Space continues to capture our imagination and inspire our stories, as we try to make sense of this vast final frontier. In the last part of our series on Baikonur, we explore its depiction within cinema. In 2011, German filmmaker, Veit Helmer released Baikonur, a story about space, scavenging and misguided love that was shot within the region. TCA spoke to him about filming in this heavily restricted landscape.

TCA: What was the inspiration behind your film, Baikonur? What drew you to this subject matter?

Helmer: I was fascinated by the actual place, or what I knew about it; a hidden city with such a glorious past. Whilst researching, I found out about the scavengers who collect the pieces which fall on the steppe when the rockets are heading to space. To tell both stories at the same time intrigued me: space exploration and hunting for scrap metal.

TCA: Given you also directed Absurdistan and Tuvalu, would it be fair to say you’re drawn to far-flung places?

Helmer: Yes, I love to explore and find locations which haven’t been filmed before. But compared to the locations of my previous films – Tuvalu, which was shot in Bulgaria, and Absurdistan, which was shot in Azerbaijan – to travel to Baikonur was a much longer journey.

Still from the film, “Baikonur,” Alexander Asochakov as “Gagarin” leaving, villagers standing near yurt; image: Veit Helmer

TCA: As stated in the tagline of your film, “Whatever falls from heaven, you may keep. So goes the unwritten law of the Kazakh seppe. A law avidly adhered to by the inhabitants of a small village, who collect the space debris that falls downrange from the nearby Baikonur space station.” The village scavengers portrayed in your film are based in reality; how did you find out about them, and what was your experience with them?

Helmer: It was very funny reading the first review from Kazakhstan, where a young journalist wrote that the film is based on the old Kazakh law “Whatever falls from heaven, you may keep,” which in reality was an invention by my screenwriter, Sergey Ashkenazy. But as this fable seems to feel so real, I never tried to dispel that myth. When writing the screenplay, Sergey and me went to Zheskaskan and the surrounding steppe, talking to the hunters of the scrap metal. It was not an ideal moment, because Roscosmos started to collect the debris themselves and the local villagers’ activity became illegal. The new reality was not villages against each other, but villagers against Roscosmos.

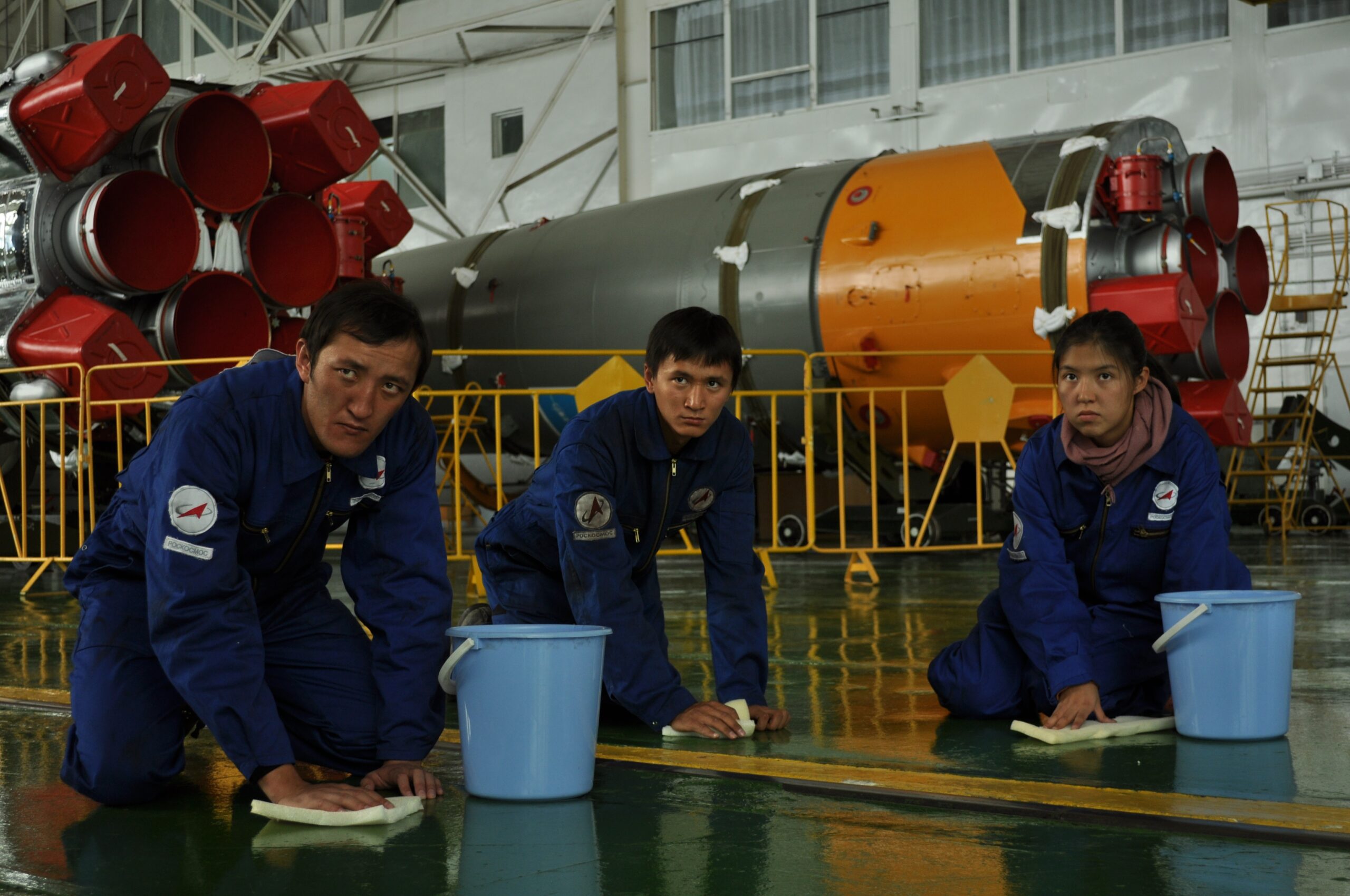

Still from the film, “Baikonur,” Alexander Asochakov as “Gagarin” (center) cleaning assembly hall in Baikonur ; image: Veit Helmer

TCA: As a Western filmmaker you were granted a unique opportunity to film within Baikonur – what did you observe of the landscape? What were the highlights of this experience?

Helmer: There was a saying among the early cosmonauts that the Central Asian steppe was for them like a huge ass and in the middle was the hole, Baikonur. Today, the superiors from Moscow still come two days before the launch and leave the day after. The launch is what makes that ground holy. Suddenly, the Earth becomes sacred and humans watch the miracle of two or three people heading to the ISS. There is no depiction or description which can evoke what it feels like seeing a rocket taking off and heading into orbit.

Still from the film, “Baikonur,” Marie de Villepin (as “Julie”) waving good bye in front of rocket; image: Veit Helmer

TCA: Did you have any difficulties filming in the area?

Helmer: We had huge difficulties obtaining the shooting permits, which were all solved by my producer, Anna Kachko, Gulnara Sarsenova and Andrej Bulatov. The shoot was full of surprises. One day we weren’t allowed to be inside the commando bunker, the following day we weren’t allowed to be outside. I had a very flexible crew, and we kept flipping the shooting schedule.

TCA: The scavengers salvaging space scrap in your film depicts the contrast of an ancient nomadic society interacting with the very futuristic space age; how did they interact with each other? Was it a seamless existence, or were there pitfalls in this arrangement?

Helmer: We weren’t able to have real scavengers in front of the camera. Also, they weren’t collecting the debris anymore as Chinese traders offered them buckets of money for the precious metals. We built a village near Kapchagay on a slope. There was the infrastructure we needed to accommodate the international crew and cast.

Still from the film, “Baikonur,” Sitora Farmonova as “Nazira” riding in front of a monument in Baikonur; image: Veit Helmer

TCA: Many times, a location can be seen as a character within the film evoking mood, like LA and film noir, for example. Would you say the actual landscape of Baikonur was a character in your film? If so, who was this character? What did they feel or bring to your film?

Helmer: I would say the village we constructed – with real rocket pieces – evoked the clash of the rural peasant lives with the high-tech space era.

This is part three of a three-part special on Baikonur. To read part one, click here, and to read part two, click here.

Find out more about Veit Helmer’s “Baikonur” here.