Inspired by TCA’s coverage of the 2024 World Nomad Games and the incredible showcase of falconry events, I reflected on a visit to the Sunkar Entertainment Complex near Almaty, Kazakhstan. Established during the Soviet era, the complex was originally designed as a mountain retreat for workers, featuring saunas, horseback riding, skiing, and other snow sports.

However, its defining feature today is the bird sanctuary founded in the 1990s to conserve the region’s dwindling population of birds of prey. The sanctuary serves as both a conservation effort and an entertainment venue, highlighting the delicate balance between preserving natural heritage and creating an engaging visitor experience.

A practice the beginnings of which are shrouded in mystery, many experts trace the origins of falconry back to the steppes of Mongolia, dating between 4000 and 6000 BCE. Bronze Age cave paintings suggest falconry was already established, and a third millennium BCE pottery shard from Tell Chuera, modern-day Syria, depicts a bird of prey. The oldest visuals of falcons, however, are etched into rocks from the Altai Mountains, spanning Central and East Asia, circa 1000 BCE.

Finding information on falconry in Europe and the Middle East is easy, but uncovering its ties to Kazakhstan’s nomadic traditions proves more challenging. A podcast featuring two generations of a Kazakh family from the Altai Mountains sheds light through oral traditions. This narrative highlights falconry as more than a sport – it’s a historical bond between humans and birds of prey, offering profound insights into nomadic heritage.

Hunting with birds at the World Nomad Games, Astana, 2024; image: TCA, Stephen M. Bland

The Golden Eagle, often called the “Empress of the Sky,” holds a divine status in falconry. Renowned for its ability to stare directly at the sun without harm, it’s a symbol of freedom and pride for the Kazakh people. The Kazakh language boasts a staggering vocabulary for falconry, exceeding 1,500 unique terms. Its importance is also immortalized on Kazakhstan’s national flag, echoing the legacy of Genghis Khan, whose banner also featured an eagle at its center. This speaks to his passion for falconry, a tradition vividly documented by Marco Polo, who described eagle hunting with Khan’s grandson as early as the 1100s.

The bond between humans and birds was so blurred that in ancient times, a nursing mother could share her milk with golden eagle chicks, even when her own child faced food scarcity.

The Siberian golden eagle, or burgut, is among the largest of its kind. The formidable females, favored for hunting, boast wingspans of two meters and talons stretching up to six centimeters. Weighing over six kilograms, these birds demand not just expertise but also exceptional strength and courage from their handlers.

Female eagles are traditionally captured before they learn to fly – old enough to survive outside the nest, but still nest-bound. They’re considered larger and more reliable hunters once tamed compared to their smaller, less-predictable male counterparts.

Breaking eagles is a foundational skill in falconry, requiring meticulous preparation and specific tools. The process starts with an eagle hood, crafted from cowhide, to blindfold the bird except during hunts and feeding, ensuring safety for people and livestock. Falconers also protect themselves with elbow-length leather gauntlets, safeguarding against scratches. Jesses, sturdy leather straps, are secured to the eagle’s legs and fastened to a Y-shaped birch racket, allowing the falconer to control the bird securely on their gloved fist. Whether on the ground or mounted on horseback, each step prioritizes control, precision, and safety.

Eagle training demands endurance, both from the bird and the trainer. Typically, it takes seven to ten days to tame an eagle’s wild spirit, though the most stubborn bird might stretch to two weeks. Any lapse in vigilance, such as allowing the bird to rest for more than ten minutes during critical training, can undo days of work. Through sleep deprivation and constant interaction, a bond of mutual recognition forms. Once this trust is established, the eagle ceases to challenge her trainer and submits to their authority.

Falconers have a saying: In summer, people provide for their eagles; in winter, the eagle provides for them. Summer brings plentiful pastures and herds, ensuring eagles are well-fed. But when the icy grip of winter descends, turning the land barren, the roles are reversed. Eagles hunt foxes, hares, wild cats, and even wolves, delivering both meat and fur. These vital supplies bolster stored resources, ensuring falconers and their families endure the harshest season unscathed.

The relationship between a falconer and their bird is unique — distinct from the bond most Westerners have with their pets. Falcons are not companions; they’re respected partners in a mutual agreement. Many traditional falconers honor this “contract” by keeping their birds for five to ten years before eventually releasing them and allowing them to reclaim the freedom to soar in the skies. With golden eagles living up to 30-40 years, ensuring they spend much of their lifespan in their natural habitat is seen as both just and essential.

Woman with bird of prey, World Nomad Games, Astana, 2024; image: TCA, Stephen M. Bland

Kazakh eagle hunting faced near extinction but has seen a stunning revival since 2000, thanks to Mongolia’s prestigious Golden Eagle Festival. This event not only celebrates the art of eagle falconry but has also cemented its survival and cultural significance within the Mongolian Kazakh community. While historically male-dominated, the sport saw a ground-breaking moment in 2014, when 13-year-old Aisholpan Nurgaiv became the first Mongolian woman to compete at the festival. Her story, a testament to resilience, is powerfully captured in the 2016 documentary The Eagle Huntress. Today, efforts focus not just on sport but also on the preservation of birds of prey, as championed by the International Association for Falconry.

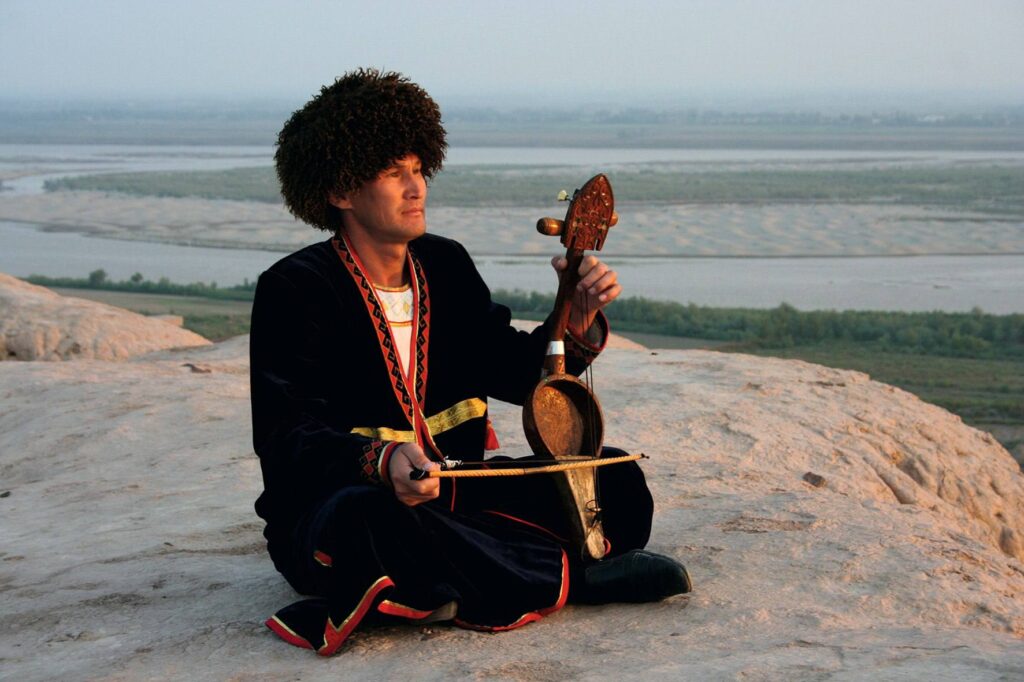

In my experience with these birds of prey, we were a group of international tourists captivated by a breathtaking showcase of avian mastery. Eagles, owls, and vultures demonstrated their remarkable skills under the guidance of an expert trainer. Adding to the spectacle, another trainer, fully adorned in traditional nomadic attire, paraded these majestic birds on his arm while riding horseback. The display showcased remarkable traditions and skill, captivating us as they swooped within inches of our heads.

Displaying a bird of prey on horseback, Sunkar Entertainment Complex, near Almaty; image: TCA, Ola Fiedorczuk

A guided presentation on birds of prey brought an unexpected twist. When asked if anyone in the group was vegetarian, I raised my hand. The guide explained that birds of prey are carnivorous, adding that they “can’t exactly feast on cucumbers.” Perhaps he was gauging how a Western audience would react to such dietary realities.

When he asked for a volunteer to feed the bird, there was silence, no takers. Then, he picked me. The task at hand was presenting this sharp-beaked creature with the leg of a baby chick. Distressing, yes, but my focus was on survival — specifically, keeping all my fingers. I tossed the offering to the bird at lightning speed and yanked my hand back, mission accomplished.

The author with an owl, Sunkar Entertainment Complex, near Almaty

When my duty was done, and I rejoined the fellow Americans in my group, their reactions floored me — disgust and horror all around, and these were meat-eaters. I couldn’t resist pointing out the irony – one even owned a cat – and feeding the bird, I explained, was no different than feeding your pet.

The falcon trainer’s attempt at humor then misfired badly. Pulling out a lifeless mouse to feed the bird — complete with cartoonish-looking X’s marking out its eyes — he made it bounce theatrically while referencing Mickey Mouse. Unimpressed, the crowd met his act with cold glares.

“Tough crowd,” his expression seemed to say.

Despite some inappropriate humor, it was a remarkable and unforgettable adventure. Should you find yourself near Almaty looking for something to do, discover living history with a must-see experience that combines stunning birds of prey with UNESCO intangible cultural heritage.