The settings were starkly different. An Uzbek honor guard in elaborate uniform greeted Russian President Vladimir Putin after he arrived at Uzbekistan’s Tashkent airport on May 26 for a state visit. Two days earlier, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskiy gave an interview to Central Asian media in his signature army-green combat-ready t-shirt, sitting in the ruins of a Kharkiv printing house destroyed by Russian missiles.

With the war in Ukraine into its third year, Putin’s trip to Uzbekistan represents part of his broader mission to nurture long-standing trade and security ties with Central Asian countries, who have been trying to walk a delicate line in their relationships with Russia. Uzbekistan’s President Shavkat Mirziyoyev welcomed Putin with a literal embrace. Their official meeting the next day was scheduled to address bilateral issues and views on “current regional problems,” reported Russia’s state-run news agency Tass.

While in Uzbekistan President Putin had boasted that Russia was Uzbekistan’s biggest trading partner with export growth by 23% this year and had invested over $13 billion in the country. He called Uzbekistan to be the biggest state in Central Asia; praised Mirziyoyev’s language policy that protects Russian language in schools and as an official language in Uzbekistan. Russia has started exporting gas to Uzbekistan through Kazakhstan, with some of the gas staying in Kazakhstan. Some analysts argue that Russia can circumvent sanctions by partly relying on imports, mainly from Europe, that come through Central Asia.

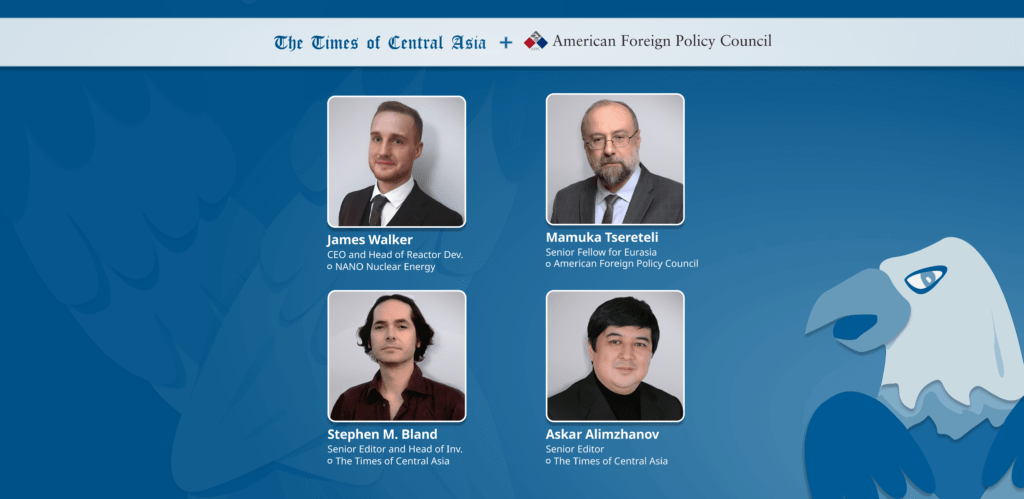

Over in the war-torn Ukrainian city of Kharkiv, President Zelenskiy’s interview with six journalists from Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan, some openly affiliated with Radio Free Europe and the Soros Foundation, included a discussion on how to deepen solidarity between the people of Central Asia and Ukraine over a shared anti-Russian sentiment.

Zelenskiy tells Central Asians to drop their balancing act towards Russia

In the interview, President Zelenskiy challenged Central Asian countries to overcome their economic dependencies and security vulnerabilities and adopt Ukraine’s hardline posture against Russia. The region’s leaders “are still [positioned] more in the Russian direction because of fear of the Kremlin. We [the Ukrainians] have made our choice, we are fighting,” Zelenskiy said, according to a Russian transcript of the interview published by Kazakh media outlet Orda.kz. Zelenskiy told Central Asians and others who are “trying to balance” their relationships with Russia to “not wake the beast” that this strategy will not work because “the beast does not ask anyone: he wakes up when he wants”.

Zelenskiy warned Central Asian people that alongside the Baltic states and Moldova, they, too, face a risk of being invaded by Russia given their Russian populations, which the Kremlin may decide to intervene to protect, as it did in Ukraine. He also added grimly, “if you, your people, resist becoming part of Russia, you will inevitably be waiting for a full-scale invasion, death and war.” Calling on the world to unite against Russia, President Zelenskiy recommended that Central Asians isolate Russia economically and diplomatically, arguing that “balancing acts” to help their economy in the short-term are fleeting whereas values, such as, respect and friendship are “eternal”.

Does Ukraine’s message of solidarity resonate in Central Asia?

The premise of President Zelenskiy’s point – that such widespread hostility against Russia either already exists or can be stirred up among the region’s people – is not at all a given.

The first reason is tangible economic and practical considerations that go much further than the “fear of the Kremlin” presumed in President Zelenskiy’s interview. Russia and Central Asian countries cooperate in multiple international groups such as the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) and the Commonwealth of Independent States. All five Central Asian republics also belong to the Russian-led Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), which provides mutual defense commitments similar to NATO’s Article 5 as well as crisis response mechanisms, and maintains a military presence at bases in Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan.

More significantly, Russia comprises a significant proportion of Central Asian states’ foreign trade. As an example, in 2021, imports from Russia represented 42.5 per cent of Kazakhstan’s total imports. Additionally, the legacy of economic ties and infrastructure from the Soviet Union depends on integration between neighboring countries. Anvar Kuspanov, a 44-year-old lawyer from Kazakhstan, gives the critical example of water reservoirs where Russia’s water discharge can have a tangible effect on the levels of Kazakhstan’s rivers.

Ukraine’s pleas to the West to sever energy ties with Russia proved difficult even for the European Union to implement. Some 15% of the bloc’s gas came from Russia in 2023 while Austrian gas imports from Russia stood at an astounding 98 per cent in 2023. Liquified Natural Gas (LNG) exports from the U.S., Qatar, Nigeria and Algeria have made up for Europe’s shortfalls. Landlocked Central Asia, on the other hand, does not have the luxury of such alternative sources, and their most feasible trade route continues to pass through Russia, at least until the Trans-Caspian Middle Corridor increases capacity. Access deficiencies severely impacted the region’s supply chains, pushing inflation up to almost 12 per cent in 2023 compared to a global average of 6.5 per cent.

The people, for the large part, want their leaderships to focus on pragmatism in world affairs over national sympathies or ideologies. According to Kuspanov, “breaking economic and diplomatic ties with Russia at once would be suicide”, not to mention the adverse effects it would have on numerous economic associations in which these countries participate. “They say, keep your friend close and your enemy closer,” points out Sultan D., a 66-year-old pensioner also from Kazakhstan: “As long as we are in close relations with Russia with a common market, customs, and so on, nothing will threaten us (…) Our country got back on its feet, largely because we had healthy, pragmatic relations with Russia.”

In practice, successful implementation of this balanced pragmatism by Central Asian leaders has resulted in them being criticized by both Russian and Western partners. Nonetheless, it appears to answer public demands. As Marat T., a 32-year-old store owner in Kazakhstan, says, “There should be pragmatism in politics. We have a huge border with Russia and a brisk trade. They produce a lot of quality goods [that] we can’t. So there is no sense in quarreling with Russia for the sake of [demonstrating] friendship with Ukraine, who in principle, did not pay attention to Central Asia all these years”. Adding that he has no sympathy or dislike for either side, Marat summarizes what many of his countrymen may feel: “Ukrainian disputes with Russia have nothing to do with us”.

The second issue complicating Central Asia’s position is cultural and historic ties with Russians. “This is not our war”, Sultan D. argues and adds, “We have different relations with Russia. Kazakhs live there, Russians live here, and we know each other’s culture and customs”. The fact that there is affinity towards Russia and its people in parts of Central Asia risks divisions in the region’s societies. According to Kuspanov, in the northern and eastern parts of Kazakhstan, there are a large number of pro-Russian citizens who express sympathy for Putin. “I believe that it is not tanks and airplanes that we should be afraid of but information and economic pressure that draws Kazakhstan into other people’s conflicts”, warns Kuspanov and adds, “The battle for minds is being waged from all sides – from both the West and the East (…) We are between two fires”.

The third factor is security concerns. In his interview, Zelenskiy posed a question that particularly resonates with Central Asians: “If Ukraine had retained its nuclear weapons, would Russia have dared to attack us?” All Central Asian states are signatories to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) as non-nuclear-weapon states. After inheriting approximately 1,410 nuclear warheads following the Soviet Union’s dissolution in 1991, Kazakhstan chose to denuclearize and dismantled its nuclear testing infrastructure.

“In case of any external aggression, Kazakhstan will need help. But will such help come in time and will it come at all?” wonders Kuspanov. China is becoming a stronger deterrent against possible Russian aggression in Central Asia. One example is the increasing military-technical cooperation and bilateral exercises between China and Kyrgyzstan’s armed forces. China also conducts multilateral military exercises within the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) without Russia, showing its support for the sovereignty and territorial integrity of Central Asian states. Future security cooperation with China is expected to further develop and can even potentially lead to a new pact that guarantees protection against external aggression.

Even with higher hopes of outside support in the face of external aggression, however, it is still better not to agitate the aggressor in the first place. “One should try not to quarrel with neighbors, especially strong ones”, says Sultan D. from Kazakhstan. “People always pay for the mistakes of politicians. Zelenskiy, I remember, promised to end the war in Donbas, but instead he got an even worse war.”

Walking the fine line is the only way, for now

It is clear that various factors such as their integrated infrastructure systems, extensive trade links, existing collective security formats, tens of joint projects, and strong historical and cultural ties put Central Asians in a different position vis-à-vis Russia than the rest of the world. Yet, balances are shifting, albeit slowly, as Central Asian leaders are carefully diversifying their relationships through developing engagements with China, Turkey, and Western nations such as France, Germany and the USA.

To their credit, Central Asian governments have publicly stayed neutral on the war in Ukraine and largely complied with Western sanctions against Russia, even though a handful of Central Asian entities have been slapped with secondary sanctions. Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan have also provided humanitarian aid of $2.25 million and $1 million respectively to Ukraine. In line with its diplomatic position on sovereignty, territorial integrity and international law, Kazakhstan has openly stated that it does not recognize the self-declared Donetsk and Luhansk republics. The country appeared to have paid a price for this principled stance, however, as a Russian court ordered the Caspian Pipeline Consortium (CPC), which utilizes a Russian controlled terminal in Novorossiysk and land for transit, to suspend activity for 30 days. This negatively impacted Kazakhstan’s economy, which relies on hydrocarbons for around 20 per cent of its GDP and uses the CPC for its oil exports.

To date, Ukraine has received over $100 billion, mostly in aid, from the U.S. and its European allies, constituting a lifeline for its defense against Russia’s advancements. Its continuing plight even with such international support, and despite having access to seaports (an advantage Central Asian states lack), is a stark reminder to the region’s countries to keep neutrality, prioritize diplomacy over conflict and firmly stand to protect multilateralism.

In the end, Central Asian states will act in their own best interest, and for the moment, that includes keeping the delicate balance that Zelenskiy wants them to abandon. In his interview with Central Asian journalists, President Zelenskiy said, “I focus on what unites us rather than divides us”. At a time of immense external pressure from all sides, Central Asian leaders are also choosing to focus on the unity and welfare of their own communities.