As a DJ, radio podcaster and music enthusiast, I love discovering hidden retro gems like Nuggets-style compilations. There is an unspoken agreement on an era’s sounds depending on the artist’s breaking into the mainstream at the time. Then there are the obscure cuts and one hit wonders that for some reason didn’t make it big upon release, but dated well or were ahead of their time and found an audience at a later date. On other occasions, it’s about geography; if it had been premiered in a different part of the world, it would have been successful or far more celebrated than it was. In my search for such sounds, I feel it shouldn’t be limited by location; good music has no boundaries.

Yalla band, commemorative stamp, Uzbekistan, 2021

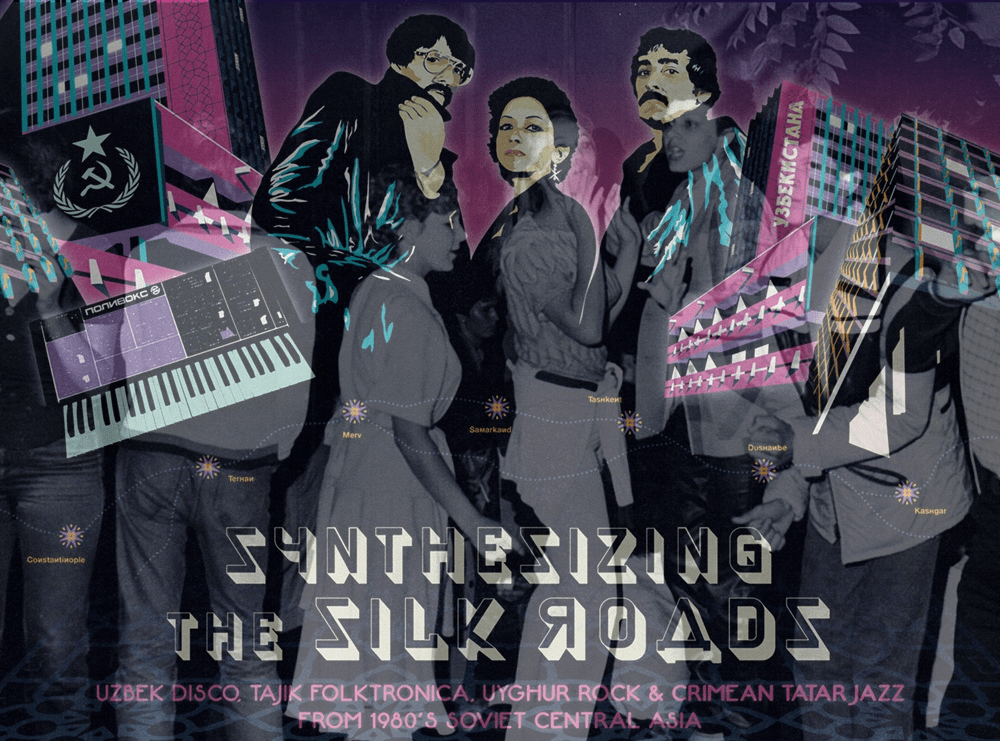

There are many compilations touching upon niche genres and moments in time which can transport one to sonically experience a particular era. As a Westerner trying to peek behind the Iron Curtain to gauge the music and arts scene of the 1970’s and 80’s, what flickered across the Cold War barriers seemed controlled, state-approved, and mostly a mystery. It was a delight to learn that under this supposed monochromic blanket, a dynamic underground music scene was flourishing in regions that had a long history of cultural fusion. SYNTHESIZING THE SILK ROADS: Uzbek Disco, Tajik Folktronica, Uyghur Rock & Crimean Tatar Jazz from 1980s Soviet Central Asia features musicians from countries such as Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and Kazakhstan, who were creating a unique sound that stood apart from anything else being produced in the USSR. TCA spoke to Ostinato record label boss Vik Sohonie about the release.

TCA: How does this statement by Peter Frankopan quoted in your liner notes – “The bridge between east and west is the very crossroads of civilization” – relate to or define the music you chose?

The music itself is the greatest evidence we have to this argument, because you can hear the cultures of Europe, South Asia, East Asia, West Asia – the Middle East – all mixed into it. Indeed, Central Asia was influenced by all of these regions musically given its unique geography, but it has also influenced the cultures of so many of those parts of the world. During the era of the Silk Roads and the “golden age” of the region, its musical theory, as stated in the liner notes, influenced the music of Europe.

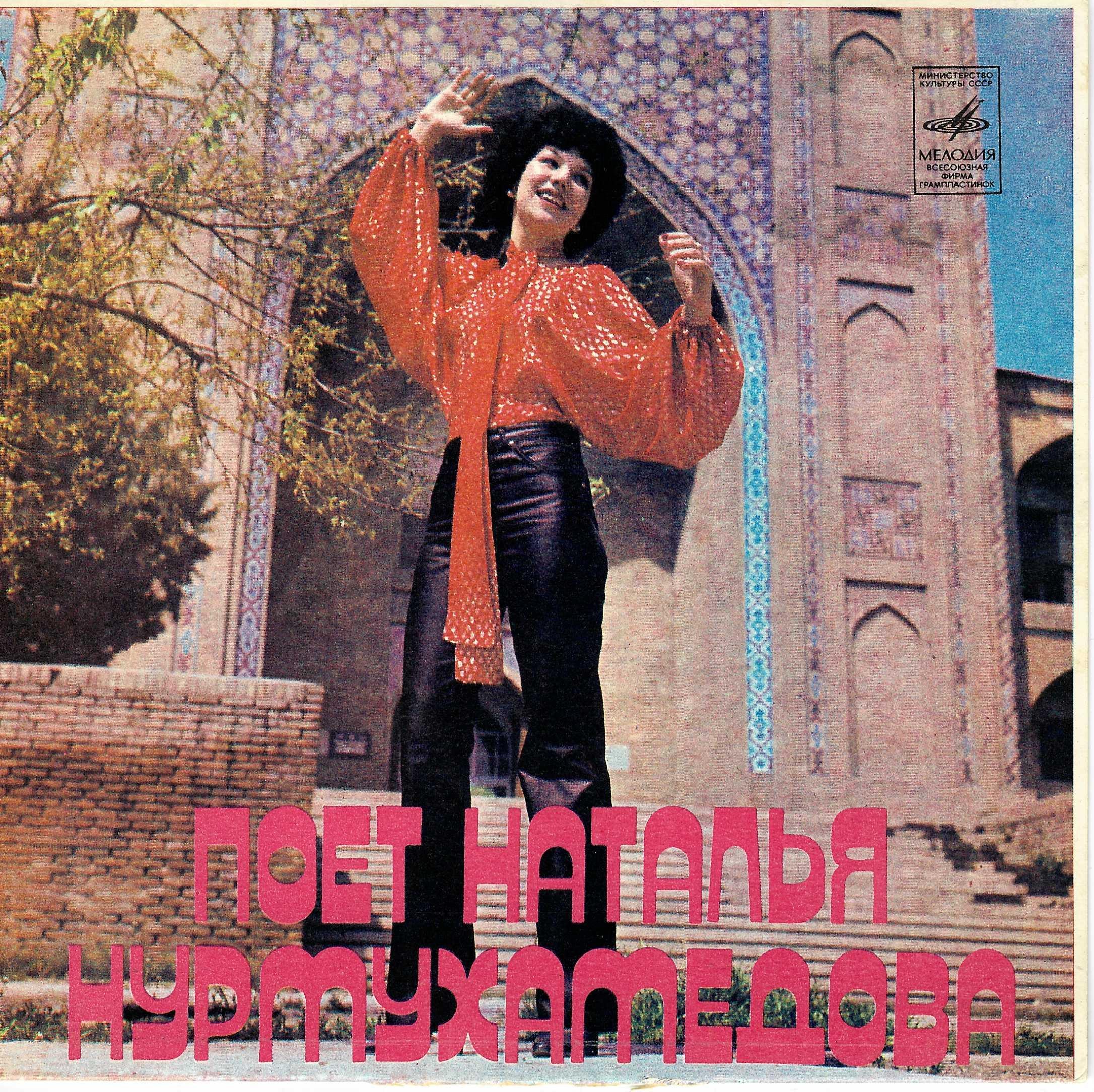

Natalia Nurumkhamedova album cover

TCA: How did World War II and Stalin create the circumstances behind the Tashkent and Uzbekistan scene?

When the Nazis invaded the Soviet Union, Stalin put the best and brightest minds on trains bound for Soviet Central Asia, mainly Uzbekistan and its capital, Tashkent. There were recording engineers on board who went on to set up one of the biggest press plants in the Soviet Union that produced millions of records. A little-known story of World War II – the evacuation from the Eastern European front to Central Asia set in motion what would later form the tracks that make up this album.

TCA: Nikita Khrushchev was important in fostering a new creative drive and easing of censorship within the Soviet Union. Jazz, which Khrushchev compared to “having gas in the stomach,” was the biggest winner in the new, less restrictive atmosphere; can you explain how jazz was important?

Jazz was seen as a tool of American subversion, and perhaps with good reason. Jazz was used by the United States during the Cold War as a way of spreading the gospel of the United States and combating the reality of racism that defined the image of the U.S. amongst many post-colonial nations. A distinctly Black American art form, jazz was both a cultural export and a tool of statecraft – this is how the Soviets viewed it. Nevertheless, jazz’s power made its way to the cities of the Soviet Union and jazz clubs were the first outlets that sprung up in the 50s and 60s that then allowed rock and disco clubs to take shape.

TCA: Why and how did the music in the Tashkent scene move away from Soviet norms?

As a sanctuary city, a safe haven for artists from across the Soviet Union, given its millennia-old reputation as a welcoming hub, there was a freedom within Tashkent that perhaps artists in Moscow didn’t enjoy. But as mentioned in the liner notes, one of the women artists declared that Uzbekistan’s time as a Soviet republic was a golden era for the arts and music.

TCA: How did the “Deep Purple Generation” and disco play a role in the USSR’s unraveling?

Disco and rock clubs became the equivalent of, let’s say “free trade zones.” This is where Soviet censors and doctrine couldn’t control the message or the business model. Within these clubs, private and illicit commerce thrived, Western norms, sense of fashion and music also found a receptive space. This opened imaginations and allowed new ideas to influence the Soviet youth, many of whom developed pro-Western attitudes, and some went on to become leaders of ex-Soviet republics, reorienting them towards a more Western aligned stance.

TCA: You suggest that “discos had become a space for early alternative culture, as well as private commerce” in the Soviet Union, and I love the term “disco mafia”. Can you elaborate on this mafia and how disco was both subversive and advocated commercialism?

Because there was so much money being made at these discos – from the sale of alcohol, cigarettes, possibly even drugs, as well as Western clothing, music and other paraphernalia – a mafia emerged to profit off the revenue streams. It can also be argued that the powerful mafias that emerged in Russia and elsewhere in the former Soviet Union after 1991 found their nascence in these disco clubs, building networks to the West and understanding how to create captive markets they could control and profit from.

TCA: Given the time period and the political backdrop, some of the artists on the compilation have pretty tragic stories; when did you become aware of that and can you tell us more about it?

The more tragic stories were gleaned from our interviews with the artists or their families, and from newspaper clippings that we found from the era that details their arrest, torture, detention and the like.

TCA: I was fascinated by Enver Mustafayev, the “founder of Minarets of Nessef and an ethnic Tatar whose music had an American touch and often included lyrics in Crimean Tatar, a criminalized language;” why was this language criminalized?

Crimean Tatars consider themselves the indigenous people of Crimea and have long advocated for an independent state, one in which Tatar would be the official language. Since Tatars did not form a great deal of the leadership in Moscow or among the secret police, communication in this language could be (and was used) to foment separatism, according to the Soviet authorities. Hence, it was criminalized.

TCA: “More than a sanctuary, Tashkent was a crucible of sound. Nestled between Europe and Asia, its legacy as a key hub along the ancient Silk Roads gave it a cosmopolitan flair for centuries. As a mainstay of Soviet recording, it welcomed artists from across the Asian expanse of the USSR, like Uyghur bands from Kazakhstan via Xinjiang in western China.” Can you elaborate on this?

The sound you hear on the record is not only a sound that was formed during the Soviet era, but the sound of Uzbekistan and Central Asia is distinct and houses many cultures given that travelers and traders have been traversing the region for centuries to move peoples and goods between Europe and Asia. During this ancient trade, musical ideas also left their imprint.

In the Soviet era, Tashkent was a sanctuary, and artists found a welcoming home and a sense of creative freedom. So, Uyghurs, Kazakhs, Tajiks, Tatars, Koreans, and many ethnicities that formed the rich ethnic tapestry of the Soviet Union made Tashkent something like Brooklyn, London, or Berlin today. Tashkent opened its doors to everyone without exception, from our research, and this gave rise to the rich music scene we tried to capture.

TCA: Some musicians, like Davron Gaipov, founder of the cult Uzbek band Original, faced harsh punishment during routine law enforcement at the height of the disco club era in the 1980s. Despite being a “disco divo,” Davron was incarcerated in a hard labor camp in the Ikurst region of Siberia for five years on charges of “repeatedly organizing events accompanied by the use of alcohol and narcotic substances.”’ In the U.S., where disco originated, it was considered a musical movement associated with black and queer/LGBT artists and clientele. Was that the case in the Soviet Union? Were there similar prejudices in the Soviet Union towards non-ethnic Russians or Central Asians? Did disco offer more opportunity for Central Asians to excel against any such prejudices? Was there an early gay culture associated with Soviet and Uzbek disco? If so, were artists or people involved in the scene also persecuted for their sexuality by the Soviet Union?

We did not come across any information regarding the LGBT scene in Soviet Uzbekistan, nor did the artists discuss this.

As for attitudes and prejudices – this is an interesting phenomenon in the Soviet Union. It did not share the rigid racial hierarchies that exist in the United States. In fact, one of the legacies of the Soviet Union in Uzbekistan was a strong culture of anti-discrimination when it came to things like getting a job or renting an apartment. Musically, there was a political imperative to celebrate all cultures in order to create a strong connected identity within the Soviet Union to prevent separatism, which was a constant risk given the sheer size and diversity of the USSR.

Having said that, this is in practice, but one would be lying if they said there was no discrimination or there wasn’t some sort of ethnic stratification. It just did not operate, or perhaps was not as severe, as it does in the settler Anglosphere (United States, Canada, Australia, etc.). The Soviet Union also had a history of aiding countries in Africa, Asia, and Latin America in their liberation struggles as well as educating their youth at universities, so it had garnered a reputation in many non-Western countries as a tolerant society. From our time in Uzbekistan, one of its most endearing qualities was its sheer diversity and what we saw as a strong sense of national identity that surpassed ethnicity.

TCA: Can you tell us more about the Tajik women artists?

Tajikistan remains a more conservative country than Uzbekistan, according to what we were told while in Tashkent, hence Tajik women artists found greater freedom, appreciation and a more liberal atmosphere across the border. All of the Tajik women artists included on this record came to Uzbekistan to record – which in itself says something.

It’s worth getting this collection for the liner notes alone. They’re meticulously researched, with historical events and political circumstances woven to paint a vivid picture. If you love music and history, and how they form the zeitgeist, this is a must read as well as a must listen. You can buy this amazing time capsule capturing this sonic Soviet underground movement here SYNTHESIZING THE SILK ROADS.

Visit Osinato Records Bandcamp here: www.ostinatorecords.bandcamp.com

Ola is a DJ and radio broadcaster Ola’s Kool Kitchen, and you can listen to her show here.