The 2025 Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) Summit, which convened in Tianjin (also known as Tientsin) in China from August 31 to September 1, was the largest in the bloc’s twenty-five-year history. It gathered more than twenty heads of state and institutional leaders, among them China’s Xi Jinping, Russia’s Vladimir Putin, India’s Narendra Modi, Pakistan’s Shehbaz Sharif, Iran’s Masoud Pezeshkian, Kazakhstan’s Kassym-Jomart Tokayev, and UN Secretary-General António Guterres. The agenda ranged widely: counterterrorism, supply chain resilience, energy transition, and climate cooperation all featured.

For Beijing, the event was the centerpiece of its SCO presidency. Chinese officials cast it as a demonstration of “true multilateralism” at a time when protectionism and bloc politics are resurgent. The summit’s final product, the Tianjin Declaration, mapped strategic priorities to 2035. It stressed four pillars: collective security, economic integration, digital transformation, and sustainable development. Underpinning this ambition was trade estimated to be worth over $512 billion between China and SCO members in 2024, illustrating the economic weight now embedded in the organization.

Over the past year, Kazakhstan’s policy entrepreneurship has heightened the significance of its spell as chair spanning 2024-2025. The country’s prominence derives not only from these initiatives but also from its structural position as the largest economy on the Caspian Sea, endowed with the world’s largest reserves of uranium and significant critical minerals. Thanks to its successful implementation of a multi-vector foreign policy aligning with its national strategy priorities, including new energy and transportation agendas, Kazakhstan was able to consolidate its leadership profile.

Policy Initiatives and Prolific Activism

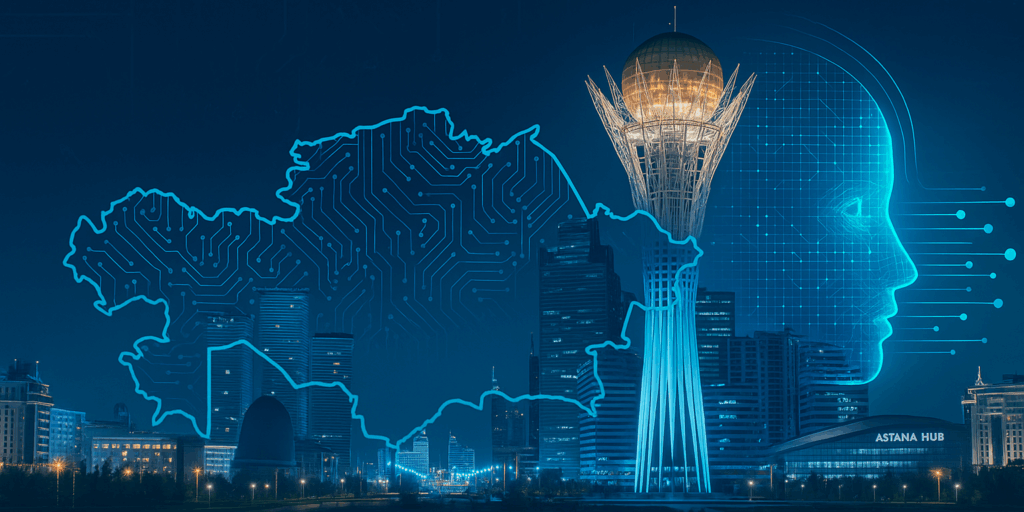

As one of the six founding members, Kazakhstan had chaired the SCO through 2024. At the 2024 Astana Summit, Tokayev unveiled initiatives that set the foundation for Tianjin. He called for the establishment of a UN Regional Center for Sustainable Development Goals in Central Asia and Afghanistan, arguing that the region’s fragility requires a dedicated UN presence. He also proposed an International Agency for Biological Security, intended to manage risks exposed by the pandemic era, and the creation of an SCO Investment Fund to finance joint projects in infrastructure and technology.

During that year, Kazakhstan organized over 140 events in security, economic, and cultural fields, a scale that exceeded most previous chairs. This activism reinforced Astana’s image as a policy entrepreneur within Eurasia’s multilateral institutions. Energy cooperation emerged as the most concrete innovation. In 2024, under Kazakhstan’s presidency and at its motivation, the organization produced a new “SCO Strategy for Energy Cooperation to 2030” committing members to mutual coordination not only in hydrocarbons but also in renewable energy deployment, cross-border grids, and green finance. In Tianjin in 2025, this framework was carried forward as members endorsed an action plan translating the strategy into specific mechanisms for project financing, technical standards, and pilot cross-border infrastructure. In this way, Kazakhstan’s energy agenda was embedded into the SCO’s medium-term program going forward.

Cultural diplomacy was another theme. The “Spiritual Shrines of SCO Countries” project, launched under Kazakhstan’s chairmanship, sought to catalogue and promote shared civilizational heritage. Tokayev also advanced the idea of an “International Coalition on Primary Health Care,” elevating health security into the organization’s remit. These initiatives broadened the SCO’s identity beyond its original security focus, embedding developmental and social policy into its portfolio.

Bilateralism within Multilateralism: Kazakhstan’s Relations with China and Beyond

In Tianjin, Tokayev held extensive talks with Xi Jinping. Both leaders stressed the characterization of China and Kazakhstan as “trustworthy and reliable strategic partners.” Xi identified the bilateral relationship as a cornerstone of SCO cohesion, while Tokayev linked the SCO’s new energy agenda to Kazakhstan’s national strategy for decarbonization.

Kazakhstan’s ambassador to China, Shakhrat Nuryshev, underscored the role of Tianjin’s port and logistics hub as critical for Kazakhstan’s export flows. With its advanced warehousing and maritime access, Tianjin provides Central Asia with a direct outlet to East Asian markets, complementing the overland corridors through Xinjiang. This interconnection of inland and maritime routes illustrates how SCO rhetoric of connectivity translates into tangible economic geography. For example, a significant initiative in this direction has been the development of Kazakhstan’s Aktau Port on the Caspian Sea as a major logistics hub in partnership with the Chinese port of Lianyungang, 600 kilometers south of Tianjin.

The jointly constructed container hub at Aktau, designed to link Chinese maritime and rail infrastructure with Kazakhstan’s growing container transit volumes, brings Chinese investment and operational expertise. A consortium including China Harbor Engineering Company is greatly expanding the port’s processing capacity to establish a “hub-to-hub” transport system connecting China’s coastal ports with Central Asia and further westward to Europe.

Kazakhstan’s role at the Tianjin Summit extended beyond bilateral relations. As outgoing chair, it managed the integration of new SCO members and observers, ensuring consensus within an increasingly heterogeneous bloc. The SCO has expanded rapidly in recent years, now encompassing South Asia and the Middle East alongside its Central Asian core.

The risk of fragmentation is real, yet Kazakhstan’s diplomacy has been credited with maintaining cohesion. Astana’s mediation was decisive, for example, in steering enlargement toward productive outcomes. New members were pressed not merely to observe but to contribute substantively to the Tianjin Declaration. This facilitative style positions Kazakhstan as a broker of governance reform, an unusual role for a mid-sized state surrounded by larger powers.

Analytical Implications

Kazakhstan’s activism within the SCO also affects the internal dynamics of Central Asia. Uzbekistan, under President Mirziyoyev, has also pursued a pragmatic multi-vector policy, but Astana’s ability to set agendas within the SCO gives it greater visibility. Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, preoccupied with domestic challenges, have generally welcomed Kazakhstan’s leadership as a way to channel regional concerns into wider institutions. Turkmenistan, formally outside the SCO, nonetheless cooperates selectively, often through Kazakh mediation.

This regional dimension matters because Central Asia has long risked being overshadowed by the strategic rivalry among China, Russia, and India within the SCO. By inserting Central Asian priorities into summit declarations, Kazakhstan demonstrates that the smaller states are not merely passive participants but can actively shape institutional evolution.

Three themes in particular stand out from Kazakhstan’s role in Tianjin: its agenda-setting capacity, bilateral leverage, and regional brokerage.

First, regarding agenda-setting, Kazakhstan’s proposals on sustainable development, biological security, and investment financing have given the SCO a broader toolkit. Whether all will materialize remains uncertain, but the act of institutionalizing them in summit communiqués is itself an achievement.

Second, Kazakhstan, by anchoring its SCO role in a strong partnership with China, ensures that its initiatives are not marginal. Xi’s public endorsement of Tokayev’s proposals gives them weight among the organization’s members. At the same time, Kazakhstan preserves its multi-vector stance by continuing security cooperation with Russia and cultivating ties with South Asia.

Third, Kazakhstan uses its chairmanships and summit diplomacy to balance the entry of new members and to preserve Central Asia’s collective voice. In doing so, it reduces the risk that the SCO becomes a mere platform for great-power signaling, thereby establishing itself as a regional broker for Central Asia at large.

Kazakhstan as a Eurasian Agenda-Setter

The 2025 Tianjin Summit illustrates the SCO’s dual identity. On the one hand, with Xi, Putin, and Modi projecting their rivalries and partnerships, it was a theater for broader geopolitics. On the other hand, it was simultaneously a forum where Kazakhstan and other mid-sized states succeeded in embedding concrete regional priorities into the long-term strategy of the organization, and therefore also of its larger members.

In particular, Kazakhstan’s proposals link Central Asia’s needs in policy areas like sustainable development, energy transition, and health security to broader debates over global governance. Astana’s bilateral partnership with Beijing provides the leverage to see these proposals through, while Kazakhstan’s regional diplomacy ensures that Central Asia as a whole is not eclipsed.

The interests of the SCO’s diverse members will prevent it from becoming a unified bloc. However, its evolution into a multidimensional forum where security, economics, energy, and culture all have a place owes a good deal to Kazakhstan’s entrepreneurship. The Tianjin Declaration carries the imprint of Astana’s agenda, and its implementation to 2035 will test whether that influence endures.

What emerges most clearly from this perspective on the Tianjin Summit of the SCO is that Kazakhstan is no longer only a participant in Eurasian multilateralism but increasingly an agenda-setter. It uses institutions like the SCO to weave Central Asian priorities into the broader architecture of Eurasia. This role enhances regional agency in a world of shifting power balances, providing a pathway for the translation of Central Asia’s geography into diplomacy, from which follows the latter’s translation into durable influence.