What Bank Loan Data Can Tell Us About Kazakh Business in 2023

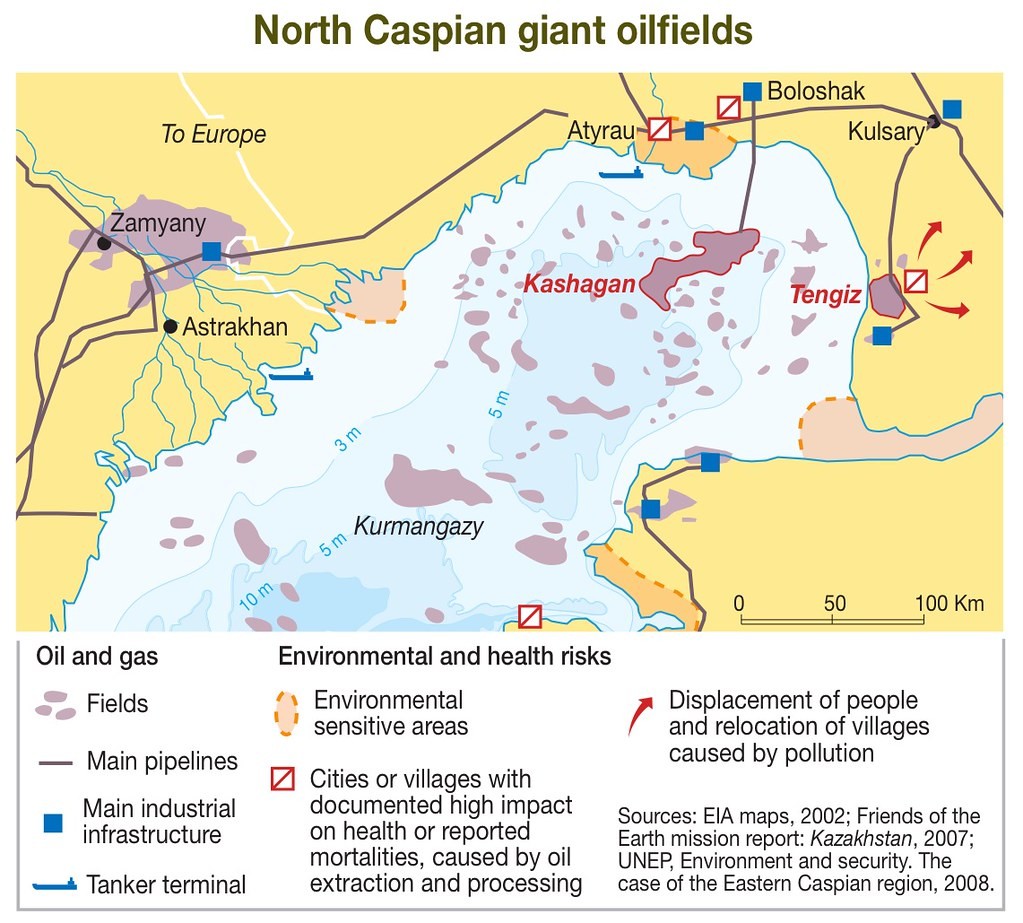

After being severely tested by the pandemic in 2020-21, several thousand companies in Kazakhstan closed due to decreased demand and supply chain disruptions. Though the problems of local businesses began long before the pandemic, the two years of lockdown wiped out many good players and made those that survived more dependent on government orders and projects. Overall, Kazakhstan has a primarily commodity-driven economy (crude oil, metals and petrochemicals account for the majority of export earnings), and the country's economic fortunes have tracked the prices of a short list of major commodity exports. Thus, the government finds it hard to diversify the economy. Oil price volatility affects the national currency, and the ups and downs in the tenge exchange rate versus hard currencies make it difficult to be in a business with an investment cycle longer than one and a half to two years, as you have lower revenues amid dollar investments. This is one of the reasons why launching long-term projects in the country is difficult when there are no guarantees of sales, while currency risks can hit any project. The government has been active in attracting foreign investment, offering state support and protection, but only relatively recently did it begin to pay the same attention to the demands of domestic investors. However, this is only the beginning of a very long journey towards reducing dependence on imports and expanding the range of exports to stabilize the economy. A debt-driven economy The share of the private sector in Kazakhstan is difficult to measure. If we take SMEs (small to medium-sized enterprises) as the core of private business, in different years it fluctuates between a range of 20-30% of GDP. However, since state capitalism is entrenched in the country, even among SMEs there are contractors working for state and quasi-state structures, receiving funds from state companies and agencies. One-hundred-percent private companies that do not depend on government contracts finance their operations from their own or borrowed capital. This is why, in a transparent economy like Kazakhstan’s, looking at loan data can reveal the main trends in business and which niches have not yet been occupied and could be interesting for investment by both foreign and local players. It is best to look at the country's economy through the loan portfolio of banks that are subject to international banking regulation, whose indicators meet an easily understandable standard. There is a caveat: in Kazakhstan there is also the Development Bank of Kazakhstan, which is not included in the table below. It is technically not a bank, but rather a development institution financed from the quasi-public sector by Baiterek National Management Holding, which receives budgetary funds. In addition, most extractive-industry companies in Kazakhstan – due to their high capital expenditures and the shallowness of the country’s financial market – raise funds in the U.K., Switzerland, the U.S. and Russia. Chinese banks rarely lend to 100%-Kazakh companies, limiting themselves to trade credits (in the form of equipment) or loans to joint ventures with Chinese...