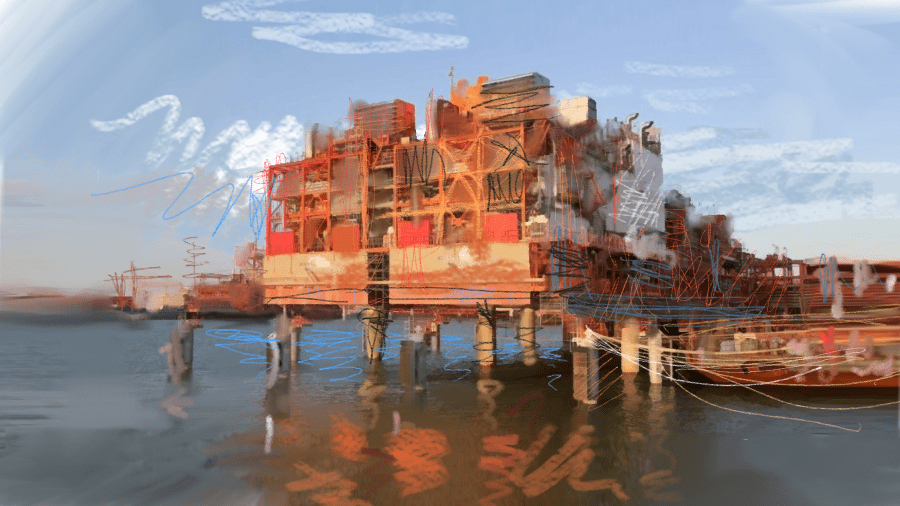

Kazakhstan is demanding compensation for lost profits from the North Caspian Operating Company (NCOC), the consortium that manages the Kashagan oil field, and arbitration claims have risen to $150 billion. Sources close to Kashagan told The Times of Central Asia that this should send the message to western energy companies that Kazakhstan is looking to revise previously signed contracts. While Bloomberg has reported the sum of the claims, citing people familiar with the matter, Kazakh government officials have declined to comment on the situation, claiming that it is a "commercial dispute." In April 2023, proceedings against the companies developing the Kashagan and Karachaganak fields began as part of a dispute over cost deductions from oil-sale proceeds of more than $13 billion and $3.5 billion, respectively. An additional $138 billion claim relates to the calculation of the cost of oil production "that was promised to the government but not delivered by the field developers," according to Bloomberg. The Ministry of Energy has not yet commented on the new claims. It states that the Kazakh authorities seek to maximize profits from their oil-production projects with the participation of foreign investors, but have been relatively flexible in previous disputes with oil corporations. International sources note that Eni, Shell, Exxon and TotalEnergies have already invested around $55 billion in Kashagan, and currently the field produces about 400,000 barrels of oil per day. NCOC investors, led by Italy's Eni, are convinced that production can be increased to 1.5 million barrels per day. NCOC has stated that it acts in strict compliance with the contract. Representatives of Eni confirmed that the Kazakh authorities have applied to the court for arbitration settlement, but did not disclose details. Earlier, Kazakhstan won a lawsuit against the Kashagan consortium which required them to pay $5.1 billion for damage to the environment. Kashagan is developed by the NCOC consortium, which includes the national company KazMunayGas (KMG) and several foreign energy companies: Eni, Shell (Great Britain), ExxonMobil (USA), Total (France), Inpex (Japan), and CNPC (China). Member of the Public Council of the Kazakh Ministry of Energy, Olzhas Baidildinov believes that the sharp increase in the amount of the lawsuit is a signal from the Kazakh side to the consortium to revise the contracts. "In my opinion, it's obvious that Kazakhstan wants to revise the terms of work on large consortia. At the same time, I have proposed many times to exchange the frozen assets of the Russian Federation for stakes in major projects: Tengiz, Karachaganak and Kashagan. There is a nuance here: for example, the shares in Karachaganak and Kashagan are managed by PSA LLP, which is determined by the authorized body, while the share in Tengiz is managed by KazMunayGas. As we see, on Kashagan and Karachaganak there are arbitration claims filed in international arbitration, there is an environmental issue - but on Tengiz they are silent for some reason. This is either KMG's unprofessionalism, because the amount of investment expense is very high, or some other unknown issues that need...