Stealing Brides, Ignoring Justice: The Battle Against Forced Marriage in Central Asia

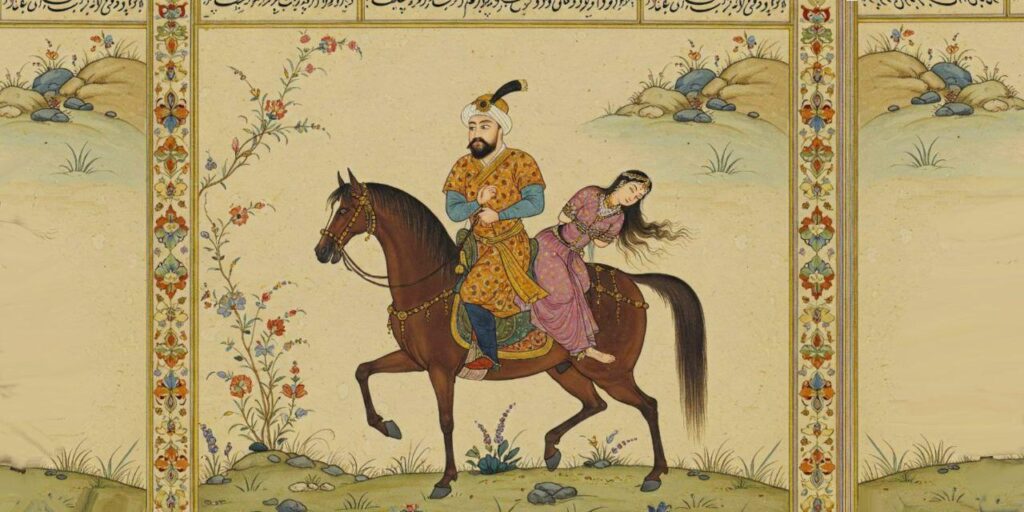

The abduction of girls for forced marriage remains a troubling and persistent practice across Central Asia. While Kazakhstan has been progressively tightening its legal framework to better protect women's rights, bride kidnapping continues to pose a serious human rights challenge throughout the region. Fighting the Middle Ages? Bride kidnapping has long been practiced in Central Asia and the Caucasus. In contemporary times, some instances are consensual, carried out as a form of cultural theatre to reduce the high cost of weddings in traditional societies. However, when carried out without the woman’s explicit permission, the ritual becomes a form of gender-based violence. Efforts to combat non-consensual bride kidnapping have been ongoing since the Soviet era, yet the practice endures. According to some Kazakhstani legislators, the current laws are no longer adequate to address the full scope of the issue. The existing criminal code’s general provisions on abduction, they argue, fall short of tackling the specific dynamics of forced marriage. Mazhilis Deputy Murat Abenov has proposed introducing explicit criminal liability for coercion into marriage. “Over the past three years, 214 complaints have been filed in Kazakhstan from people who were forced into marriage. Only ten of them reached court. Hundreds of criminal cases were simply closed,” Abenov stated. “Even though the girl proved that she had been kidnapped, that she had jumped out of the car, that force had been used against her, nothing could be done.” New legislative amendments have been drafted and are expected to be debated in the Mazhilis, Kazakhstan’s lower house of parliament. The proposed law introduces a scale of penalties based on the severity of the offense. “There is administrative liability, there will be a large fine, and in serious cases where the girl is under 18 or where force is used or by a group of people, there will be more serious liability, up to criminal liability, five to seven years in prison,” Abenov explained. This new law could be enacted by the end of 2025. Kazakhstan's Human Rights Commissioner, Artur Lastaev, addressed the issue in February 2024 in the wake of a high-profile case in Shymkent. “The practice of kidnapping girls for the purpose of marriage is still widespread in our country, especially in the southern regions. In some cases, such actions result in sexual assault, humiliation, unlawful deprivation of liberty, and even suicide,” Lastaev stated. “Saltanat’s Law” Written in Blood In June 2024, Kazakhstan implemented a sweeping new law entitled “On Amendments to Ensure the Rights of Women and the Safety of Children.” Though years in the making, the law is colloquially known as “Saltanat’s Law,” named after Saltanat Nukenova, a young woman who was brutally murdered by her common-law husband, Kuandyk Bishimbayev, a former senior government official. In November 2023, Bishimbayev beat Nukenova over the course of a night in a restaurant in Astana. After she lost consciousness, he attempted to conceal the crime instead of seeking medical help. In May 2024, following a highly publicized trial, Bishimbayev was sentenced to 24 years...