Indian author Arundhati Roy once said, “Either way, change will come. It could be bloody, or it could be beautiful. It depends on us.” Almost three years after Taliban’s resurgence to power in Afghanistan, there are practically no developments to highlight in its relations with the outside world. The situation remains at a dead end as the international community and the authorities in Kabul are stuck on intransigent issues, and as Afghanistan continues to face a humanitarian crisis.

In the context of current geopolitical realities after the recent fall of its “democratic” regime, Afghanistan finds itself in a gap between the experiences of the past and a yet undetermined future. It has a unique opportunity to transcend its reputation as the “graveyard of empires” and determine its own fate while simultaneously integrating into the international community. How the de facto authorities in Afghanistan handle this opportunity will not only shape the future of the Afghan people and the region, but also influence the development of the entire global security paradigm.

Currently, the Taliban have every opportunity to lay the foundation for a new model of regional and international security, which would allow them to create conditions for the return of Afghanistan to the system of normal international relations. But they need to act quickly. Rising tensions in the Middle East engage almost every global and regional power, and further escalation there will negatively affect the situation around Afghanistan. In this unpredictable geopolitical environment, the Taliban can either take the lead on new security arrangements or once again experience an undesirable worsening of the security situation that goes beyond their control.

A path forward is possible with the Taliban acting responsibly at the helm

It seems that since the Anglo-Afghan wars of the 19th century, the world has become accustomed to seeing Afghanistan as a place where global geopolitical steam can be let off. But the Afghan people deserve progress, and various outside actors have offered different proposals. What the Taliban need is a chance at a breakthrough where they are the key player and can take full responsibility. The international community needs to allow such an opportunity to serve as a “maturity test” with which it can gauge the Taliban.

At this important juncture, the international community must support Afghanistan in determining its own future. If external actors continue to promote political blueprints, Afghanistan will once again become a site for proxy wars, an arena of rivalry and a fertile ground for old narratives about international terrorism and other threats. Slamming the Taliban for their democratic failings, on which they clearly do not share the outsiders’ perspectives, will not yield productive results.

For its part, if Kabul is really seeking to be a key player in Asia and a regular participant in international affairs, and if it seeks to realize its significant geographic and economic potential, then it must start implementing practical initiatives involving regional countries and international organizations in a dialogue on security.

Maintaining internal security and stability remains the main problem of modern Afghanistan. While other issues, including women’s rights and inclusive governance, are also highly relevant, they are not the regime’s current priority. This is due to a simple fact of life: Without security, there can be no development. That should be the slogan on which Afghanistan’s authorities work to build relations with the world.

Today, economic interests of regional countries (India, Iran, China, the UAE, Pakistan, Russia, Turkey, and the Central Asian republics) pose major geopolitical challenges for Afghanistan, which in turn presents potential opportunities for these countries. Indeed, these nations have shown an ability to look past the Taliban’s democratic failings and get to the root of the problem ailing the country.

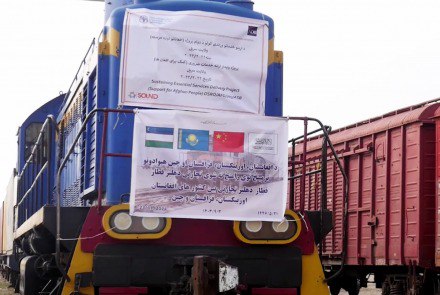

Security is the basic condition for stable economic growth. Trade relations alone are not enough, even though the Taliban have been relatively successful at building them. Investors will hesitate entering Afghanistan until the authorities can provide a reasonable and predictable level of security. Take, for instance, the Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India (TAPI) gas pipeline nor the Trans-Afghan railway; neither will materialize without a environment of security.

As far as domestic actors go, the Taliban are singularly capable of ending terrorism in Afghanistan once and for all. No other military-political group or organization that is in opposition to the Taliban has coped or can cope as well on this front. The Taliban share the same early history as the “Afghan Islamic State” and other small terrorist groups in that they understand the issue of terrorism better than others.

Identifying tangible steps needed to ensure security and stability

Kabul needs to initiate a new platform of discourse on Afghanistan’s internal security issues with the participation of the country’s neighbors.

The Taliban leadership, as well as the international community, must understand that the decisive role in the new security model should be played by Iran and Pakistan, who have acted as antagonists in Afghanistan’s modern history by using the country as a background for their proxy wars with third parties (the USSR, the U.S. and its allies, and parties to civil wars).

Iran and Pakistan are historically most in tune with Afghanistan in terms of understanding ethnic, economic and political conflicts and border issues. In addition, the three countries will be involved in developing international transport and energy infrastructures with the participation of a range of other states. Moreover, Iran and Pakistan, like Afghanistan, have long been directly or indirectly connected in international discourse to the spread of international terrorism.

The need to combat terrorist activity on Afghanistan’s borders with Pakistan and Iran – a very acute and persistent problem – is such that separate intergovernmental formats among Kabul, Islamabad, and Tehran are needed. This “troika” represents the most critical actors to provide guarantees of Afghanistan’s security at the international level.

The essence of the new the initiative is forming a permanent trilateral contact group on security matters (particularly on counter-terrorism) among Afghanistan, Iran and Pakistan. This format will fundamentally differ from existing multilateral fora, which in practice do not have the ability to deal with Afghanistan’s security problems. The creation of such a contact group should be initiated by the Taliban as the guarantor of border security for Pakistan, Iran, India, China and the Central Asian republics.

In this context, it is worth mentioning the Islamic Military Counter-terrorism Coalition (IMCTC), which includes Pakistan but not Iran. The creation of a permanent contact group would be the missing regional link for the IMCTC and would help bring the attention of the rest of the Islamic world to Afghanistan’s problems in the context of counter-terrorism. Through the IMCTC, Afghanistan could become a point of cooperation between Sunnis and Shiites, which is also important for the Taliban given Afghanistan’s own Shiite population.

In the future, if this troika manages to achieve even a minimum level of understanding and to establish practical cooperation, the format could be further strengthened by the involvement other actors, primarily from Central Asia.

The need for a mediator

Given the rather difficult and sometimes contentious relations between the above three countries, another country or an international organization could be called on as a mediator to provide extensive assistance in the form of political consultations, a high level of diplomatic involvement and provision of instruments for implementation. Once again, it should be up to Kabul to decide on an acceptable intermediary.

The complexity of the first steps in creating such a security structure will necessitate a mediator. In particular, public and private consultations will be required. In addition, the opposition from both the previous governments and “northern” anti-Taliban groups, as well as representatives of big business in Afghanistan, will need to be brought into these consultations, either in parallel with one other or separately.

These consultations should primarily focus on building relationships and trust and exploring options that could meet the needs of all parties. In this context, the Taliban could also opt for track II diplomacy and draw on the capabilities of a large expert community in this area. Afghan and foreign think tanks, experts, media and bloggers, along with social networks and public circles, can lay the foundation for advancing a decided set goals.

Possible positive outcomes of a successful security strategy for Afghanistan and beyond

The immediate first success for the Taliban in this endeavor would be establishing an interaction with regional partners and demonstrating to the outside world a responsible attitude toward common issues plaguing the region.

Regardless of the circumstances, the initial steps taken by Iran, Pakistan and Afghanistan would provide a body of knowledge for the international community, allowing for a deeper understanding of the realities for further developing relations between Afghanistan and international actors. This is a unique opportunity for Kabul to show to the international community that it can hold a constructive position and has a real desire to build important and effective state mechanisms when needed.

The long-term impact would be establishing links between Afghanistan and the international community toward resolving Afghanistan’s other pressing problems. After all, with immediate security considerations addressed and trust established, Afghanistan and its partners will be able to focus on cooperating on further development.

Aidar Borangaziev is a Kazakhstani diplomat. He has experience of diplomatic service in Iran and Afghanistan. Founder of the Open World Center for Analysis and Forecasting Foundation (Astana). He is an expert in regional security research.