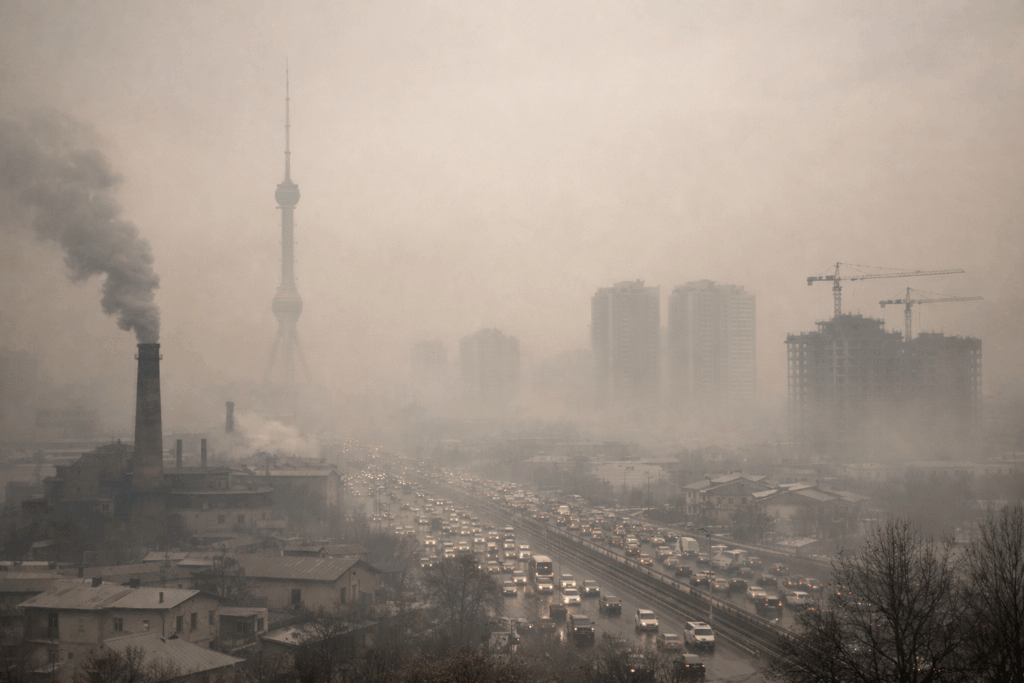

On the afternoon of January 27th local time, the level of PM2.5 (fine particles) pollution in the air in Tashkent surpassed the level recommended by the World Health Organization by 23.2 times, according to data from the U.S. Embassy Tashkent AirNow monitoring station. This ranked Uzbekistan’s capital as the third worst city in the world for air pollution, leading to warnings to “avoid outdoor exercise, close your windows, wear a mask outdoors, and run an air purifier.” Thirty-times thinner than a human hair, PM2.5 particles are widely regarded as the most harmful to health.

Tashkent has been grappling with a serious air pollution crisis for years, and has been consistently ranked among the cities with the highest levels of air pollution worldwide. Several factors contribute to the escalating levels of air pollution in Tashkent. The Ministry of Ecology, Environmental Protection and Climate Change of Uzbekistan has highlighted increasing emissions from coal-burning heat and power plants, motor vehicles, illegal tree felling, and unauthorized construction activities as the key contributors.

The number of vehicles in Tashkent has also increased by 32% from 3.14 million in 2021 to 4.6 million in 2023. The majority of these vehicles use A-80 gasoline, a fuel type that does not meet international standards and emits a significant number of pollutants.

Moreover, coal usage for electricity generation has also increased, rising from 3.9 million tons in 2019 to 6.7 million tons by the end of 2023, whilst Tashkent’s geographical location, surrounded by mountains, exacerbates the problem as it prevents the polluted air from being dispersed by wind.

In response to this environmental crisis, earlier this month the Ministry proposed several measures including banning motor fuel below the Euro-4 standard, restricting the movement of heavy cargo vehicles during rush hours, banning vehicles manufactured before 2010, promoting electric vehicles, reducing congestion by implementing an odd-even scheme for vehicle movement, pedestrianizing city centers, transitioning public transport to electric and gas-cylinder fuel, imposing a moratorium on construction except for facilities of social and state significance, banning the use of coal for industrial purposes in the Tashkent region, and creating a “green belt” around the city.

Despite these proposed measures, with such commitments having been made previously, many remain unconvinced about the government’s commitment to combating air pollution. “It is now safer to live in Chernobyl than in Tashkent,” Journalist Nikita Makarenko wrote on Telegram. “Where are the measures to reduce cars? Where are the paid parking lots; where are the measures to raise the price of owning a car? Where is the public transport?”

Earlier this month, activists in the capital staged a protest to voice their concerns, complaining that the city feels like it is covered in a constant layer of fog which “smells like smoke” and fearing that the government’s response may prove to be a “one-off,” when a long-term strategy is desperately needed.

Tashkent is not alone in the region – earlier this month Bishkek entered the top ten cities globally with the highest levels of air pollution, clocking in at number seven.