The UN General Assembly’s Human Rights Council recently condemned the government of Tajikistan for its failure to implement the recommendations of a 2019 study by UN representatives. The study focused on the unreconciled atrocities and societal wounds caused by the civil war that swept through the republic after the collapse of the Soviet Union. More than 60,000 people died in this war, and more than 250,000 fled the republic. Reading this news, I was reminded of and reflected on post-war Tajikistan, which I visited in the late summer of 2000. At that time, the country had been in a state of fragile peace for two years, and you could still feel the tension in the air.

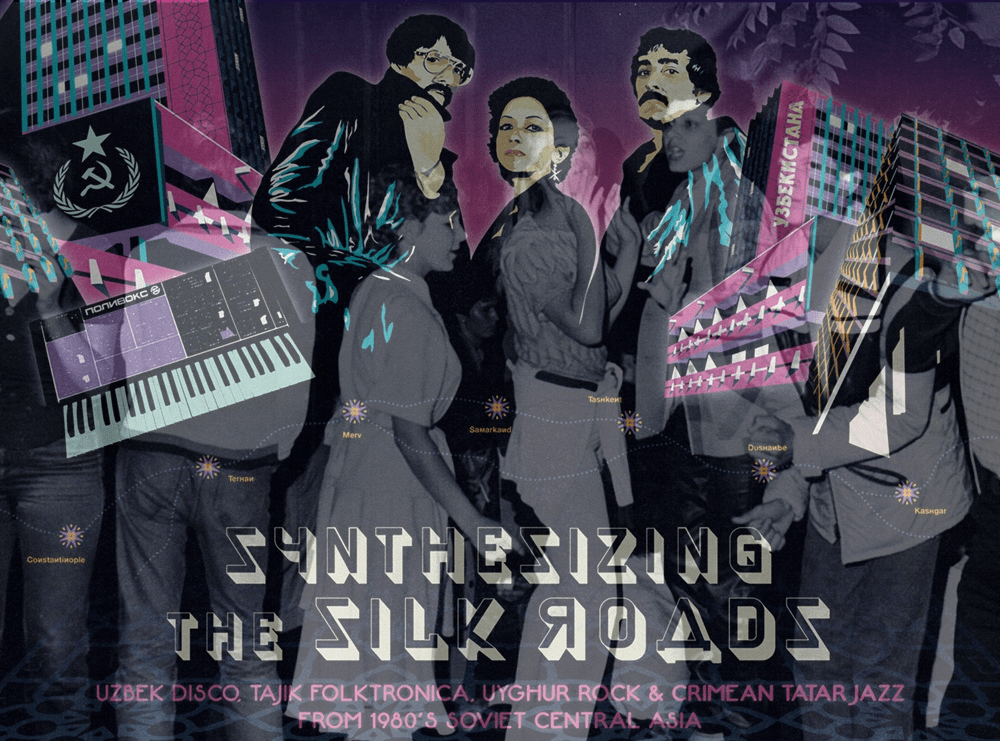

Since my visit to the country in 2000, the Tajik Civil War has been reflected on by many people in the arts. In the same year that UN researchers were raking up the old tragedy, the film Kazbat was released in Kazakhstan. This movie is a military drama about the real deaths of 17 soldiers of the Internal Troops of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of the Republic of Kazakhstan (now the National Guard), who fell into an ambush in Tajikistan on April 7, 1995.

A little earlier, in 2017, Russian writer Vladimir Medvedev released the novel Zakhok, which talks about the horrors of that six-year war through the struggles of a single family, where the mother is Russian, and the children are half Tajik.

My visit to this war-torn country was for a reason most wouldn’t have expected – a comedy festival. The group that I traveled with consisted of my teammates, Almaty residents, as well as people from other Kazakh, Uzbek, and Kyrgyz cities. Despite coming from all over Central Asia, we ended up in Tajikistan for the first international СVN festival (СVN – Club of the Funny and Inventive) in Central Asia.

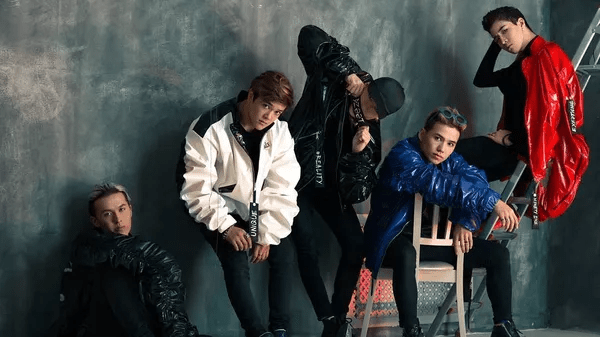

СVN is an improv and sketch comedy competition involving students that originated in Soviet times, the point of which is to satirize the surrounding reality through theatrical skits and question-based improv. Due to its satirical nature, СVN was banned for two decades during the Soviet-era. It was later revived during Perestroika, and, in the shortest possible time, became a phenomenon in all universities in Russia and across almost all of post-Soviet space.

In Kazakhstan, СVN was developed immediately after the collapse of the USSR. Alma-Ata, which was the capital city back then, organized its own league, which included teams from the leading national universities of that time – Kazakh State University, Narkhoz, Almaty Institute of Transport Engineers, and Almaty State Medical Institute.

I belong to the second generation of СVN players. Our task was to popularize this game throughout the republic and attract not only universities but also colleges and schools. Later, the new СVN league went beyond Kazakhstan, starting with friendly meetings with universities from Bishkek, Tashkent, and other Central Asian cities. Then, the International League of СVN, which was created and headed by Alexander Maslyakov, who passed away recently, came to Kazakhstan. The best teams in the country got their own СVN coaches who were famous in Russia. For example, the coach of one of them was Vladimir Zelensky himself and members of his team from “Kvartal-95”.

The Kazakh Super League received from Alexander Maslyakov a kind of carte blanche to attract Central Asian teams to the games of the International СVN League. To attract more teams, an international festival was organized. The idea of holding it in Tajikistan was connected with the task of showing that in this republic, the civil war had finally become a thing of the past.

The festival was not organized in Dushanbe, in the north of the country where it was still rumored to be turbulent, but in the south near the city of Khujand (formerly Leninabad). In Khujand itself, the closing gala concert was held, which ended with a friendly meeting between the teams from Kazakhstan and the other Central Asian republics. The two-day competition of СVN teams took place on the territory of the former pioneer camp near Khujand, on the bank of the man-made Kairakkum Reservoir.

Kazakhstani teams had traveled to Khujand by buses, for which they had to cross the territory of Uzbekistan. A local guide and a СVN player from Dushanbe Medical University got on our bus at the border with Tajikistan. He introduced himself by the name Abdullo, which he had been given when he converted to Islam. He did not give his “secular” name.

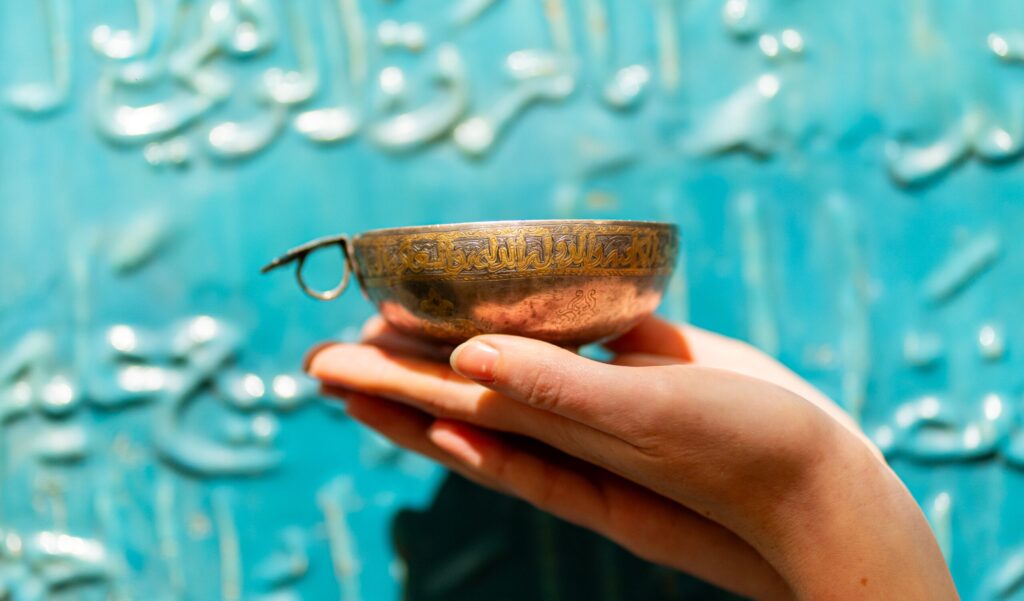

For Kazakhs, whose republic had made significant progress in creating a secular and even anticlerical state during the Soviet era, the Tajik fascination with the Muslim religion seemed unusual at the time. Abdullo quickly explained to the boys on the bus that they should change from shorts to pants. Some of us tried to protest – the heat outside the bus was approaching 40 degrees Celsius – but Abdullo pointed to a man in camouflage carrying an automatic rifle who was standing on the road just beyond the Tajik checkpoint. At first, we thought he was a border guard who had grown his bushy beard for some reason.

“He may shoot,” Abdullo warned us; ”he’s from Mastchoh, they are Islamic fanatics.”

After that, even the most stubborn quickly changed their clothes.

On the road to the Kairakkum Reservoir, we saw fields where cotton once grew, but now they bore nothing but stones and scorpions. Abdullo told us about the people from Mastchoh, who had suffered greatly during the Soviet period because of cotton. In 1956, the Soviet authorities organized their resettlement, during which many of them died.

In one of the settlements, we came across a traffic light. Each of its three “eyes” was covered with bars, and the traffic light was not working.

“The consequences of the war,” Abdullo explained to us.

However, when we finally reached the pioneer camp, we felt nothing of the sort. The neatly cleaned territory, the buildings with beds covered with snow-white linen, and an abundance of food — all this made us forget for a while that we had come to a war-torn republic. However, we were constantly reminded of this when talking to the locals, especially those in Dushanbe. It seemed that each of them carefully evaluated their words before answering any questions. Abdullo, with whom we became friends during the journey, explained that this was also a consequence of the war.

“We don’t want any more conflicts, especially because of carelessly spoken words,” he said, warning us not to talk to Dushanbeans in particular. “They suffered a lot during the war, and post-traumatic stress syndrome can manifest itself at any time. And you Kazakhs don’t watch your talking at all,” he said.

However, there were no conflicts during our time there, and during the festival the Tajiks seemed to thaw, laughing with pleasure at any, even the silliest jokes that came from the stage.

The gala concert in Khujand (а city founded over 2,500 years ago) caused a real sensation. It was held in a local theater with excellent acoustics and a perfectly equipped stage. Our team performed with a short program of 5-7 minutes, but because of the incessant applause, the time of the performance doubled. Everyone, from those sitting in the hall and those standing backstage, seemed to sing along to the final song.

After our performance, we went outside, escaping the heat and stuffiness of the auditorium. Sitting on the steps of the porch of the theater, we ate pomegranates that had just been picked and marveled at how fertile this land is and what people have changed it into.

Leaving the republic, we sincerely wished it happiness and prosperity. But this, alas, has not happened. But, perhaps it still has yet to come.