At a moment when Kazakhstan is building new cultural institutions and asking bigger questions about what contemporary art should do, one curator has been quietly learning how power, taste, and narrative are shaped inside major museums. Akmaral Kulbatyrova, the first representative of Kazakhstan to receive the U.S.-based ArtTable Fellowship, spent 2025 working in the Exhibitions and Curatorial Projects Department at The Bass Museum of Art in Miami Beach, gaining rare inside access to how global exhibitions are conceived and positioned. Her work sits at the intersection of institutional practice and cultural repair, focused on reframing nomadic culture, Central Asian heritage, and Kazakh craft not as static tradition but as a current language.

Akmaral’s experience links ambition and execution, showing how local histories can enter international spaces without being flattened. In this interview with The Times of Central Asia, we asked her what comes next.

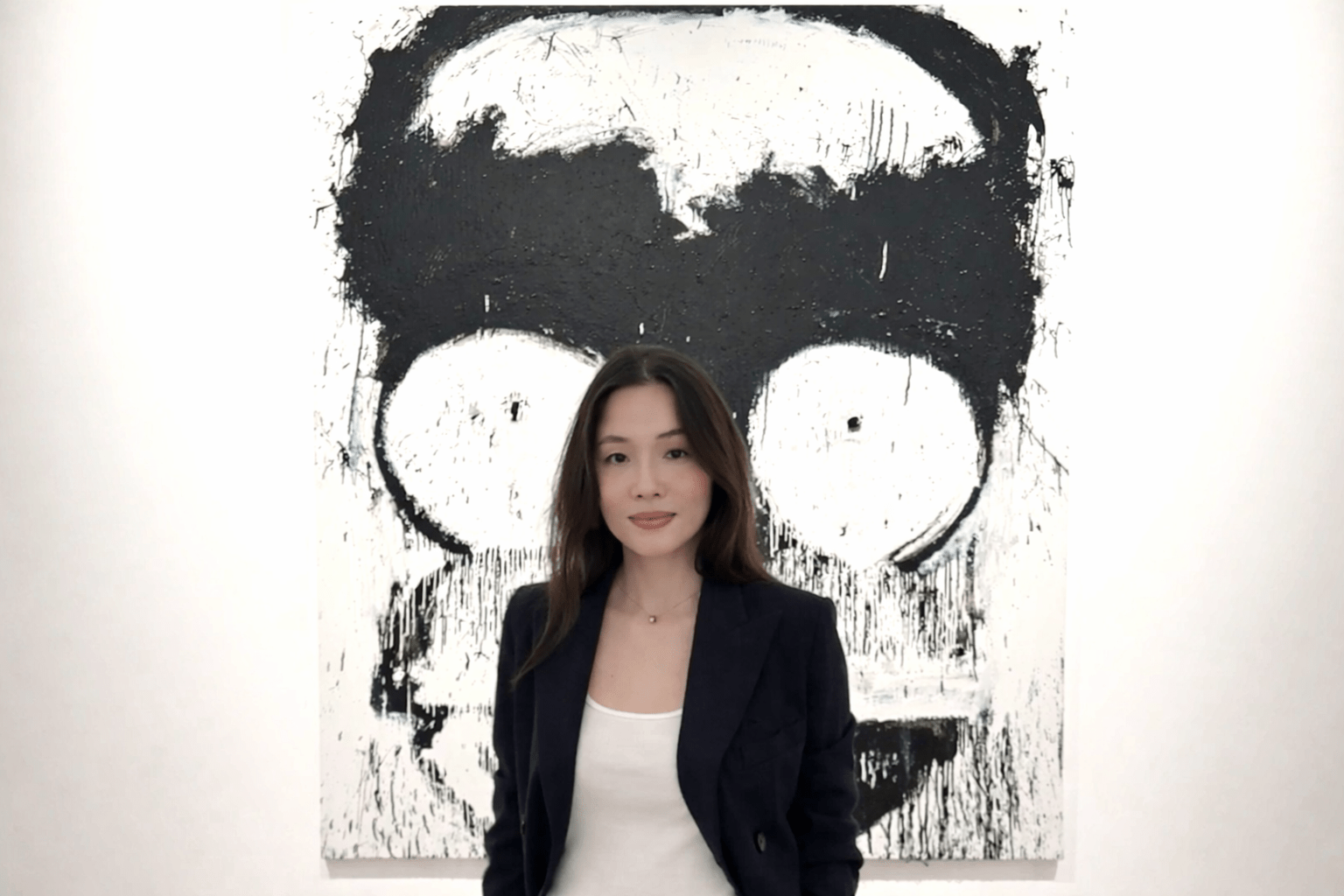

Akmaral Kulbatyrova; image courtesy of the subject

TCA: Nomadic imagery has become central to Kazakhstan’s national identity since independence. How are contemporary artists reshaping these symbols, and why does that matter for how the country sees itself today?

AK: Kazakh contemporary artists briefly challenged Kazakh art in early avant-garde experiments in the 1960s. However, it stopped because of the huge presence of Socialist Realism, which was one of the movements where symbols like horses and yurts prevailed. Most of the contemporary artists reshape not the symbols; they reimagine nomadic culture, contextualizing pre-Soviet culture through researching how it changed over time. Many artists look back to pre-Soviet nomadic practices to explore how these traditions were disrupted by colonial and Soviet policies, yet continue to influence Kazakh identity today. By using installation, performance, and video, they move beyond decoration and folklore to show nomadism as a living culture rather than a museum image or symbols. This matters because it helps Kazakhstan see itself not through simplified national symbols, but as a society shaped by change, cultural mixing, and an ongoing negotiation between past and present.

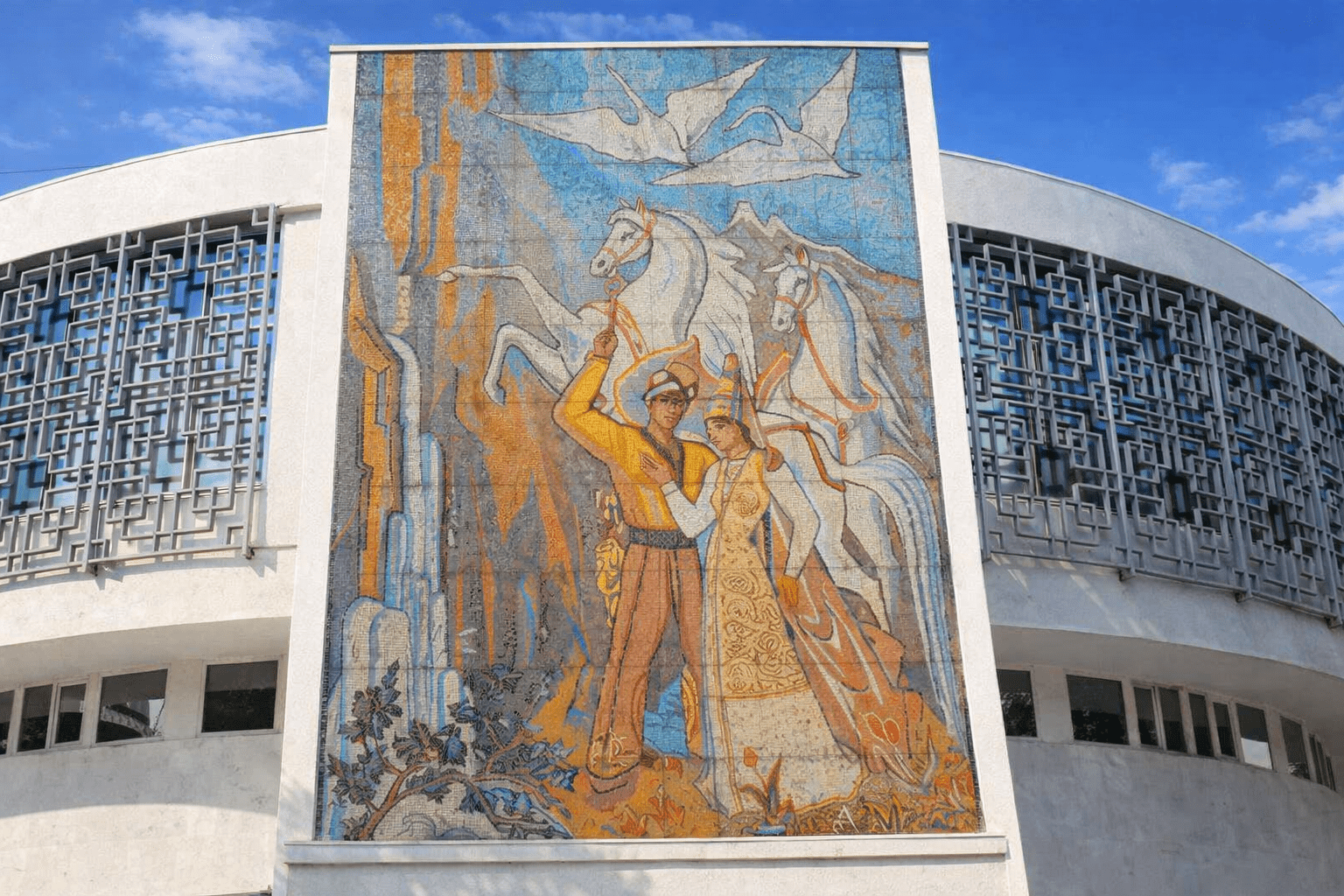

Qyz Zhibek, designed by Nikolai Vladimirovich Tsivchinsky and Moldakhmet Syzdykovich Kenbaev, 1971; image: TCA

TCA: Nomadism now circulates widely in pop culture, often detached from its historical meaning. Why does contemporary art provide a more critical way to examine what nomadic identity represents?

AK: It’s typical that symbolic images prevail in pop culture, especially for countries that have not experienced a long artistic tradition. It is one of the ways to be acknowledged by the privileged cultures through the symbols that are easy to recognize and quickly signal national identity. In Kazakhstan, these images became important after independence, as they cover the main question of cultural uniqueness after colonial influence. Contemporary art takes slower and more contextual approaches rather than easy recognition. That’s why most modern scholars criticize symbolic language and would like to see art that explores unresolved histories and how nations were challenged or used their experience to construct their identity.

Anvar Musrepov, IKEA KZ; image courtesy of the Aspan Gallery

TCA: Many artists use nomadic motifs with irony rather than nostalgia. Why is irony such a powerful tool for rethinking Kazakhstan’s past and present?

AK: When I started thinking about why artists use irony in relation to nomadic imagery, I realized it has a lot to do with distance. Nomadism no longer exists as a lived social reality in Kazakhstan. Kazakhstan is not just a society of nomadic tribes; it is a prosperous and modern country. By using irony, artists begin to question the symbols themselves that should carry a more contextual mode rather than something sacred. It creates a space to separate real historical experience from the images we use to represent it. Irony in nomadism should be a language to understand our past and rethink it, rather than trying to return to or re-enact a way of life that no longer exists.

Dilyara Kaipova, Pushkin; image courtesy of the Aspan Gallery

TCA: Women’s roles in nomadic history are often romanticized or overlooked. How are female artists and curators reclaiming nomadic narratives, and why is this perspective essential to understanding Kazakh identity today?

AK: The presence of women in nomadic history is definitely rare. In most cases, contemporary artists try to show them as passive figures in history. For example, last year in the exhibition named “Beneath the Earth and Above the Clouds” by Sapar Art Gallery, the artworks of Aya Shalkar raise the question of feminism, gender roles, and women’s identity in Kazakh society. Kazakh identity is multi-layered, and these narratives help us to understand that we built our identity not only through conquests and wars, but also through intergenerational knowledge, living practice, and domestic work. These perspectives are essential for understanding the full complexity of the nation’s past and present.

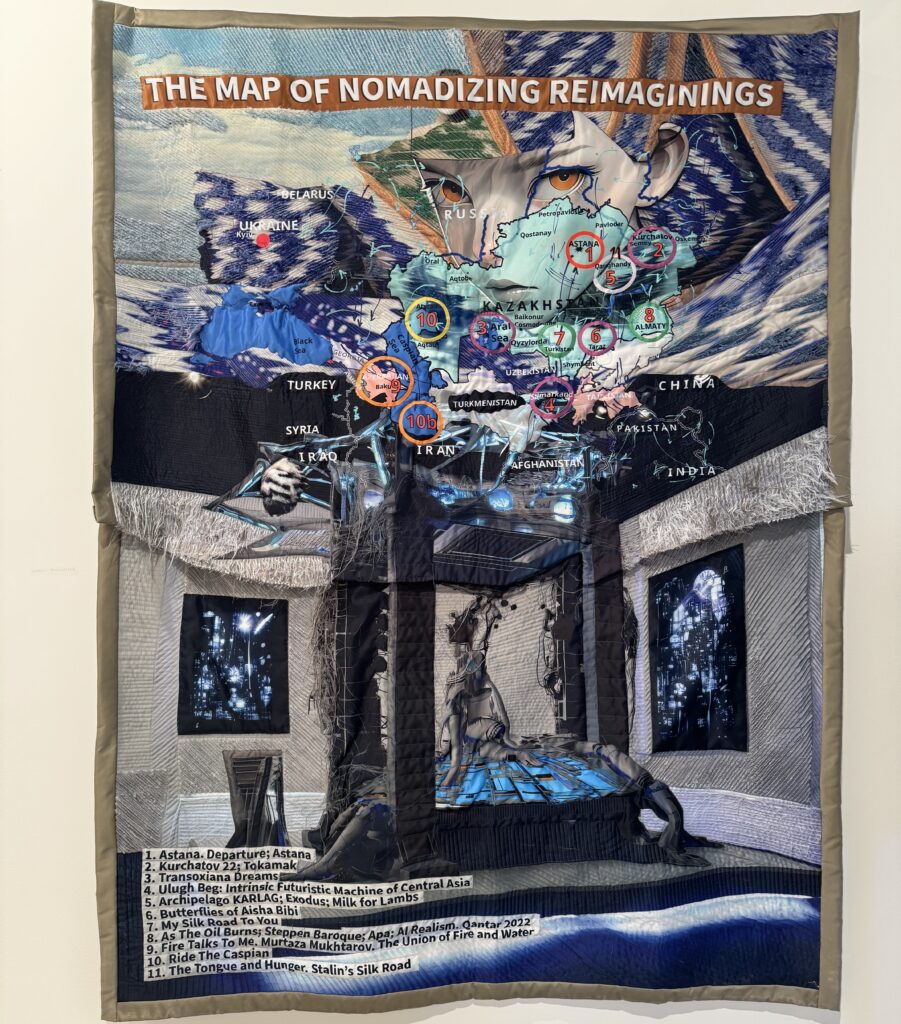

Gulnur Mukazhanova,

Moment of the Present; image courtesy of the Aspan Gallery

TCA: As Kazakh contemporary art gains international visibility, why does it matter how works rooted in nomadic culture are interpreted by global audiences?

AK: Context is important in contemporary art. Kazakh contemporary art is now considered exotic in Western institutions, which leads to some risks of it being represented as stereotypical or decorative. That’s why it is important to include a context that opens a conversation about the complex histories, modernization, and fluid identity of Kazakhs. Most contemporary artists are concerned about being framed properly and clearly, which I think is important to understand Kazakh art not as cultural branding, but as an active participant in contemporary discourse.

TCA: Which modern Kazakh artists have you worked with that are inspiring, and why?

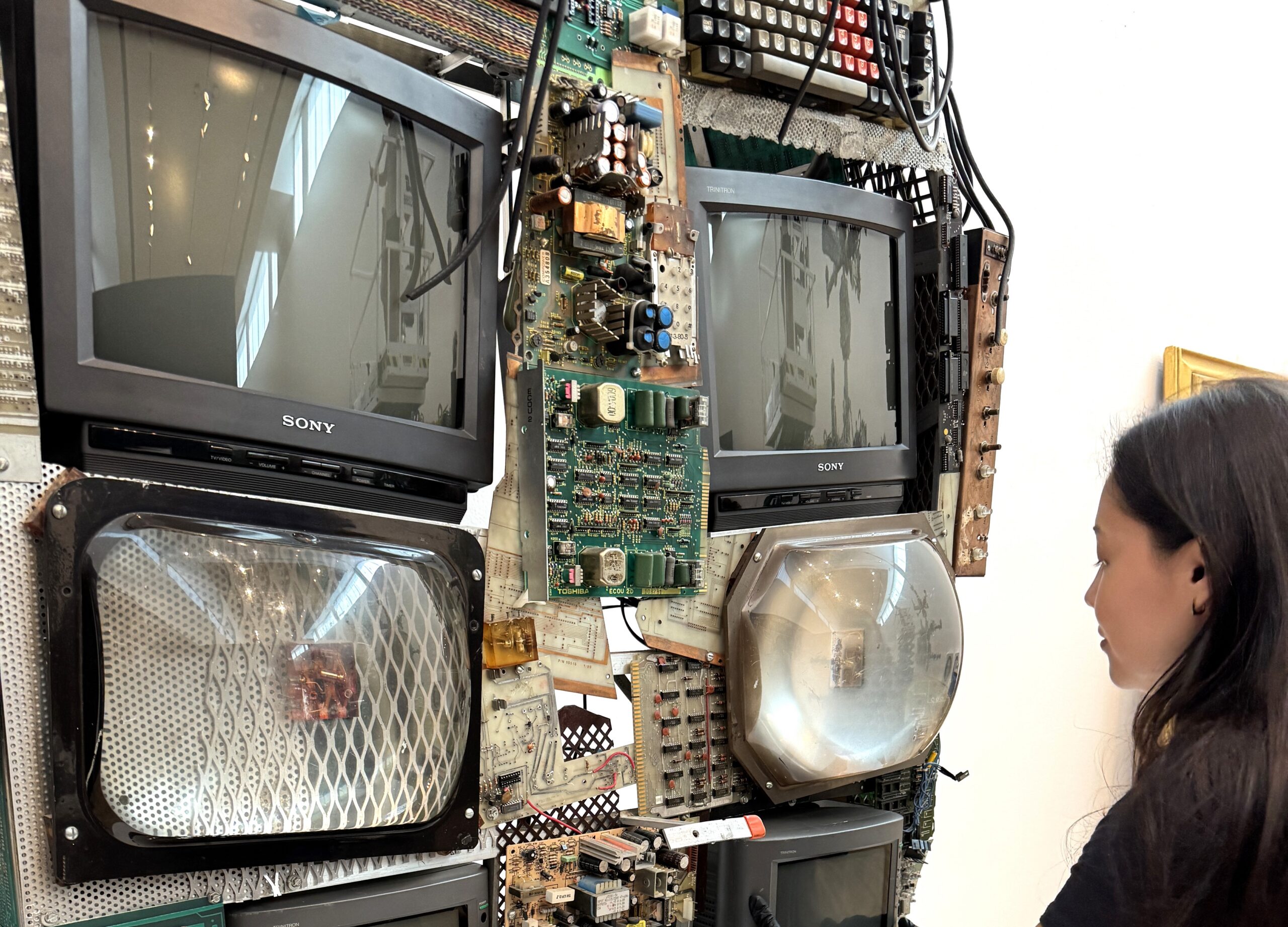

AK: There are contemporary artists in Kazakhstan whom I engage through curatorial research or international exhibitions, and I find them particularly interesting and inspiring. I would like to mention artists in new media arts like Anvar Musrepov and Almagul Menlibayeva, who stand out for their critical exploration of digital space and contemporary forms of nomadism. In textiles, I admire the work of Gulnur Mukazhanova, whose use of traditional materials fuses craft and contemporary conceptual art, and Dilyara Kaipova (Uzbekistan), whose bold textile works critically reframe Uzbek traditions with modern pop culture. These artists are the ones who bridge tradition, history, and innovation, using different mediums to simultaneously speak of local histories and engage in global conversations.

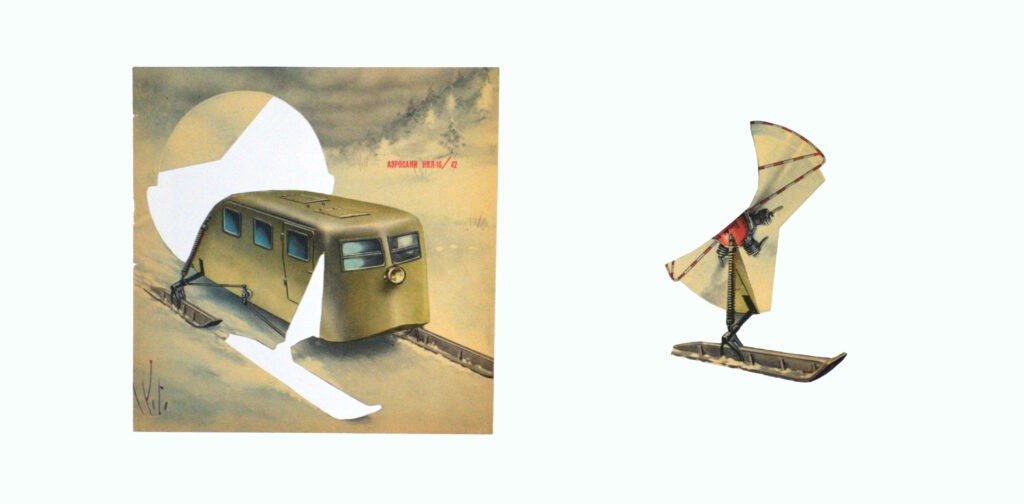

Anvar Musrepov, Jigitovka; image courtesy of the Aspan Gallery

In Kulbatyrova’s telling, nomadism is not a costume to be worn for worldwide consumption, but a critical framework for thinking about history, gender, power, and modernity. What emerges is a vision of Kazakh contemporary art that resists both nostalgia and easy cultural branding. As Kazakhstan steps onto a larger institutional stage, the question is no longer whether its art will be seen, but how it will be read. This conversation makes clear that the stakes are high and that the framework, care, and intellectual rigor will determine whether Kazakh art enters the international discussion as an equal voice or a decorative footnote.