The emergence of AI is considered by many to be a major tectonic shift, much like the emergence of the internet in its time. It is hard to overestimate the role innovation plays in our lives, with founders all over the world trying to pioneer our way out of the next problem. At first glance, the Kyrgyz Republic’s tech sector does not represent anything particularly meaningful. The chances of the small landlocked country – the farthest from any ocean in the world, which is the most affordable mode of shipping mode – integrating into innovative global ecosystems on its own seem wholly unrealistic. However, if we look at the dynamics of development in its tech sector, the potential is there. Is there a chance that the Kyrgyz Republic can become a part of the global tech scene?

Image: The World in Maps

According to Ashley Vance at Bloomberg, “It’s about a landlocked nation, one with very few natural resources, hoping to gen up a tech industry on the fly.” The Kyrgyz startup ecosystem is clearly in its nascent stages, meaning that you haven’t heard about the Kyrgyz Skype. Yet. The country’s position in the Global Innovation Index in 2024 is 99th, up from 106th in 2023. The Global Startup Ecosystem Index, meanwhile, has the Kyrgyz Republic lower than 100th place in its 2024 ranking, down from 99th in 2023. “The country has maintained second position in Central Asia and seventh in the Central Asia Regional Economic Cooperation Program (CAREC) business region,” according to this index.

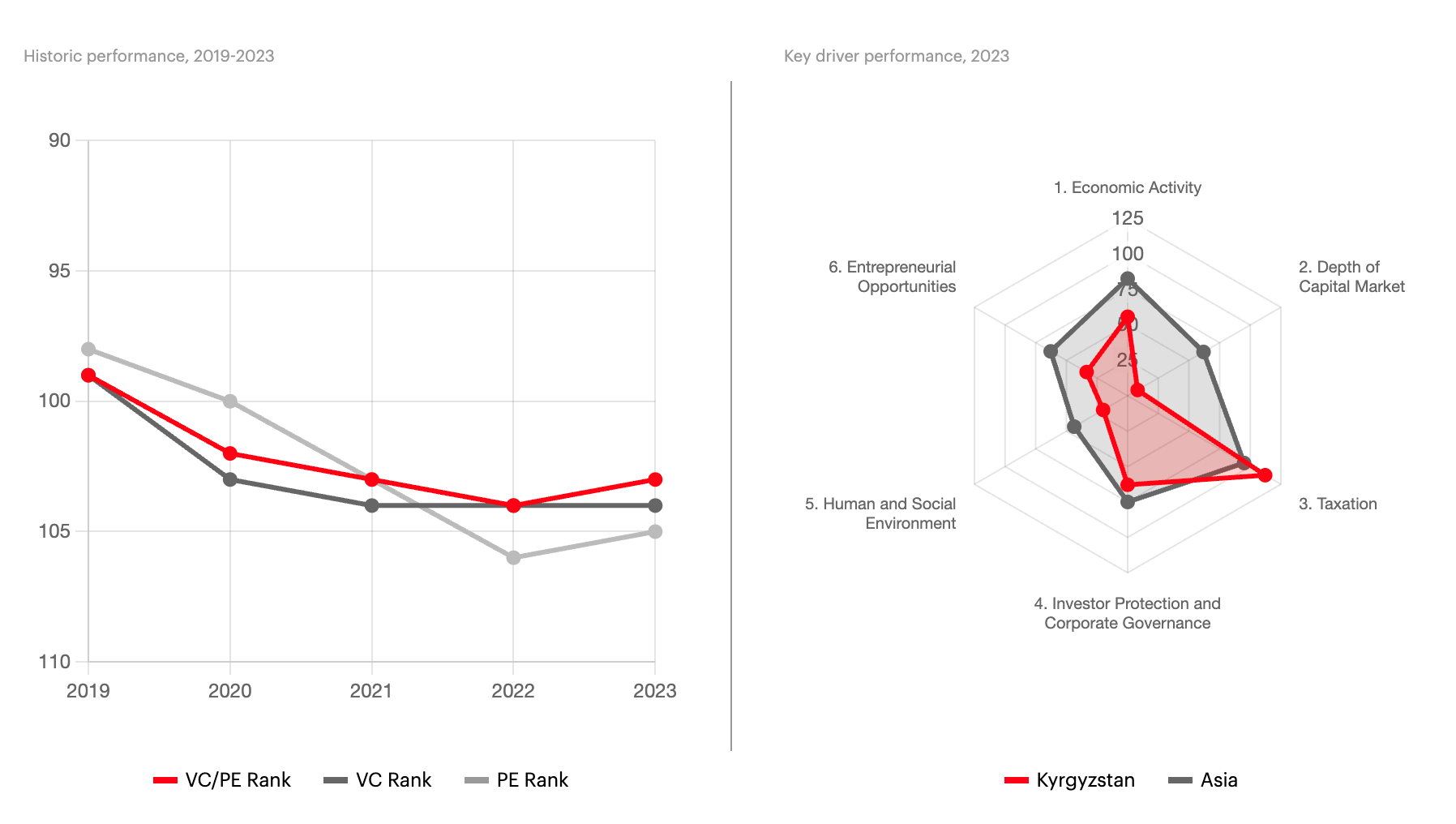

The Kyrgyz Republic’s VC ranking of 103rd in the Venture Capital & Private Equity Country Attractiveness has barely changed over the last couple of years. When compared to peer group economies, it is obvious that the Kyrgyz Republic needs significant improvements in the depth of the capital market, social environment, entrepreneurial opportunities, and economic activity.

Image: Venture Capital & Private Equity Country Attractiveness Index 2023

In terms of the number of venture capital deals, the Kyrgyz Republic is still lagging behind its neighbors. Out of $110+ million of venture capital funding in the region in 2023, the Kyrgyz contribution was only a fraction at $1.1 million. In 2024, this increased to $1.7 million, however, with the country’s first venture capital law soon to be adopted.

Image Venture Capital in Central Asia 2024

The High Technology Park of the Kyrgyz Republic, which is a special tax regime for IT companies targeting exports, is demonstrating a steady growth, with its revenue expanding from under a million in 2013, to a more impressive $130 Million in 2024. The park’s residents are mostly companies providing IT outsourcing for developed markets, but the signs of a turn towards launching their own IT products are there. A separate world-first Creative Industries Park has also been set up to support the country’s creative industries, including startups.

When it comes to the largest Kyrgyz startups, they are founded by Kyrgyz nationals, who have built their startups in more sophisticated ecosystems. Erkin Adylov’s Behavox is an illustrative example of such a story. The company, which is the largest provider of AI-compliance solutions for financial institutions, raised $100 million from SoftBank’s Vision II Fund in 2020. In late 2024, Behavox secured an additional $70 million credit facility from Hercules Capital (NYSE: HTGC) for strategic expansion. A brilliant example of a soonicorn (a startup that is expected to reach the $1 billion unicorn valuation in the near future) can hardly be called a Kyrgyz startup in its full meaning, however, as it is not integrated into the local tech ecosystem.

Another so-called hybrid group is represented by those founders with expertise in more developed ecosystems who have now taken a more active role in the domestic sphere. One such person is Tilek Mamutov, both the first Kyrgyz national to become a software developer at Google and the first admitted to Y Combinator, the leading global startup accelerator based in Silicon Valley. Mamutov’s startup, Outtalent, is helping tech professionals around the world land jobs in the largest global tech companies, such as Meta, Amazon, Apple, Netflix, and Google. Not only is Mamutov helping his customers from different parts of the globe, but he is also contributing to the local startup scene by sharing his expertise. He has even moved his company’s HQ from Silicon Valley to Bishkek.

Finally, the local ecosystem has seen an explosion of locally born stories. If a decade ago the local tech scene was reminiscent of tumbleweeds in the desert, this year alone seven Kyrgyz startups were admitted to top global accelerators: Yessa — Antler Vietnam, Admitted — Antler Malaysia, Chef Vision AI — Antler Vietnam, Core Pod — Launch, MyStory — StartX, BabyGuide — Antler Malaysia, and Neobis — Google for Startups.

Another challenge is that no country in the region can integrate into the global ecosystem alone. Even larger countries in the region, such as Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, are still too small when it comes to the global scale. The optimal opportunity, therefore, is to be found in integrating as a region, and the trend is heading in that direction.

Last year Silicon Valley saw the very first Central Eurasia @ Silicon Valley conference, which took place in the legendary Yerba Buena Arts Center in San Francisco right before TechCrunch Disrupt. The event became the largest representing the region in Silicon Valley to date. It is now clear that regional cooperation represents the best chance of ultimately becoming a part of the global tech scene.

But even with regional integration there is one more challenge to address. Without access to more mature ecosystems, there will be neither the expertise nor the capital. This is why we are seeing innovation hubs opening in different parts of the world that provide a soft-landing for founders from our region, connecting local ecosystems with established ones like Silicon Valley. One such hub is the Silkroad Innovation Hub, which organized the Central Eurasia @ Silicon Valley conference last October. The Eurasian Startup Hub is building a similar bridge in the UK, while the Al-Farabi Innovation Hub is doing the same in Saudi Arabia, and now in Dubai. There are even attempts afoot to build a hub in China.

Whether the Kyrgyz Republic can become a part of the global innovative ecosystem will depend on its ability to foster regional cooperation and to build relationships with more evolved ones as it continues to facilitate a favorable environment for Kyrgyz founders. But the seeds have certainly been planted — and while still in their early stages, their promising trajectory is becoming more and more obvious.