Completely covered by a huge textile patchwork piece, softly moved by the wind, the façade of the Mathaf Museum in Doha promises visitors something fascinating and alluring. Coming closer, attendees could read a series of statements in various languages on the fabric.

The effect of familiarity and estrangement at once was the purpose of Azerbaijani artist Babi Badalov, who realized the piece. By layering phrases in Arabic, Cyrillic, and Latin with calligraffiti and employing disjointed grammar and syntax, the artist meant to visually disrupt “linguistic imperialism” and show how Europe’s modern civilization owes much to Arab civilization.

The Mathaf Museum in Doha; image: TCA, Naima Morelli

This specially commissioned work, called Text Still (2024), is nothing but an appetizer for the show Seeing is Believing: The Art and Influence of Gérôme. Organized by the forthcoming Lusail Museum — an institution under development in northern Doha that will house the largest collection of the so-called Orientalist art — the exhibition features loans from institutions such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the Islamic Arts Museum in Malaysia.

The main part of the show is dedicated to French artist Jean-Léon Gérôme, who lived and worked in the 19th century and was profoundly influential in his depictions of the Middle East, North Africa, and South Asia. His works shaped Western perceptions of these regions during an era when colonialism and “Oriental Studies” were cementing global power dynamics.

The show included a historical and biographical exploration of Gérôme’s life, timed to celebrate the 200th anniversary of his birth, as well as a photographic section curated by Giles Hudson dedicated to visions of the Orient from Gérôme’s time to today.

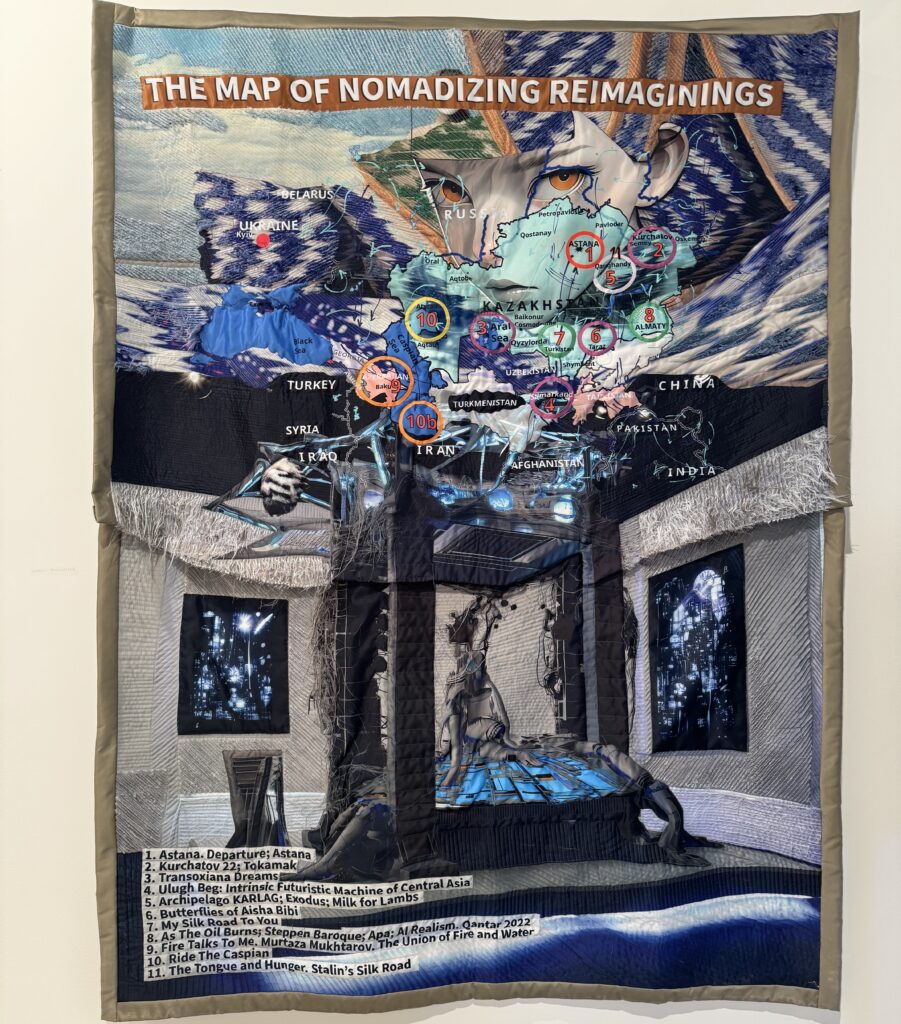

But it is in the third section, centered on contemporary art and called “I Swear I saw That”, that Central Asian artist really enter into a close dialogue with Gérôme’s Orientalism, turning it on its head.

Sara Raza, curator of this section, takes Badalov’s textile work as a case in point: “Badalov inverts Edward Said’s mission of examining Western perceptions of the Orient, focusing instead on Eastern perceptions of the Occident, and vice versa,” she told The Times of Central Asia.

Edward Said’s concept of Orientalism, as detailed in his groundbreaking 1978 work of the same name, is an institutionalized program of Western knowledge, based mostly on projections, mystification, and imagination – and includes works of art as well as the academy – which is directed to justify a supposed Western superiority and imperialism over Eastern populations.

“I Swear I Saw That” interrogates Jean-Leon Gerome’s way of seeing, which Sara Raza recognizes as a “fantastical and highly mythologized vision of the East,” and looks at how artists from both the Middle East, the Arab world and Central Asia fought back.

A Central Asia and Caucasus expert who works extensively in the Middle East, Raza has examined the process of the exoticization of Eastern populations for a long time. She coined the term “Punk Orientalism,” which also became the name of her book and curatorial studio. She takes the reflections of Edward Said as a starting point, and looks at how the Central Asian population has been seen through a stereotyped lens by both Europe and the Soviet Union. Raza brings a punk, DIY approach to her curatorial method, which reflects the same attitude of many Central Asians who have a rebellious spirit and create art with a grassroots, bottom-down approach.

Installation by Erbossyn Meldibekov; image: TCA, Naima Morelli

From the stylized figures of Moroccan artist Baya – a trailblazer in the last century who was close to the surrealists – to contemporary artists like the Kazakh Erbossyn Meldibekov, the selection doesn’t only span Eastern geographies, but also different generations.

The installation by Meldivekov, featuring a horse’s lower legs frozen in motion and placed on a white podium, is particularly haunting. The work was conceived as a commentary on the rise and fall of historical figures celebrated by statues across Central Asia. The felling of these statues started following the collapse of the USSR as part of a state-sponsored nationalist agenda and was part of a plan to revive the region’s epic past, a topic dear to Meldibekov.

While his installation is dedicated to 15th-century Italian Captain Erasmo Gattamelata, and his statue to Italian Renaissance painter Donatello, Meldibekov also references Gérôme’s bronze statue of the 14th-century Uzbek emperor, Timur.

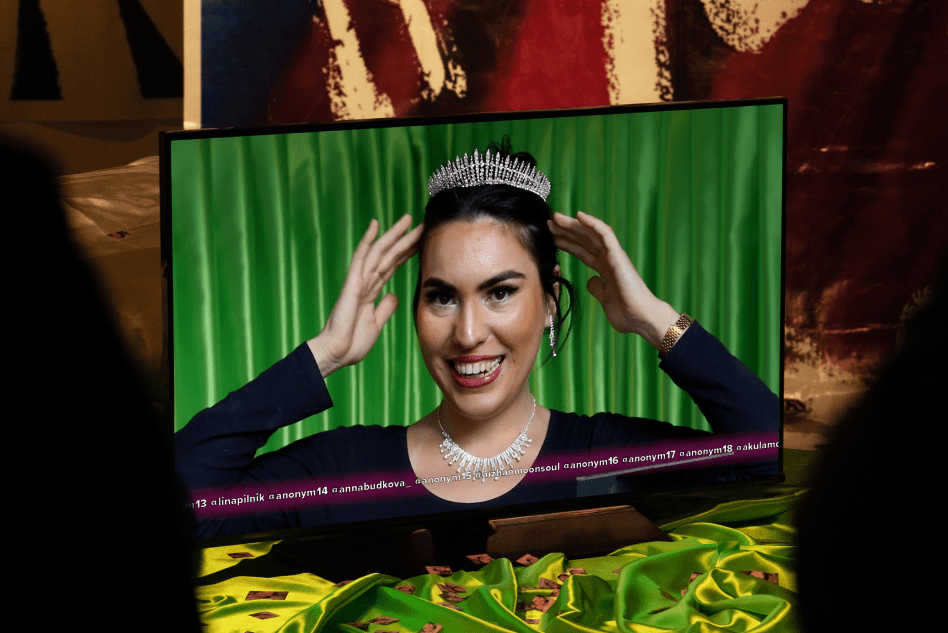

But the work which is probably more impactful in moving forward the discussion on Orientalism is a series of photographs titled “Girls of Kyrgyzstan,” which have distinctive GenY/ GenZ aesthetics.

Created by Uzbekistan-born Kyrgyzstan-bred artist Aziza Shadenova, a multidisciplinary artist and musician of Kazakh ethnicity, it encapsulates the ethos of the generation born right after the collapse of the USSR in 1991, who grew up familiar with the internet from an early age.

The series speaks of the pervasiveness of images on the internet as a means to represent the self, freeing themselves from both Western and the Soviet narratives, as well as debunking previous social norms and myths around the representation of Central Asian women.

Aziza Shadenova, “Girls of Kyrgyzstan”; image: TCA, Naima Morelli

In the catalogue essay, Sara Raza explains that social media is a space where Kyrgyz girls can reclaim their sense of autonomy, posting images and texts that involve encoding hidden messages in clothing, hairstyles, gestures, and postures that are generationally-specific.

Overall, what emerges from the third chapter of “Seeing is Believing: The Art and Influence of Gérôme,” is a clear vision of how artists are entering a new era of de-orientalization. What Sara Raza and the artists suggest in the show is that in order to move forward the discourse on Orientalism, artists from all geographies must be aware of stereotyping and correct historical inaccuracies.

“Collectively the artists in ‘I Swear I Saw That’ embody conceptual positions that challenge obsolescent Eurocentric historical precedents and can tackle issues of prejudice, power and knowledge by way of conscious visioning,” says Sara Raza. “Witnessing becomes holy writ: mysterious, complicated, powerful. Necessary.”

And if the Gulf countries are providing the ideal framework, in terms of institutions, to be a place for these voices and narratives, Central Asian artists are at the forefront of this vision.