The seventh largest city in Uzbekistan, the history of Bukhara is swathed in legends which stretch back for millennia and can be traced to the period of Aryan immigration into the region. After passing through the hands of Alexander the Great, the Bactrians, the Kushan Empire and many others, Bukhara became an epicenter of Persian culture in medieval Asia. With the rise of the Caliphate, by the end of the ninth century Bukhara was one of the most significant Islamic and cultural sites in the region. Throughout its history, Bukhara has been nourished by merchants and travelers, establishing itself as a major hub of trade and crafts on the Silk Road.

Today, in the orange early morning light, women holding parasols walk their children to school down gravel alleyways to the ever-present hum of air-con units. Broom-wielding figures in high-viz orange jackets cast bulbous shadows as they sweep the dust from side to side. As the sun arcs towards its zenith, a haze develops, the heat so overpowering that even the hawkers lose the will to sell.

Weaving past scant pedestrians, infrequent marshrutkas head out of town towards the glittering Summer Palace of Bukhara’s last Emir, the outsized Sayyid Mir Muhammad Alim Khan. Beyond the imposing majolica tiled gateway of the Russian-built Sitora-I Mohi Khosa – Palace of the Stars and the Magnificent Moon – the banqueting hall contains an elaborate bronze chandelier from Poland weighing half a ton. To gasps of awe, Bukhara’s first electric light shone from it during the 1910s thanks to a fifty-watt generator.

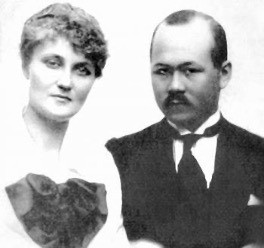

An avenue of quince trees leads to an ostentation of peacocks parading around a voluminous pool, where the Emir’s harem used to frolic. Raised on a platform high above them, the Emir would sit upon his gilded throne, bejeweled and decked in golden threads, choosing his lady for the night. Escaping the conflict between reformers and imams, and ever more dependent upon the overlords who would inevitably bring about his downfall, Amir Khan spent his last years as ruler cocooned in the Summer Palace, sating his gluttonous appetite from a glass-fronted Russian refrigerator.

Putting his lot in with the reformers, then switching sides in the face of the mullah’s power, in his final years the last Emir was a leaf in the wind. These were the dark days of mass executions, book burnings, and an intellectual exodus from the Emirate. When the ripples from the Bolshevik Revolution reached his kingdom, Alim Khan declared a Holy War upon the Russians and their reformist allies, the Young Bukharans. With Russian gunners initially forced back by frenzied, knife-wielding true believers, tit-for-tat retributions took place before, with their inevitable victory sealed, the Red Army set about pillaging and murdering their vanquished foes. On September 2nd 1920, soldiers raised the Red Banner from the bombed-out lantern of the Kalon Minaret.

From the ninth-century Pit of the Herbalists to the Ismail Samani Mausoleum, Bukhara isn’t about its separate sights, though, it is the sum of its parts, a timeless city permeated by an air of antiquity. On cobblestone back alleys, decked in dopys – four-sided black skullcaps – striped robes and knee-length rubber boots, revered white-bearded elders idle the afternoons away over pots of choy. From terraces where their mothers hang lines of laundry between buildings, the playful cries of children ring out by the Kalon Minaret.

Built as an inland lighthouse for desert caravans, the Kalon Minaret – ‘great’ in Tajik – was almost certainly the tallest building in Central Asia upon its completion in 1127. The third minaret to have been built on this site, previous incarnations had caught fire and collapsed onto the mosque below, officially because of the ‘evil eye’. Also known as the ‘Tower of Death’, over the centuries the minaret has seen countless bodies sewn into entrail catching sacks and tossed from its 47-metre-high lantern. Particularly popular during Mangit times, this practice survived until the 1920s.

Home to the first recorded use of the now ubiquitous blue tile in Central Asia, the fourteen distinct bands of the minaret are majestic in the pink light, its scale and intricacy remarkable. But despite the lingering sense of history, everyday life goes on unabated at its stout base. Traders hawk their wares, and when the heat of the day finally abates, head-scarfed babushkas sit chit-chatting on the cool stone steps of the Mir-i-Arab Madrassa. In the square around them, children bounce beach balls off the hallowed walls, as above them doves circle the Madrasa’s crescent moon.

Seven times rebuilt upon the ruins of its predecessor, at the northern edge of town, the Ark – the former Royal City – had grown ever higher with each new incarnation. Of mythic origins, the Ark of Bukhara dates back to at least the fifth-century AD. When it was leveled in an aerial bombardment ordered by the Bolshevik General Frunze in 1920, the planes that reduced it to rubble were the first most Bukharans had ever seen. What survived the blitz was ordered destroyed by the fleeing Alim Khan. Shortly to be safe in exile in Tajikistan with the city’s teeming coffers, the Emir bade that his harem should be blown-up lest the Bolsheviks desecrate it. It is unclear whether the women of the harem were still inside at the time.

The last vestiges left by Alim Khan’s beks (governors) after he fled, Southern Tajikistan is littered with ruined Bukharan garrisons. Escaping to Dushanbe – then just a village – Alim Khan sought international support, but found no backers. With the Bolsheviks advancing, his Basmachi (bandit) Army of Islam riven by infighting, and his requests for aid having gone unanswered, the last Emir floated across the Pyanj River to Afghanistan on a raft made of wood and sheep-gut, never to return to his homeland.