By Bruce Pannier

Incidents in May showed two Central Asian countries – Kyrgyzstan and Turkmenistan – are afflicted by racism that is tacitly or explicitly supported by their governments.

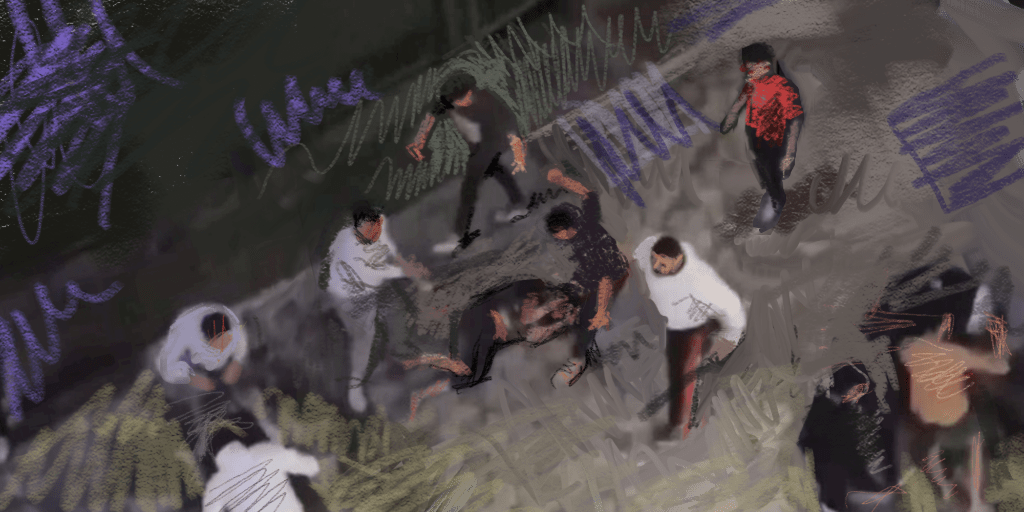

Overnight on May 17-18, hundreds of young Kyrgyz men gathered in eastern Bishkek near a dormitory used by foreign students. The Kyrgyz men were angered by a video posted on popular Kyrgyz social media sites on the morning of May 17 that showed a fight in Bishkek on May 13 between a small group of Kyrgyz and foreigners.

The foreigners in the fight on May 13 turned out to all be Egyptians, and they were all detained. However, some social media posts claimed at least some of the foreigners involved in the fight were Pakistanis.

Many people from Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan come to Kyrgyzstan to study at universities, particularly at medical colleges. More than 90% of foreign students at Kyrgyz universities are from India and Pakistan.

A smaller number, in the low thousands, are working there illegally.

In March, Kyrgyz authorities launched a campaign to find and deport illegal migrant laborers some 1,500 Pakistanis and 1,000 Bangladeshis have been caught.

There have been isolated incidents when Kyrgyz were involved in physical altercations with South Asians in recent years, but nothing on scale of what happened in May 17-18.

Besides bursting into the dormitory and assaulting foreign students, a group of some 60-70 Kyrgyz men broke into a sewing factory in Bishkek early morning May 18 and attacked foreign workers, who mostly from Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan.

At least 41 people were injured, most of them South Asians.

Pakistan in particular reacted, summoning the Kyrgyz Charge d’Affaires in Islamabad while a group of Pakistanis protested outside the Kyrgyz Embassy. Pakistani authorities also sent charter flights to Kyrgyzstan that brought back more than 1,000 Pakistani citizens.

Kyrgyz authorities criticized the police for failing to calm the situation before it went out of control and later 10 policemen were sacked. Deputy Cabinet Chairman Edil Baisalov went to the dormitory to meet with some of the foreign students and apologize for the harm done to them “by a bunch of hooligans.”

The top two people in the government – President Sadyr Japarov and head of security service Kamchybek Tashiyev – were more equivocal in their comments on the violence.

Since coming to power in late 2020, Japarov and his longtime friend Tashiyev have promoted nationalist policies. Their emphasis on respecting Kyrgyz traditions and customs has gained them significant popularity in Kyrgyzstan.

They need such support in a country that has had three revolutions since 2005, including the October 2020 revolution that resulted in them occupying their current positions.

Young Kyrgyz men, like the hundreds who gathered on the evening of May 17, are an important pillar of support for Japarov and Tashiyev.

President Japarov vaguely blamed “forces interested in aggravating the situation,” and added, “The demands of our patriotic youth to stop the illegal migration of foreign citizens and take tough measures against those who allow such activities are certainly correct.”

Tashiyev remarked the “main demands” of the hundreds of Kyrgyz men who were on the streets on May 17-18 “concerned an increase in the number of foreigners working in our country, an increase in the number of students and workers from Bangladesh, Pakistan, India, Egypt and other countries.”

Tashiyev said, “I believe that the demands of the guys who gathered yesterday are, to some extent, correct.”

In Turkmenistan discrimination is clearly part of state policy.

“Uch arka,” the practice of checking an individual’s background going back three generations has been enforced since 2000.

This genealogical requirement certifies that individuals’ previous three generations of relatives (parents, grandparents, and great-grandparents) who have not committed any serious crimes. The policy also helps separate ethnic Turkmen from other people living in Turkmenistan.

It is nearly impossible to find a position in a government organization for people who are not ethnic Turkmen.

School children are required to submit uch arka forms when they enroll.

In May 2024, at the graduation ceremony for students in the western city of Balkanabad, school authorities segregated non-Turkmen students out of the group that accepted diplomas in front of the city’s central library.

When the president visits towns and cities, the schoolchildren paraded out to meet him are usually chosen because they meet the uch arka requirements.

It is not only schools.

Balkanabad is the provincial capital of the Balkan Province. Earlier in May, all employees of the Balkan provincial medical facilities had their uch arka credentials checked.

This appears to have also targeted ethnic Turkmen whose recent ancestors may have committed some crime. That would be sufficient grounds for dismissal, but it also ensures ethnic Turkmen occupy the top spots in the medical field.

Kyrgyzstan had long been considered the most democratic of the five Central Asian countries, though that is changing under President Japarov, and Turkmenistan the most repressive. Their brands of ethno-nationalism are a dangerous sign for countries with increasingly authoritarian governments and decreasing possibilities for employment or improvement in the socioeconomic situation of their people.

Bruce Pannier is a Central Asia Fellow in the Eurasia Program at the Foreign Policy Research Institute, the advisory board at the Caspian Policy Center, and a longtime journalist and correspondent covering Central Asia. He currently appears regularly on the Majlis podcast for RFE/RL.