The potential adoption of a law on foreign agents has sparked heated discussions and even serious conflicts in Kazakhstan. However, some experts believe that labeling foreign agents will help the country’s citizens understand whose interests certain sections of the media and bloggers are serving.

Discussions about the possible adoption of a foreign agents law in Kazakhstan have been ongoing for several years. The sharp reduction in USAID activities worldwide, including in Kazakhstan, has given new momentum to the debate. A directive from U.S. President Donald Trump to shut down the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) brought shocking details to light.

It was confirmed that over the years, USAID had spent millions of dollars funding various projects in Kazakhstan. Some of these projects, including those involving the Kazakh government, were related to energy, modernization, healthcare, and other progressive fields. However, a significant portion of the funds went toward media resources that promoted a specific point of view in Kazakhstan, often leading to conflicts, as extensively reported by The Times of Central Asia (TCA) in a series of articles.

Following Trump’s directive, Mazhilis (Parliament) Deputy Magerram Magerramov accused USAID of lobbying for the LGBT community. According to him, Elon Musk and Trump had called USAID a criminal organization. The deputy claimed that foreign-funded non-governmental organizations (NGOs) were promoting an alien and harmful perspective in Kazakhstan.

Sources indicate that the shutdown of USAID’s activities has already led to the closure or suspension of certain media outlets in Kazakhstan and Central Asia. For example, on February 17, Mediazona Central Asia announced it was temporarily ceasing operations.

The issue of foreign funding for media and bloggers has caused an intense reaction in Kazakhstan’s information space. Amid the USAID shuttering, Mazhilis deputy from the People’s Party of Kazakhstan, Irina Smirnova, proposed amending the legislation on foreign financing. Her proposal served to escalate tensions.

On February 12, Smirnova submitted a parliamentary inquiry to Prime Minister Olzhas Bektenov. According to Smirnova, around 200 NGOs in Kazakhstan receive foreign funding, with 70% financed through various U.S. sources. Official government data shows that the country has 165 different grant donors, including 53 international organizations, 31 foreign government organizations, and 81 foreign and Kazakh NGOs.

“Even experts find it difficult to distinguish between friendly resources and those that require caution to avoid falling under the influence of destructive ‘soft’ power,” Smirnova stated, representing this a challenge for Kazakh society.

According to Smirnova, many countries counter such challenges by adopting foreign agent laws. For example, Israel has had such a law since 2016, China since 2017, Australia since 2018, the UK since 2023, and France since 2024. One of the original models for such laws is the U.S. Foreign Agents Registration Act, enacted in 1938 to counter Nazi propaganda.

Smirnova suggested that Kazakhstan should develop national legislation on foreign agents similar to Western countries so that citizens can evaluate and compare information while understanding its source. Her statement triggered a massive backlash, however, with the most extreme reaction coming from Arman Shuraev, a former politician, who seemingly used offensive language toward Smirnova on social media, accusing her of defending a pro-Russian position. Shuraev later deleted the post, claiming his account had been hacked.

Nevertheless, Smirnova stated that she regarded his remarks as an act of ethnic hostility, and publicly requested the Ministry of Internal Affairs to document Shuraev’s attacks and legally assess his actions.

According to Kazakh political scientist and director of the public foundation Kemel Arna, Zamir Karazhanov, Kazakhstan and Central Asia will experience the effects of Donald Trump’s policies. Karazhanov believes it is evident that USAID will either be shut down or completely change its operational format.

“The agency was originally intended to help the populations of developing countries, focusing on clean water, food, education, healthcare, and other humanitarian needs. However, over time, USAID actively engaged in the media sphere, addressing issues that, frankly speaking, concern impoverished populations in developing countries the least. The organization needs to return to its roots, where good intentions were initially laid,” Karazhanov told The Times of Central Asia.

According to Karazhanov, many media outlets in Kazakhstan received support from USAID, and these projects will now inevitably face funding shortfalls.

“Under Trump, this trend will continue for at least four years, his term in office. His statements do not emphasize human rights, freedom of speech, or democracy. Trump is an authoritarian leader at the head of a democratic system,” Karazhanov stated, adding that he believes that during Trump’s presidency, far-right politicians and ideologies will gain momentum worldwide.

Additionally, however, Karazhanov argues that USAID and other Western organizations violated liberal democratic principles by imposing foreign ideas and engaging in mass propaganda. Thus, the concept of Western influence clearly needs reconsideration.

According to Karazhanov, provisions on foreign agents are currently scattered across multiple legislative acts in Kazakhstan. This approach may have been driven by a reluctance to provoke conflict with the West or exacerbate internal disputes, as seen in Russia and Georgia after adopting similar laws.

“We should focus on the interests of Kazakh society. There is no need for excessive restrictions, but the public must be informed about the sources of all information. Whose position does a given media outlet or blogger represent? This is critically important. There is a geopolitical struggle in the world, and Kazakhstan has weak information security. Any foreign state can influence us through its media. It should not be the case that a Kazakhstani channel is covertly promoting the ideology and narratives of a foreign state,” Karazhanov argued.

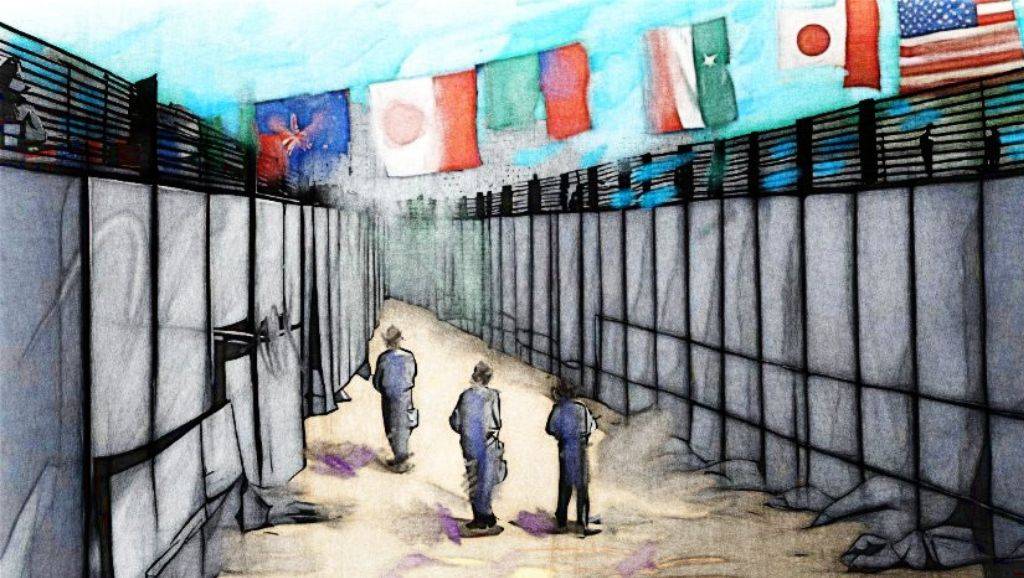

Many democratic Western countries choose to regulate foreign influence on their citizens, including by controlling social media.

“There must be clear and precise definitions, including for the term ‘foreign agent’ itself. If the legal norms are scattered across multiple acts, clarity it’s impossible. Especially with controversial laws like this, ambiguity cannot be allowed. The state’s position must be clearly formulated within a single law,” Karazhanov argues. “If a foreign agents law is adopted, it must apply equally to everyone. The most important distinction is whether the funding source is domestic or foreign. If it is foreign, then the audience must be informed — regardless of how small the foreign funding share is. The sponsoring country does not matter; it can be friendly or unfriendly. The foreign agents’ law should only reflect Kazakhstan’s national interests.”