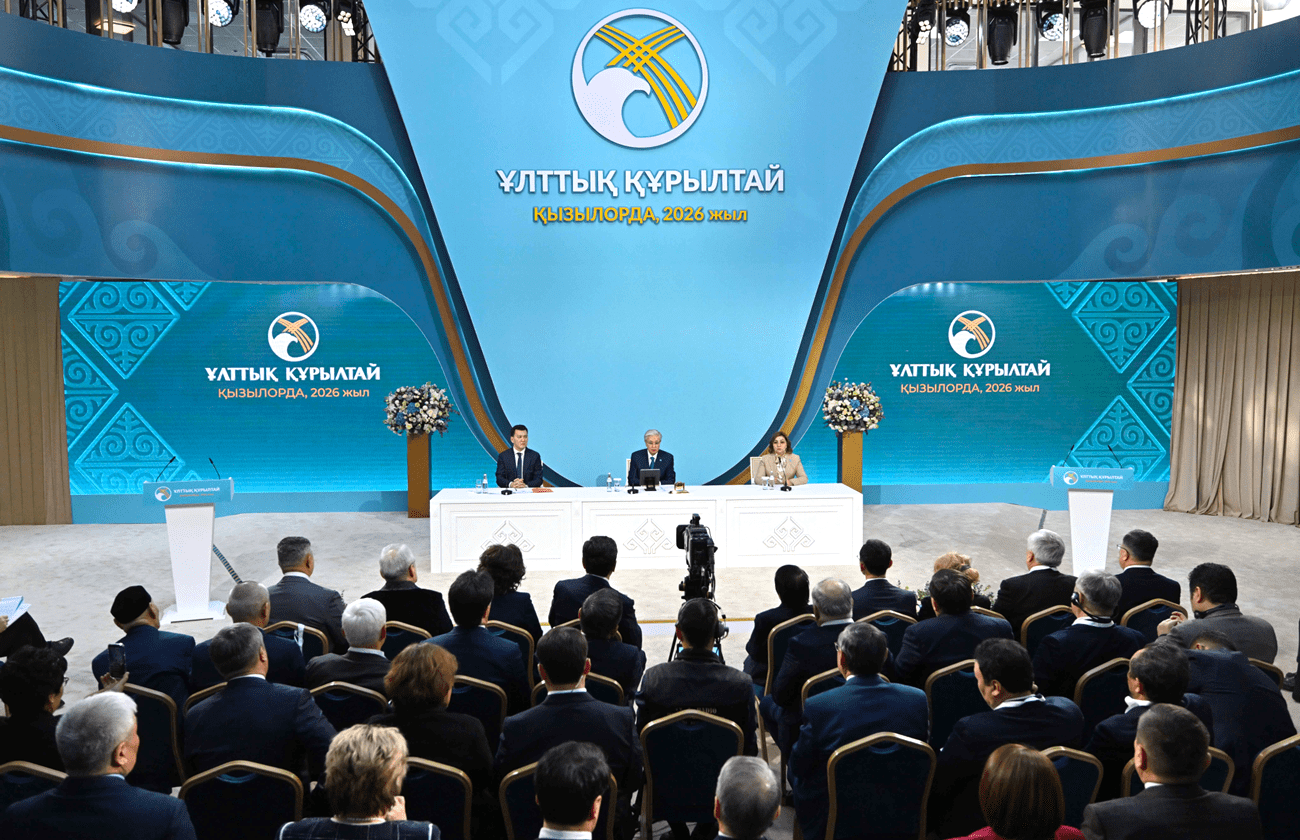

On January 20, 2026, Kassym-Jomart Tokayev, the President of Kazakhstan, addressed the nation at a session of the National Kurultai, an age-old platform for public dialogue, akin to a wise men’s council – at any rate, that’s how it’s often billed. To no one’s surprise, Tokayev pressed ahead with his stated agenda of political reform, highlighting foreign, economic, and development policies and goals. While not devoid of interest, those parts of the speech felt like little more than window dressing that tended to obscure the address’s underlying fire and true import.

Tokayev’s oration seemed at points to echo Alexis de Tocqueville’s ideas in Democracy in America: nations endure only when citizens pair civic participation with moral virtue and personal responsibility, because unchecked individualism ultimately weakens free societies and institutions, regardless of the presence of law and order. On closer examination, Tokayev’s thinking reflects Tocqueville’s view that building democracy is hard but doable. As Tocqueville wrote: “nothing is more wonderful than the art of being free, but nothing is harder to learn how to use than freedom,” pointing towards the belief that nation-building depends on freedom bound to virtue.

Tokayev’s Kurultai message went far beyond a list of technical fixes, platitudes about the economy, and empty cheerleading. Nor did it read as a sleight of hand or bait-and-switch tactic to preserve power in the face of a failing democracy. Those familiar with Tokayev know he has called for Tocquevillian-like responsible citizenship for years, which, to be sure, requires at times tough love.

Tokayev drove home a familiar theme, that the nation’s fate rests on the character and outlook of its people—not just on its economy, wealth, and politics. He maintained that traditional values present the vital adhesive of society, without which, every effort at statecraft withers—or worse, becomes easy prey to unsavory ambitions or certain secular ideologies which have taken on religious force in modern culture.

At the heart of Kazakhstan’s future, Tokayev thinks, there must lie a commitment to enduring human principles and timeless truths: unity, selflessness, sharing, mutual understanding, patience, compromise, and common sense. These values are not solely theoretical constructs but qualities evident for successful outcomes. They positively shape family formation, social relations, conflict resolution, and citizens’ engagement with the state and outsiders.

What’s more, economic and institutional strength is only possible when built upon a society united by common values, clarity of purpose, and a spirit of service.

Transforming Public Consciousness

President Tokayev stressed that changing minds matters more than changing laws and hollow pep talks. Without a common moral compass, nation-building is fragile. Strong cultural and spiritual roots foster social cohesion, building trust, identity, and civic duty.

Towards this end, he urged the older generation “to promote the values of work and enterprise, and wean young people from verbosity, glorification, laziness, indifference, and idleness.”

Tokayev’s strategy for consolidating national consciousness focuses on two core investments: on advancing cultural infrastructure (museums, theatres, libraries) and creative capital, thereby recharging towns and schools as sites of learning, dialogue, and shared identity. He says that celebrations of the country’s national heritage, which should be ideologically neutral, would strengthen self-confidence, facilitate cultural exchange, and promote interstate cooperation.

How does Tokayev want to accomplish this? Paraphrasing the Kazakh philosopher al-Farabi: “Knowledge without proper education is the enemy of humanity. Parenting is primarily the responsibility of parents. However, parents frequently set a poor example for their children. Some are indifferent to the issues concerning child upbringing, shifting all the responsibility to schools and teachers.

“The main source of wealth for the state is people, its citizens. This is obvious. In any case, parents are the ones who open the door to this world for their children. They do this for themselves, not for the state or for society. As a result, every parent should prioritize the development of a responsible generation.”

In other words, starting at the family level, citizens require a proper upbringing, rejecting selfish individualism for common good patriotism.

Tokayev also signaled that foreign actors are obstructing Kazakhstan’s nation-building—not to deflect blame from internal problems, but to caution against destabilizing external interference. “Today, we are witnessing an unprecedented rise in international tensions. Some large countries are trying to literally dictate their agenda, to impose their standards. Moreover, the clash of various ideas and approaches, often diametrically opposed, is now taking place not only in the sphere of geopolitics or economics, but even within culture and spiritual values, in other words, ideology. This is fraught with the most serious negative consequences for the secure coexistence of several states and peoples. The international situation is far from encouraging; therefore, the Republic of Kazakhstan should be united like never before.”

Tokayev’s National Kurultai address was more spiritual than political. It was anchored more in common sense than in power dynamics. It was more about the need for magnanimity – shaped by enduring values, shared purpose, and responsible liberty – than about small-mindedness, narrow thinking, pettiness, and a nihilistic outlook.

Whether Tokayev borrowed ideas from Tocqueville is unclear, but they seem to be on the same page; Tokayev could just as well have quoted Tocqueville in his National Kurultai address. As the French political thinker wrote: “There is no country in the world in which everything can be provided for by laws, or in which political institutions can prove a substitute for common sense and public morality.” Amid unfinished reforms, is Tokayev nudging the nation toward a Tocquevillian worldview, albeit one dressed in a Central Asian chapkan – the traditional long quilted coat of the region?

Time will tell if he succeeds.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the publication, its affiliates, or any other organizations mentioned.