant promises what it calls an “unforgettable adventure” for foodies. Superhero fans can check out the Deadpool & Wolverine movie at the mall’s cinema. But it’s not all fine dining and pop culture – a multimedia exhibition there traces the saga of students from Central Asia who studied in Germany and fell victim to Stalinist purges in the 1930s.

Why was the exhibition, featuring visual and sound installations, installed in a glitzy shopping complex where lots of people, especially young people, relax and mingle?

A clue lies in the Uzbek government’s enthusiasm for highlighting the history of the “Jadids,” members of a progressive movement of pious Muslims who pursued secular education, openness to the outside world and early ideas about independence, even as they faced restrictions and oppression under Russian colonial and then Soviet rule. A century later, the Jadids are a model for Uzbekistan, which seeks new international partners as it searches for ways to train and harness its growing population of young people.

The three-month exhibition, titled “Jadids. Letters to Turkestan,” was supported by the state Uzbekistan Art and Culture Development Foundation. It opened on July 18 and coincides with upcoming days of national commemoration on Aug. 31 and Sept. 1. One prominent visitor was Saida Mirziyoyeva, daughter of Uzbek President Shavkat Mirziyoyev and one of his senior aides.

Mirziyoyeva said on the X platform that she was impressed by the exhibition’s account of about 70 Jadid (“new” in Arabic) students, “who made significant contributions to our people’s science and culture during their short lives.”

The students came from Turkestan, an old name for Central Asia. They included Uzbeks as well as Kazakhs, Kyrgyz, Turkmen and Tatars. In 1922, as the Soviet Union was taking shape, they traveled to Germany and studied agriculture, textiles, chemistry, electrical engineering, mining, philosophy, teaching and medicine.

“At the root of all this was the dream and goal of achieving national development and national independence,” scholar Naim Karimov wrote.

The Stalinist regime saw the students’ education abroad and exposure to different ideologies as a threat to Soviet control. Most of the students who returned to Uzbekistan were falsely accused of espionage and executed or exiled. There was a particularly brutal period of repression in October 1938.

The exhibition focuses on the letters, many hopeful and idealistic, that the students wrote while they were in Germany. One haunting section is dedicated to the persecution that they suffered when they returned home. There is a display of the names of Jadids who were shot in 1937-1938 – some had gone to Germany and others helped them travel there.

An audio segment plays excerpts from the interrogation of a sponsor of the Jadids, who is accused of treason and says: “I want to live, don’t kill me!”

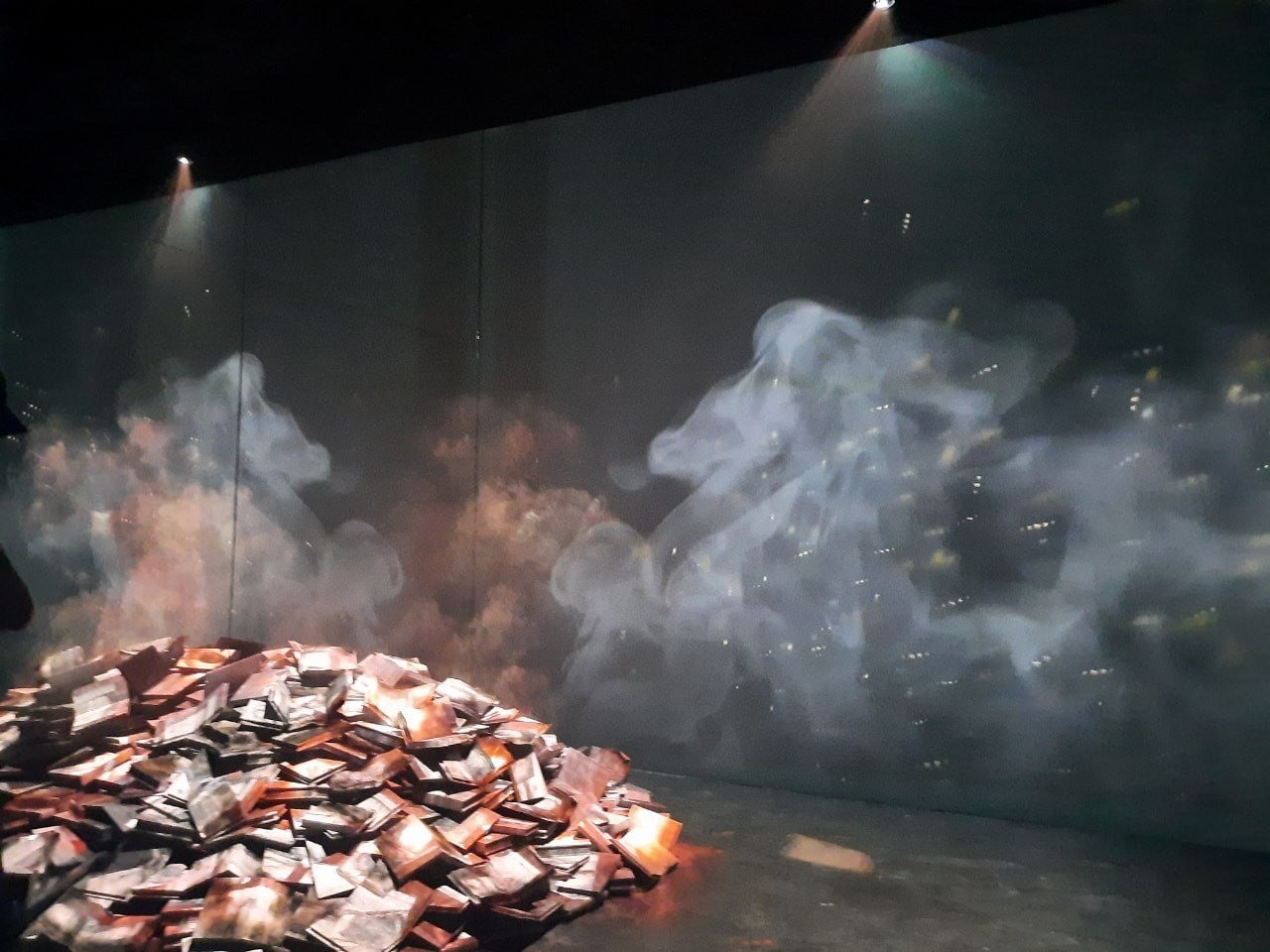

One installation depicts a pile of books that were seized by Soviet authorities and set on fire. A father’s appeal can be heard: “Don’t burn my daughter’s books! Her only fault is that she studied in Germany.”

——-

One of the students whose story is told in the exhibition at Uzbekistan’s biggest mall is Khairiniso Majidkhanova, who studied in Germany for five years and worked as a doctor on her return to Uzbekistan.

“I was lucky enough to send the first Uzbek girl to a distant country for knowledge!” Majidkhanova’s father wrote in a letter.

Kholida Kadirova, Majidkhanova’s niece, said in a documentary shown on Uzbek television several years ago that Majidkhonova was imprisoned on September 15, 1937. Soldiers searched her room, confiscated books, newspapers, magazines and letters, and burned them in the yard.

Majidkhonova, 32, was shot and killed on Oct. 9, 1938.

“Unfortunately, my aunt had big dreams,” said Kadirova, tears in her eyes. “She started translating various medical manuals brought from Germany from German into Uzbek, and started working on scientific research. She encouraged me to study in this field in the future, she made me enjoy the light of enlightenment.”

——-

Another student was Sattar Jabbar, known as the first Uzbek chemist. Under the pseudonym Ertoy, he wrote about German hospitality:

“When we first arrived in Germany, many reporters were excited to meet us. Any German opened his doors to welcome us into his family. From ordinary teachers to doctors and professors, they spared no effort to help us learn the language. As Germans love the world, they are also very interested in Turkestan. They know our country, our history, our prospects better than Turkestan people.”

Jabbar returned to Uzbekistan in 1931 and gave lectures on chemistry at the Central Asian State Medical Institute (now the Tashkent Medical Academy). In 1936, Jabbar received the title of professor. In 1937, he was arrested and accused of anti-Soviet activities. He denied the accusations but was executed.

——-

Saida Sherahmedova was among students who learned about the repression back home decided to stay in Germany or other countries. Her brother Nasriddin and nephew Fuzail had gone with her to Germany and went home to work – Nasriddin as an economist and Fuzail as a water management specialist, helping to construct the Great Ferghana Canal project in the 1930s. But they were rounded up and killed in the purges at the end of that decade.

So, Sherahmedova moved to Turkey after finishing her studies. She taught at a girls’ lyceum in Istanbul and died at age 87 in 1992, one year after Uzbekistan gained independence when the Soviet Union collapsed.

——–

Each Aug. 31, at a Tashkent memorial site called Shahidlar Xotirasi (Memorial to the Victims of Repression), the government leads a ceremony for the thousands of Uzbek people who were killed during repressive periods under Russian colonial and Soviet rule. Uzbekistan celebrates its Independence Day on Sept. 1.