The Board of Peace and the Emerging C6 Regional Ecosystem

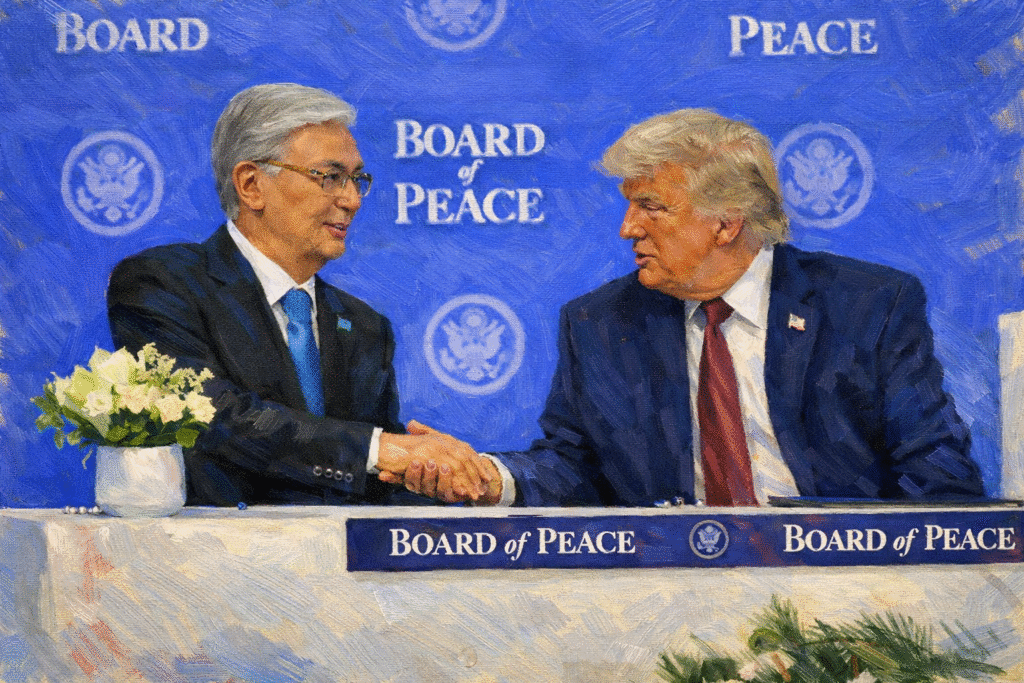

Washington is hosting the first summit of the Board of Peace, an initiative convened by U.S. President Donald Trump. Aircraft carrying leaders from several post-Soviet states have arrived at Joint Base Andrews. While Russia and Belarus have been invited - representation levels vary - the presidents of Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, and Azerbaijan have traveled to the United States in person. Although each leader has a separate bilateral agenda, Kassym-Jomart Tokayev, Shavkat Mirziyoyev, and Ilham Aliyev share a broader objective: presenting a consolidated regional grouping, informally referred to as the C6, in which Kazakhstan is seen as playing a leading role. Tokayev, a career diplomat who previously served as a senior United Nations official, has developed a consistent approach to foreign visits, which typically includes a meeting with Kazakh citizens residing abroad, particularly students and young professionals, and the publication of an opinion piece in a leading outlet in the host country. During his current visit to the United States, he met members of the Kazakh diaspora and published an article in The National Interest outlining his vision for international stability. [caption id="attachment_44160" align="aligncenter" width="2560"] President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev meets with Kazakh citizens living and studying in the United States; image: Akorda.kz[/caption] According to Kazakh political analyst Andrei Chebotarev, the central theme of Tokayev’s article is the importance of stability amid intensifying geopolitical rivalry and growing international conflicts. Chebotarev emphasized Tokayev’s call for a pragmatic international order grounded in the rule of law, accountability, predictable commitments, and respect for national and cultural identities, arguing that ideologically driven frameworks have proven ineffective. Tokayev described the Board of Peace as “not just another forum for endless discussions,” but as a practical initiative aimed at delivering tangible outcomes, particularly in relation to the Gaza Strip and the broader Middle East. He characterized the White House’s approach as one that views peace “not as a slogan, but as a project” built around infrastructure, investment, employment, and long-term stability. “This initiative deserves respect and international attention,” Tokayev said. During his visit to the United States last November for the C5+1 summit, Tokayev held meetings with senior U.S. officials, including Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick, as well as executives from major international corporations. A delegation led by Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of National Economy Serik Zhumangarin is also in Washington during the current visit. In addition to promoting investment and technology partnerships, the delegation engaged with members of Congress involved in efforts to repeal the Jackson-Vanik amendment, which continues to complicate trade relations between the United States and certain Central Asian countries. Mirziyoyev has pursued a similar agenda during his current visit, holding meetings with U.S. Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick and U.S. Trade Representative Jamieson Greer. He also met representatives of American businesses and signed an agreement establishing a new investment platform. [caption id="attachment_44171" align="aligncenter" width="1280"] A set of bilateral agreements on priority areas of Uzbekistan-U.S. cooperation was signed; image: President.uz[/caption] Aliyev, for his part, met in Washington with the leadership of the American Israel Public Affairs Committee, including...