LONDON (TCA) — Upcoming December 4, the Uzbeks will go to the polls to elect a new president, following the death of their quarter-century-ruling leader Islam Karimov. Investors can take a break while those dreaming of a velvet revolution are in for a wake-up call: the issue of “succession” in Uzbekistan appears to have been well-precooked in a most timely and almost elegant manner. As in surrounding former Soviet republics except Kyrgyzstan, the Uzbeks do not like surprises, especially those considered prepared elsewhere.

The expected winner is former Prime Minister and now interim head of state, Shavkat Mirziyoyev. Apart from Mirziyoyev, who represents the Liberal Democratic Party – dubbed Karimov Fan Club and resembling similar parties focused on personalities rather than ideologies, three other candidates have been listed for the race. They are Sarvar Otamuradov on behalf of the Uzbekistan National Revival Democratic Party, Narimon Urmanov of the Justice Social Democratic Party (Adolat), and Khatamjan Ketmanov of the People’s Democratic Party of Uzbekistan. All parties that are submitting a candidate, without any real chance, are actually loyal to the system.

Besides the proposed candidates, three of the most powerful people in Uzbekistan’s political echelons — National Security chief Rustam Inoyatov (nicknamed the Uzbek grey cardinal), finance minister Rustam Azimov, and Senate Speaker Nigmatilla Yuldashev — will not take part in the race. In all: the issue of “power succession” has been well-prepared and the December election will only make it official. In other words: no “Uzbek Spring” in sight…

Depending on standards of living

To the outside world, Mirziyoyev has already sent signals not to be afraid of unexpected trouble. He has once more confirmed Uzbekistan’s commitment to the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, the security and development platform which includes all EEU member states, China and India, and even put the door open to Uzbekistan’s re-entry into the narrower but more proactive security pact CSTO which it left a decade ago and further consists of the EEU states plus Tajikistan. For the time being foreign policy is not on top of Tashkent’s agenda. It is the economy that could either sustain the existing political framework or make it shake on its vestiges depending on the standards of living.

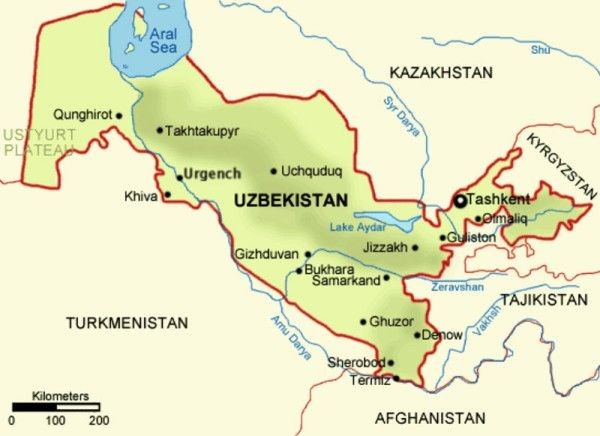

The interim head of state comes from the resource-rich province of Jizzakh, which separates the areas of Tashkent and Samarkand and therefore the notorious rival clans of “Tashkiy” and “Samkiy”, for both of which Mirziyoyev, who belongs to neither of them, may well be accepted as a neutral and thereby reliable candidate. From day one, he has toured the country, handing out commitments to support, including financially, the Uzbek industry, services and infrastructure. They include rehabilitation and expansion of electric power generation and distribution systems, and especially in Tashkent, modernization of the suburbs by building new apartment blocks, raze the random shantytowns and expand the Tashkent underground network to allow swift and affordable transport.

Peace at home, peace in the world

It illustrates the fact that the big challenge for the new head of state and his team is clearly not keeping peace in the world but first and foremost at with as little outside interference as diplomacy necessitates. And the key to peace at home is protection and improvement of the population’s standards of living. Protection and improvement here means amelioration of economic performance without putting existing achievements at risk by pursuing adventurous policies.

In the first half of this year, according to the National Statistics Committee, Uzbekistan’s gross domestic product rose by 7.8 per cent on-year to 89 trillion Uzbek Sum (1 US dollar = approx. 3,000 sum). Industrial output over the period saw a 4.7 per cent rise to UZS 50.9 trillion. It means that GDP is growing twice as fast as productivity – meaning that Uzbekistan is moving away from a production-driven economy in the direction of a consumption-driven one. The Uzbek industry still accounts for more than half of the economy – which is a lot better than can be said of e.g. Kyrgyzstan where it is hardly more than 10 per cent. But even for Uzbekistan the danger of an eventual “consumption bubble” exists and should be taken into account by the government.

Assets and asset value growth

For investors (especially foreign ones), the message could hardly be clearer: you are entitled to make profit, but you do not own the place. China which accounts for over half of Uzbekistan’s external capitalisation has appeared to grasp that message, and limited collateral on investments to output and not to property from an early stage on in Uzbekistan as well as in other Central Asian ex-Soviet republics. Today, both China’s state corporations and its private enterprises maintain this strategy all over the world, including Africa and Latin America. By contrast, quite a number of western investors have shown too little comprehension for the principle – and broken their teeth on it.

As usual, figures confirm words here. Still according to the State Statistics Committee, investments into tangible objects in the first half of this year amounted to just over 22.3 trillion sum, equivalent to $7.8 billion, showing an on-year nominal increase of 11.8 per cent and of 1.7 per cent rise in its share in the national GDP to 26.6 per cent. But only 5.13 trillion, less than a quarter of the lump sum, came from foreign capital resources, while just over half of it, or about 14 trillion, came from domestic private resources, only 2.5 trillion of which was facilitated through loans and/or credit lines.

The good news is that in Uzbekistan the bulk of economic growth is based on asset and asset value growth and a widening gap between assets and liabilities, rather than a break-even ratio or worse which causes debt bubbles ending in massive defaults and money wasted on bailouts. Those “enlightened investors” pursuing fair earnings rather than displaying an outdated “neocolonial” mentality have therefore a good chance to succeed in Uzbekistan, providing they know the rules well and stick to them.